It has often been the case that we think a new technology will destroy or transform everything, yet it never seems to happen.

As a species we’ve long had a fear that something will destroy us. For a couple of centuries we’ve worried we might destroy ourselves.

More than two centuries ago, Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, the first great novel about AI gone wrong. Frankenstein refuses to create a female companion for his creature in case they breed and destroy humanity.

Way back in 1966, the greatest of the science fiction writers, Robert Heinlein, in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, depicted a computer becoming self-aware and taking a hand in politics. But the High Optional, Logical, Multi-Evaluating Supervisors Mark IV, or HOLMES IV, as the computer was known, was benign, assisting a libertarian revolt in a tyrannical lunar colony.

Once the revolt succeeds, HOLMES IV resumes a wise, though enigmatic, silence. (That’s very hard to imagine today, for computer or human. Voluntary silence is anathema in our relentlessly babbling culture.)

Since the invention of atomic weapons, we’ve had the physical capacity to destroy ourselves as the human race. But we ought to remember that almost all technology has improved the physical welfare of human beings.

Even nuclear weapons have prevented world war since 1945. Genetic modification of crops is often demonised, but partly because of this we can now reliably feed eight billion people.

When I was born (a long time ago) Australians lived into their mid-60s if they were lucky. Now they average 83. On present trends the average will be beyond 90 in a few years.

AI has all kinds of upsides in increasing productivity and helping to solve problems, especially medical problems. So far, though, it’s not clear that AI really is intelligence. Most of it is brute computing power at speed.

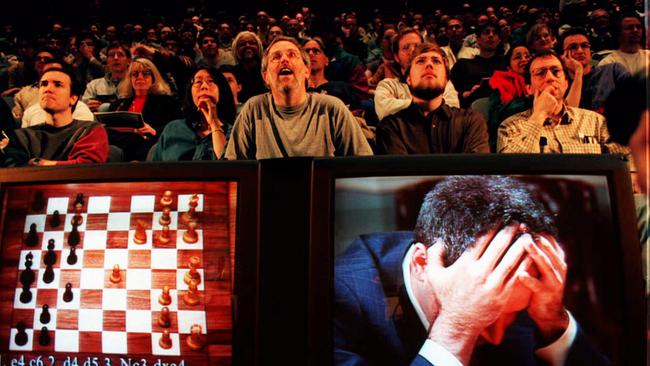

As a young man I was a keen competitive chess player. I was shocked when computers first beat human champions. But chess is a finite game. Though the variations are in the billions, it’s not infinite.

Computers could beat humans decades ago simply by checking which of all the possible moves in any situation most often led to victory. The computer did a bit more than this, but that was the heart of it.

AI is strikingly clever, but most of that cleverness is sheer massive computing power rather than actual reasoning.

It’s still not clear that AI will ever actually achieve general intelligence – that is, the ability to reason. It’s absolutely clear it will be able to behave as though it can reason by emulating what reasoning beings did in similar circumstances.

In a sense AI is like an infinite film archive that not only can retrieve but also can copy and adapt the appropriate bit of footage for any situation it’s presented with. That’s not exactly the same as reasoning.

The normal science fiction way for AI to destroy humanity is that it becomes not only self-aware but also self-willing and much more clever than we are.

We are then unable to discern or decisively influence its purposes, which may one day be to destroy humanity. Pretty unlikely, you’d have to think.

More prosaically, we might instruct it to restore the environment and end global warming and it could then decide, logically enough, that the most efficient way to end global warming is to end human beings. I’ve always been worried about green fanatics. Green computer-age fanatics enabled by AI – lentil terrorists with algorithms – are a frightening prospect.

More seriously, AI might democratise destructiveness.

Remember the internet was going to change everything by making all human knowledge in history available to all human beings online at all times.

It turned out that almost all human beings had almost no interest in all human knowledge. They wanted the net for porn, video games and gambling, and later to exchange gossip and abuse on social media.

Indeed, the saddest consequence of the net for young people has been spending far too long relating to their screens rather than to flesh-and-blood human beings.

There is overwhelming evidence that the longer a young person spends online, they more likely they are to be depressed and lonely.

The serious security concern from the net was that it would enable terrorists by making available to them the technical knowledge required to make chemical, biological, radiological or even nuclear weapons.

Our worst fears have not been realised for two reasons. Nation-states, even paranoid dictatorships, so far don’t want to use such weapons because the retaliation would be devastating.

Even more important, the net has enabled intelligence and police agencies to monitor extremists and to monitor any folks who look up on the net how to make a nuclear bomb.

AI will probably make the threat of random groups of the ideologically extreme, the personally dysfunctional and the dangerously bored more likely to access seriously dangerous stuff.

You could ask AI what you would get your character to do if you were writing a novel about a criminal who decided he wanted to … supply your own horror scenario.

Two final thoughts. AI is all about the technical mastery of language. Language is the key not only to communication but to understanding, thinking and creating.

This confirms the deepest religious insights in our tradition. In the Book of Genesis in the Old Testament God creates the universe by speaking it into being. And at the beginning of his Gospel, John writes: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

Hopefully, AI will lead us to ponder again, more deeply, what it is to be a human being. Being able to destroy humanity wouldn’t make AI human, any more than nuclear weapons are human.

The very best way to study humanity and think about the human condition doesn’t involve AI at all. Rather, it’s through a classical liberal arts education focusing on the Great Books of our civilisation.

That’s where the deepest, most integrated, most profound thinking about what it means to be human – across literature, history, philosophy and, yes, theology – is to be found.

The best technical education preparation for AI would be to study English grammar, for grammar allows you not only to construct language but to analyse it and understand it much better.

There’s nothing artificial about the intelligence in great books and great grammar, but they’ll help you deal with AI, whatever it brings.

More Coverage

Will artificial intelligence destroy humanity? Not if we can muster some natural intelligence.