The idea the prince of Wales would become governor-general was recycled for almost a decade from 1974 onwards and had a range of champions including Sir John Kerr, Sir Ninian Stephen, Malcolm Fraser as prime minister and, notably in his earlier years, Charles himself.

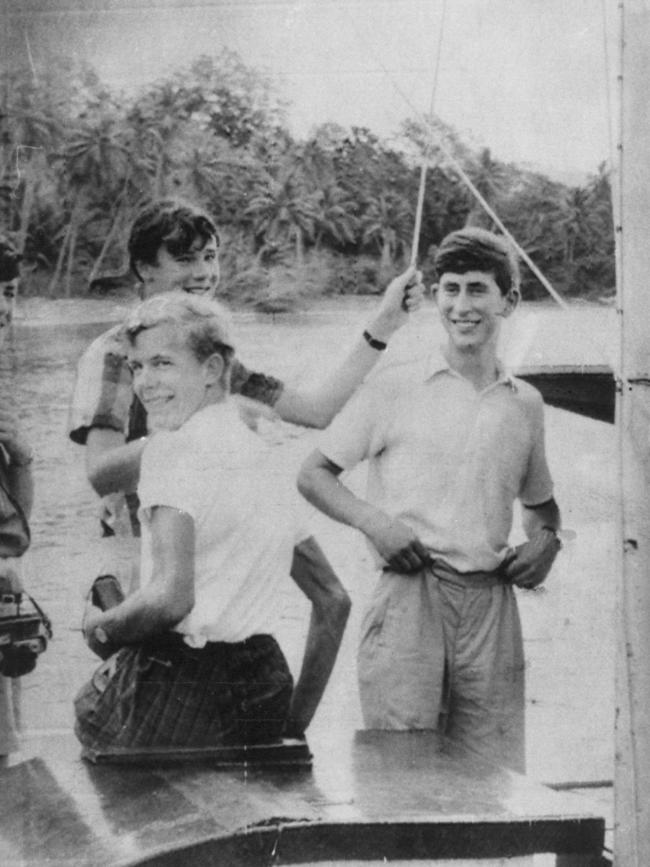

The legacy of his six months at Geelong Grammar, Timbertop, in 1966 shaped the young prince’s attitude towards Australia and left him feeling it was a threshold experience.

“I’d never really gone away from home till I came here,” Charles told me in a 1994 interview. “What it did was help me to know more about myself and also how to talk to people.

“I literally had to sink or swim out here and in the end I began to swim.

“It was, in fact, the best part of my education – the part I enjoyed most, and I have very happy memories of it.”

In subsequent years many Australians aspired to personal bonds with the prince and few tried harder than governor-general, Kerr. Cynics might say Kerr exploited the young man, though Charles never said that. Kerr cultivated the palace and the prince – these were linked but separate domains. Charles had no role as a Buckingham Palace adviser to the Queen on Australian constitutional or political matters.

On becoming governor-general Kerr inherited a project that had occupied his predecessor, Sir Paul Hasluck – the acquisition of a rural property for the prince of Wales. As a young official in the Prime Minister’s Department in 1970, I had perused extensive correspondence on the interest of the royals in an Australian property.

Kerr became an enthusiast for the cause. During the visit by Charles to Australia in 1974 the proposal took tangible form. In the book I co-authored with Troy Bramston in 2020, The Truth of the Palace Letters, we devoted a chapter to the relationship between Kerr and Charles, drawing heavily on Kerr’s papers.

Kerr said Charles had a “very great desire to have a property in Australia” and inspected Yammatree, south of Cootamundra in NSW. At the prince’s request Kerr organised for Charles to raise the issue with Gough Whitlam before dinner one evening.

The prime minister was supportive but said the government wouldn’t provide any funds. Kerr spent much time assisting Charles on financial arrangements. But the hardheads – the Queen and her palace secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, would never indulge the prince.

They felt the property might send the wrong signals about his priorities. Charteris told Kerr “in modern times it was never ‘a good moment’ for the royal family to spend money”, but given economic pressures in Britain there could hardly be a worse moment. Charles was thwarted but felt Kerr had been his steadfast backer.

“I don’t know what I would have done without your help,” he wrote to Kerr.

But there was a far bigger issue involved – the office of governor-general.

“This was something very dear to his heart,” Kerr wrote. “He undoubtedly hoped that some day he could occupy the office of Governor-General.”

Kerr told Charles he would co-operate and was ready to stand aside to allow the prince to assume the office in what would become a decisive move in his career.

Kerr said Charles felt being governor-general was good training for being king. Kerr discussed the issue several times with the prince’s private secretary, Squadron Leader David Checketts. During 1974 and 1975 the office was discussed virtually every time Kerr and Charles met.

Kerr did not inform the palace about these talks. He cherished them, saw them as deeply personal, almost a prize, his business, not the business of Buckingham Palace.

Before the 1975 crisis erupted Kerr, during a meeting in Papua New Guinea, confided in Charles his deepest fears – that Whitlam might seek his recall during a constitutional crisis if there was alarm the reserve powers might be used.

The three relevant points to this meeting were: Kerr did not ask Charles to intervene if his recall subsequently became an issue; Kerr always knew the prime minister had the constitutional power to remove him; and Kerr did not tell Charles of any intention to dismiss Whitlam.

After the dismissal they met in Britain in January 1976 where they reviewed the dramatic events of the previous year in Australia and Kerr again assured Charles he was ready as governor-general to “move aside as we had previously discussed”.

This had a brief potential because the new prime minister, Fraser, flirted with the idea of Charles as governor-general before recognising it was untenable.

The hardheads – the Queen and Charteris – were never persuaded. In August 1976 Charteris killed off the idea, telling Kerr the Queen wouldn’t accept Charles moving to Australia until he was married and settled and added, in effect, the post-dismissal temperature was far too hot. An obvious conclusion.

On March 27, 1976, while at sea with the Royal Navy, Charles made a serious mistake – in a handwritten note filled with sympathy for Kerr, who was struggling against constant demonstrations, Charles wrote of the dismissal of the Whitlam government: “What you did last year was right and the courageous thing to do – and most Australians seemed to endorse your decision.”

Charles went where the Queen never went.

Revealing this note, Bramston and I wrote: “It is a personal letter and Charles is not writing with the authority of the Queen. But this is an unwise letter from the heir to the throne … this revelation has the potential to damage his future as King of Australia.”

Kerr cherished the letter. Many will hold this letter against Charles forever because he endorsed, in private, Whitlam’s dismissal. It was a blunder but a misstep on his road to constitutional maturity, a process that had a further chapter involving Australia.

In the mid-1980s when visiting Britain, the governor-general at the time, Stephen, raised with the prince the possibility of him succeeding Stephen in the office. Charles, older and wiser, said: “It’s very kind of you to think I might conceivably do this.”

Revealing this offer to me during our 1994 interview, Charles said he told Stephen he could do it only on one condition – there had to be “unanimous political support and I knew perfectly well there’re wouldn’t be”.

He was still attracted to the idea, but he knew it could never happen.

How should we see these events?

In context they reveal Australia’s role in the growth and development of the future King – his dealings with our governors-general, politicians, his property dreams and observation of the dismissal from the sidelines – must collectively have played some role in his getting of wisdom, now put to the ultimate test.

The ties and dreams of King Charles III as a young man about serving Australia, acquiring property here and living in this country – now in the distant past – must still inform his thinking and the realistic limits on the sovereign’s dealings with Australia.