After 30 years of stagnation and governments adopting a head-in-the-sand approach, the path to reform and action on the 148 recommendations outlined in the final report of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety will take longer than five years to deliver.

Since the 2018-19 budget, $5.5bn has been allocated to support more than 83,000 additional homecare packages, designed to keep Australians in their homes for longer.

While the sentiment is noble, without faster processing times and more carers being trained or available, the at-home care option is not closing the gap quickly enough.

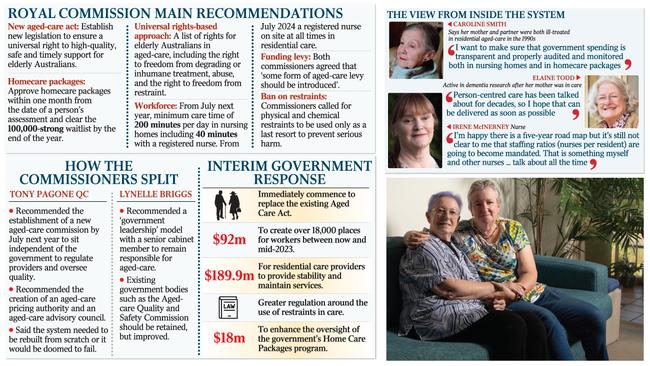

The final report, which includes recommendations to streamline the homecare process and train more carers, says as at June 30 last year 102,081 older people were “waiting for a package”.

“When they do eventually get access to care at home, older people may receive less care than they need, or they may not have access to specific services they need,” the report says.

Expanding and rebuilding the aged-care workforce, across specialist health professionals, cleaners, nurses, cooks and carers, is not possible to achieve overnight. Without better pay and an aggressive focus on training and upskilling, the aged-care system will struggle to deliver for older Australians in cities and regions.

This challenge, raised repeatedly by the Health Services Union and aged-care groups, is highlighted in the royal commission’s final report after years of dithering by governments and private operators.

Scott Morrison addressed this on Monday, making the point that “we cannot just take people off the street and put them into people’s homes and ask them to start caring for people”.

“That would be irresponsible. If someone is going to go into someone’s home or go into the room … in a residential aged-care facility, we cannot compromise on the standards that should be there for those workers to be able to provide that support.”

There are practical measures that can be pursued immediately to support carers. The Prime Minister is open to a recommendation suggesting that by December next year the government considers an additional entitlement to unpaid carer’s leave, similar to maternity leave.

The cost to fix the broken aged-care system will not come cheap, with some in the sector claiming an extra $20bn a year is required.

The royal commission has presented an aged-care levy option to raise funds — a suggestion not typically palatable to Coalition governments.

The HSU, which has threatened to wage a grassroots marginal seat campaign targeting the Coalition and Labor if they fail to reach bipartisan agreements to fix aged care, last year suggested the Medicare levy be increased to inject between $2bn and $20bn into the sector.

Commissioner Lynelle Briggs said the government should introduce by July 1, 2023, an aged-care improvement levy, based on the Medicare levy, of a flat rate of 1 per cent of taxable personal income.

Commissioner Tony Pagone suggested the Productivity Commission urgently consider the “benefits and risks” of an aged-care levy.

Mr Morrison said it was not his government’s disposition to increase levies and taxes. Despite the budget facing a COVID-19 induced $1bn debt pile, the government will pursue funding envelope options to increase spending across the sector dramatically.

The May 11 budget is D-Day for the government’s five-year plan to repair the aged-care system.

The initial $452m response announced on Monday, in addition to the $1bn package announced in the mid-year budget update last December, will be dwarfed by announcements in Josh Frydenberg’s budget.

A blank cheque and 100,000 more homecare packages will not fix the broken aged-care system.