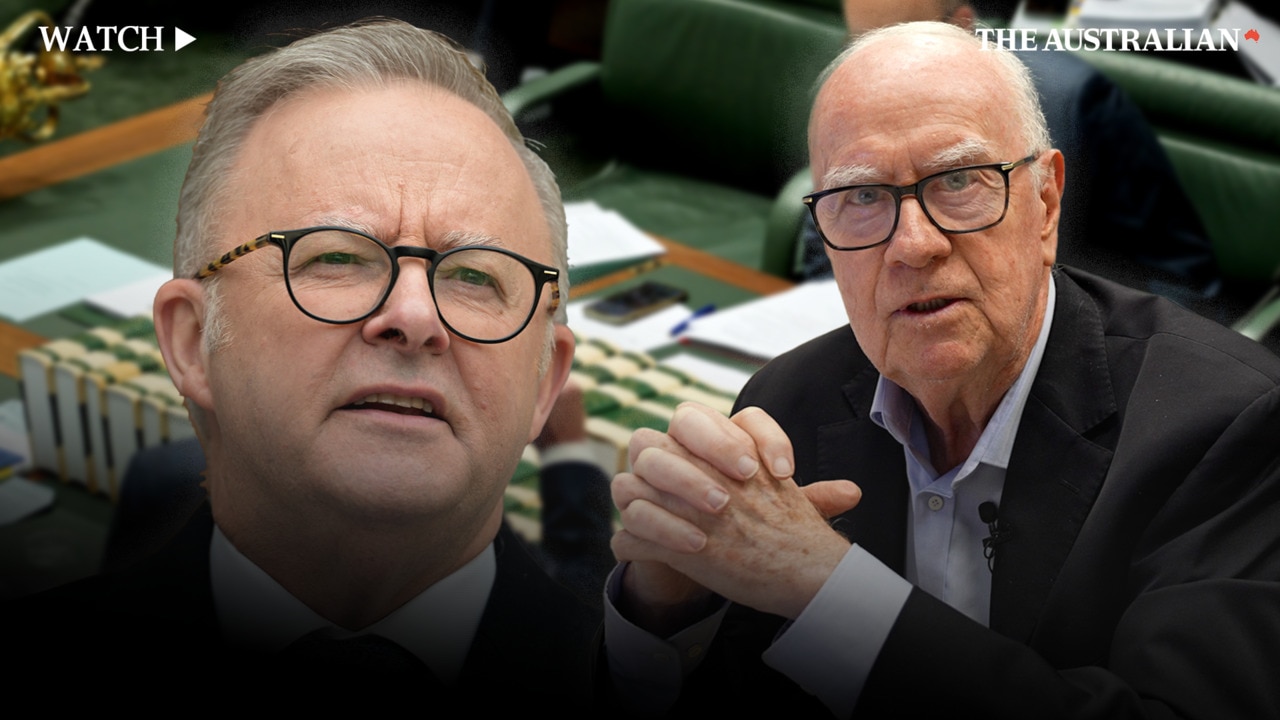

Albanese is a master tactician, but where’s the strategic vision?

Anthony Albanese’s character as a tactical and transactional leader has never been more evident. His biggest problem is incrementalism in an age of transformation.

The shape of the Prime Minister’s 2025 election campaign is on display. The message in uncertain times is “we have your back”. Albanese’s pitch to a doubtful public is “we’re making progress” and “we’re getting things done”. It sounds modest because it is modest. He offers a long list of practical achievements. But the conundrum is obvious: have Labor’s policies actually improved your life?

But Albanese has a fallback. He is awaiting Peter Dutton’s agenda, confident the Coalition vote is soft, that the Opposition Leader’s policies will make him the issue, that the Coalition’s risk of voter breakaways to the right will re-occur and that Labor has the skill to sink its negative teeth through Dutton’s programs.

Albanese’s dilemma lies in his 2022 victory. He won on an agenda of reassurance, not transformation. Remember that ALP national secretary Paul Erickson said the job was to persuade an electorate consumed with fatigue and anxiety to actually make the switch. Albanese campaigned on “safe change” – not “big bang” reformism, not inspirational vision, not sunlit uplands.

Albanese never captured the public’s imagination. There was no charisma, just correction for Bill Shorten’s excesses and destroying Scott Morrison’s character. It was the correct tactic. Labor could scarcely tolerate another defeat, a fourth in succession. The victory was all tactics, little strategy. This is how Albanese has governed.

But reassurance in a world of technological, strategic and economic upheaval doesn’t work. The world of 2025 is far different from the world of 2022. The 2020s are an age of disruption, dislocation and destabilisation, courtesy of Donald Trump, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. Nearly every certitude is under threat. Leaders must lead and smart governments get proactive. Expect vast changes to occur in today’s world in a short time.

Navigating those changes will be hard and Albanese cannot avoid the existential question. What, pray, does the Australian Labor Party stand for in the 2020s? What does it believe? Labor won in 2022 on a program of tactics, not conviction; witness the stage three tax cuts saga.

Looking towards 2025, Albanese as Mr Practical and Mr Caring says “we’ve got your back is our message”. That’s good. But is it enough? Does he radiate conviction? Every sign is that the 2025 election campaign is the next instalment of the 2022 election campaign. That’s more of the same. Indeed, Albanese keeps declaring his aim is to “continue to deliver our agenda”. But let’s face it, progress is modest. The government has been busy but there’s a disconnect between action and outcomes.

Off the back of Labor’s legislated successes in the Senate last week, Albanese and Jim Chalmers have summarised a litany of policy achievements – redesigning the stage three tax cuts, housing support for renters and home buyers, aged-care reforms, expanded childcare, cost-of-living support, manufacturing jobs, the Future Made in Australia scheme, cutting student loan debt, Reserve Bank restructuring, pressure on supermarkets, fee-free TAFE, protecting kids under 16 from Big Tech, subsidising wages in the care economy, production tax credits and competition policy initiatives, among others.

In normal times this list is impressive. But these aren’t normal times. What impact are these policies having? Is the wider public even aware of them? They might be the start of something big. They should be the start of something big. But that’s some time and distance away. At this stage they are incremental change and they are substantially lost in the fog of household recession. A decade of weak productivity compounded by the post-pandemic inflation eruption has trapped Albanese in a nightmare of public frustration.

While Albanese was elected with cost-of-living being the main election issue, inflation has proved more lethal and prolonged than Labor anticipated.

Recent analyses published by The Australian and The Australian Financial Review cast our living standards in an even more alarming light – showing the worst decline since the 1950s, with the fall in real disposable incomes greater than in the past four recessions and disposable incomes now 2 per cent lower than pre-pandemic, the sharpest decline among OECD nations.

This suggests a special Australian failure. The blame is collective, on both Coalition and Labor. There is now mounting evidence that the retreat from economic reform under the last six prime ministers – an Australian malaise – is being visited upon Labor with a vengeance. And this raises vital questions for the country. Is Albanese Labor even on the right course? And how does “having your back” work in an age of transformation?

Albanese functions as a tactical operative. One of his most astute moves was to seize the Dutton position of banning social media for under-16s and make this his own – a popular step that challenges Big Tech but is opposed by the Greens and many progressives. He has retreated this year from any crackdown on gambling ads in the teeth of powerful vested interests; and he has vetoed Tanya Plibersek’s deal with the Greens to legislate Nature Positive environmental law reforms, to bolster Labor’s seats in the West – the state that made him Prime Minister at the last election. There is no philosophical or ideological pattern here. It is purely tactical politics.

He gives ministers significant autonomy but the problem is a lack of strategic direction and co-ordination from the centre. Albanese had one try at being a transformational leader – the Indigenous voice – and its defeat drove him back on to the road of caution. He is prepared to innovate – the social media ban for adolescents being an example – but retail politics define the limits of his innovation. He doesn’t like risks. He doesn’t believe in Gough Whitlam’s “crash or crash through” and doesn’t act out Paul Keating’s axiom that “good policy is good politics”. He became Prime Minister by rejecting Shorten’s ambitious tax redistribution agenda and knows Julia Gillard lost on her prized carbon tax.

Albanese’s problem is incrementalism in an age of transformation. The danger is looking weak in the face of sweeping challenges. Yet the trade-offs are hard. The public wants strong leadership but is divided over the type of leadership. The times demand bold policy but bold policy comes with greater electoral risks.

This is not just an Albanese problem; it is a problem for Dutton. It is a problem for Australia. We need transformational policies but the politics are too dangerous. Both leaders know this.

Albanese functions under three constraints – the budget is heading back into prolonged deficit; his leadership is defined largely by policies yet to significantly improve household life; and his margin is razor thin. He functions as a prisoner of the politics that made him Prime Minister – his recent response under the pressure of declining opinion polls was to double down, not to change course. He has no electoral buffer for the inevitable next election anti-government swing.

Whitlam’s nine-seat majority meant he survived the 1974 election swing; Bob Hawke’s 25-seat majority meant he survived the 1984 election swing; Kevin Rudd’s 18-seat majority was enough for Gillard to scrape into minority government in 2010. But Albanese, with 78 out of 151 seats, enjoys no such cushion. The normal anti-government swing at the second election consigns Albanese to minority government.

If Labor has a transformational policy it is 82 per cent renewables by 2030, with high power prices and massive rollout problems eroding public support just as high inflation has weakening the electorate’s commitment to climate change as a priority. Yet the Coalition, despite its nuclear pledge, has yet to explain how it will deliver cheap power, let alone lower inflation, a strong economy and better living standards.

Anthony Albanese’s character as a tactical and transactional leader has never been more evident. His current guise is Mr Practical. He is here to help you. Albanese can’t transform your life – but he wants to convince you there are rays of sunshine.