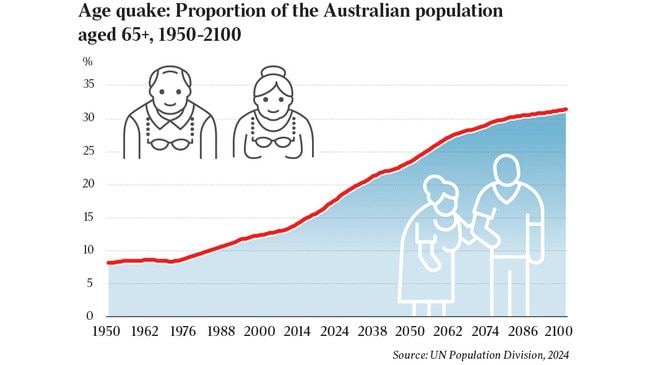

It is a line chart that cuts to the core of our way of life. It is the demographic world’s north star. It is both a best estimate and a projection of the proportion of the Australia population aged 65+ every year between 1950 and the year 2100.

The UN Population Division publishes projections of the population of 195 countries every two years including, most recently, April 2024. This forward-looking dataset includes five-year cohort projections every year to the end of the century.

Indeed, the UN’s population databases by country extend back to 1950. The projections show Australia rising from 27 million in 2024 to 38 million in 2100.

This database provides a unique perspective on the Australian timeline: we can see actual (or best estimates) over 74 years from 1950 to 2024, and projections over 76 years from 2024 to 2100.

Based on this dataset, the number of Australians aged 65+ has increased from 668,000 in 1950, to 4.691 million in 2024, and is projected to rise to 11.953 million in 2100.

More importantly, the projections show that the proportion of the population aged 65+ is estimated to have increased from eight per cent in 1950 to 18 per cent today and is projected to rise to 31 per cent by the end of the century.

Most people today in the decision-making stage of their careers, say, the 40s, 50s or 60s, were born, raised and educated in an Australia (or elsewhere) where less than 10 per cent of the population comprised those beyond the working years, i.e. 65-plus.

Sure, some older workers today are choosing to remain in the workforce beyond the age of 65, but this is not the majority. And especially since the pandemic, when many workers are likely to have had some kind of revelation about their goals in life’s later years. After all, “life’s too short” is a refrain often quoted by those announcing their retirement.

Of course the increase in the proportion of the population aged 65+ has resulted from vast improvements in life expectancy. In 1950, the average Australian (at birth) lived for 69 years (average for men and women) whereas today the average is closer to 84. Life expectancy has increased by 15 years in the last 74 years.

There have been adjustments to social welfare reflecting this (happy) trend towards longevity. In 1950, and indeed since 1908, Australians have had access to an age pension at 65 for men and from 60 for women.

More recently, access to the age pension has been steadily pushed out to 67 and, given the number and the proportion of the population surviving well beyond the pension kick-in age, it is likely to push out even further later in the 21st century. Australia’s pension-age access is generally consistent with pension ages in other developed countries.

Today, about five million Australians are aged 65 and older, and many could reasonably expect to live well into their 80s; while some will make it into their 90s.

An Australia with 18 per cent of the population aged 65-plus is a vastly different world to an Australia with eight per cent are 65-plus. For example, the pension kick-in age equalises for men and women and it pushes out. The level of taxation increases to cover the cost of wellness and healthcare, which rise later in life.

The 65-plus cohort fizzes and fuses into a social group and perhaps even a into political force that is ever anxious to protect rights and benefits. After all, this group isn’t just five million older Australians, this is five million older voting Australians in a nation of 17 million voters.

As a social group, older Australians include those who choose to remain in the workforce as well as others who volunteer, who mind grandchildren, who offer unpaid care often to a family member such as a spouse with mobility issues. Others in retirement take up hobbies or study or become activists determined to bequeath a better world to those they leave behind. Some sing in church choirs.

Here is a world and a life force that did not exist (in quantum) in 1950, when workers might have expected to die after a period of illness soon after leaving work. No need for a retirement destination like the Gold Coast in 1950 as it’d be a poor return on investment for someone retiring at 65 and then dying four to five years later.

Today, however, there’s a third stage of life to be lived and loved in lifestyle destinations popping up all around Australia dominated by established retirees and by a new band of up-and-coming, younger, lifestylers aged 55–64. These lifestylers include couples whose kids have left home, who have the ability to continue to work perhaps a few days per week, and who are looking for activities like fishing, walking, bowling, boating and hosting family get-togethers.

We are the first generation in human history that is tasked with the (surely happy) challenge of developing a business model that collects funds and distributes care and quality of life to those one fifth – heading towards one third of the population – who lives beyond the official working years.

Previous post-work generations (aged 65-plus) were modest in number and lived barely a decade or so beyond life’s working years. And, back then, their various accommodations, including their family homes, were channelled back into the housing market, providing opportunities for the next generation of buyers in their 30s and 40s.

The trend towards human longevity militates against this trend. A greater proportion of residential housing stock (including families’ forever homes) is tied up by a rising proportion of the population aged 65-plus and who could live 20–30 years beyond 65.

The solution of course is to provide attractive pathways for older Australians to choose to downsize to accommodation that better suits an older couple or an older single person’s lifestyle.

And of course with 18 per cent of the total population, and likely an even higher (and rising) proportion of total housing stock now owned by Australians aged 65-plus, there’s (proportionately) less housing stock returning to the market than was the case a generation (or two) ago.

At some point in the future, however, there must come a time when longer-living post-work retirees die and the housing market is then flooded with, to be blunt, executor’s auctions.

Our line chart constructed from the databases of the UN’s Population Division tells the story, the powerful story.

There is no let-up; ageing will continue.

Evermore, Australians will tumble out of this working life and into the lifestyle years, the retirement years, the reflective years.

The adjustment that is needed to reduce the squeeze on housing is for the number of older retiree Australians dying (in their 80s) to exceed the number of family-orientated Australians (in their late-30s early-40s) competing to buy a forever home. That shift isn’t likely to impact the property market until the late-2030s and maybe even the early-2040s as baby boomers die off en masse.

In the second half of the 21st century, Sydney and Melbourne will approach the nine-million mark. The 65-plus cohort will be double the number it was in 2024. Life expectancy in Australia could well be somewhere in the 90s.

Access to the age pension might start in the mid-70s. There will be more segments to the Australian life cycle. The 55-plus cohort could be more nuanced and broken into something like the lifestylers 55–64, the active retirees 65–78, the wind-downers 79–88, and the frail elderlies (surely, the ‘frelderlies’) 89+.

To offer the range of care services expected of a first-world nation like Australia later this century, there is likely to be a wide program of taxation implemented to meet expectations. And there will need to be a vastly bigger healthcare and aged-care workforce, most likely comprised of immigrant workers.

In a macro planning sense, the UN’s line chart shows that there will need to be a better balance between the number of young people coming through and the number of older Australians dying.

What we are going through at the moment is perhaps a 30-year transition period where the number of forever home buyers (in their late-30s early-40s) far exceeds the number of lifestyle home sellers (in their late-60s, early-70s).

Australia beyond the middle of this century will be a bigger, an older, a more highly (or efficiently) taxed nation, comprised of an eclectic and older workforce. And with the baby boomer bulge gradually subsiding from life’s later decades from the 2040s onwards, the housing market will be surely awash with forever homes that are finally passed on to the next generation of young families.

All this and more is evident, I think, from a simple line chart that tracks the Australian community over 150 years from 1950 to 2100.

Bernard Salt is founder and executive director of The Demographics Group; data by data scientist Hari Hara Priya Kannan

It may be a simple line chart, but it tells a powerful story. It is the story of Australia’s past, present and future. It speaks to the issue of housing. It foretells of awkward discussions with Middle Australia and others about matters like taxation.