Murdoch University’s school of education study: school is failing our youth

A study asks young people what they think of school, with surprising results.

There could be worse places to live than Bountiful Bay. Blessed with natural beauty and an abundance of natural resources, the fast-growing region, on the outskirts of a big city, has a sound economy based on tourism, agriculture, mining, manufacturing and service industries.

But while many locals prosper, there are those who do not, struggling on the margins with unemployment, social disengagement and the many associated stresses.

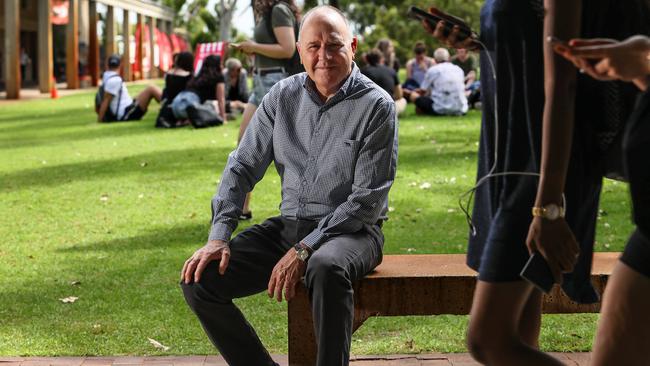

The name “Bountiful Bay” may be made up but the place is real. It’s where a team of researchers, led by Barry Down of Murdoch University’s school of education in Perth, spent 18 months tracking the experiences of 32 young people as they navigated their senior schooling and transition into further study and the workforce.

What they found makes for troubling reading. According to Down, there is a significant divide between what policymakers think young people need to make it in the world of work, and what young people, particularly those who have struggled to remain engaged in mainstream schooling, have come to expect. “Far too many young people are leaving school early or without the knowledge, skills and capabilities to take the next step in life,” the professor says. “This is a major concern for students themselves, their families, communities and governments at all levels.”

Backed by an Australia Research Council grant, the project has become the subject of a new book, Rethinking School-to Work Transitions in Australia: Young People Have Something to Say, co-authored by Down, Murdoch University colleague Janean Robinson and John Smyth, of the University of Huddersfield in Britain.

The book comes as policymakers continue to grapple with youth unemployment, which has remained stubbornly high since the global financial crisis a decade ago. The jobs landscape also has changed dramatically.

Long gone are the days when a single profession could sustain an individual’s working life, with research by the Foundation for Young Australians suggesting today’s 15-year-old is likely to navigate 17 employers in five careers across their life.

A federal inquiry looking at how young people are supported from school and into work has received more than 80 submissions from interested parties who have recommended a raft of measures such as improving career advice in schools, boosting youth employment services and strengthening literacy and numeracy education for young people.

The students who took part in Down’s research were aged 14 to 19, came from a range of ethnic backgrounds, and attended a mix of government and non-government schools. All were considered to be from disadvantaged backgrounds — many from families that were struggling financially — and most had aspirations to go on to university or TAFE, despite their struggles.

“One of the consistent messages we were getting was that for a lot of these young people, school just hasn’t been relevant in terms of the curriculum that was being offered to them and their future aspirations,” Down says.

“There seems to be this inflexibility, and rigidity of rules and regulations, which for many students leads to boredom.”

Down says the research revealed that many students were being streamed into vocational education and training pathways early in their schooling, in some cases before they’d even completed primary school. Many reported feeling frustrated by this but also unaware of how they could challenge it, he says.

The book tells the story of Adrian (not his real name), a student who concedes he is far from being a model student. “I’m a bit lazy and I haven’t handed my work in on time.” He initially undertook a TAFE construction course at his high school because he thought it would better equip him for getting a job than pursuing an academic path.

But after a disappointing work experience stint, he requested to switch to a media studies course.

“I was told the timetable and course issues don’t allow me this choice,” he told researchers.

The school, however, had failed to tap into Adrian’s interests and circumstances in a bid to better engage him in his studies, including that he had been working in a supermarket at night to save money to buy a camera.

Another student reported her experience of ending up in her school’s “special education” program, telling the researchers: “I don’t know how I even got here.”

Down says students who took part in the study overwhelmingly reported needing significantly more support in preparing for life after school than they were receiving. Many floundered afterwards because they struggled with money, transport, dealing with government agencies such as Centrelink, and navigating other educational institutions.

Down believes blaming young people for their disengagement and high unemployment is counter-productive; that the issues are complex and often, such as the economy, out of their hands.

“If we want to develop policy that’s going to work we have to take young people’s points of view more seriously. They are our key informants,” he says. “Young people are telling us that they want to think about their futures, that they want careers, that they don’t want school to be just about passing tests. They want to be prepared for life after school but they don’t feel equipped.”

The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Employment Education and Training is yet to hand down its report from the school-to-work transition inquiry.