Why your investments this year will hinge on these economic signals

There are key features in the investment outlook that should be closely watched this year.

Among my favourites are these:

“When you are up to your ears in alligators, it is difficult to remember the reason you’re there is to drain the swamp.”

“Nothing will ever be attempted if all possible objections must be first overcome.”

“There are known knowns, things we know that we know; and there are known unknowns, things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns, things we do not know we don’t know.”

These unknown unknowns — which I call X-factors and others label as black swan events — frequently rock investment markets. Investors must always allow for, and cope with, the many uncertainties and surprises that affect investment markets.

So, let’s move to the more familiar territory of Rumsfeld’s known unknowns. Here’s a summary list of key influences that investors might like to keep under close watch this year.

• For our economy, there is the monetary and budget policies in the US and, particularly;

• In China, we must watch the effects of the coronavirus outbreak, along with the lagged effects of 2019 cuts in our cash rate and taxes.

• For shares, the direction of the US sharemarket will be crucial.

• For our cash rate, we will monitor the RBA’s views on inflation and unemployment.

• For bond yields, we watch US bond yields; our inflation; and our cash rate.

• For the Australian dollar, there are the key variables of commodity prices, interest rate differentials and the current account surplus.

Let’s dig a little deeper on these key themes: economic growth in Australia slowed in 2019, as households used tax cuts and lower interest rates to retire debt rather than to increase spending. Employment rose, but underemployment remained high relative to the US. Commodity prices remained strong thanks to China’s growth.

It’s too early to assess the effects on economic conditions here from the widespread bushfires in Australia and the coronavirus outbreak in China.

Investors should keep watch on expectations for China’s growth and on the lagged effects that could follow the 2019 Australian tax cuts and falls in interest rates.

Separately, if the Reserve Bank delivers further cuts in its cash rate that participants in investment markets have demanded, the boost could be felt on house prices rather than on spending and jobs.

But the government has been moving its budget into surplus to prepare for “a rainy day” (which, ironically, has come in the form of drought and bushfires). It is well-placed to provide a fiscal stimulus this year.

As I mentioned earlier, the direction taken by US shares is by far the most powerful influence on the Australian sharemarket.

Currently, the consensus view is US shares will deliver positive but modest returns this year: the risk of an early US recession is seen as low and the Fed seems unlikely to raise its cash rate in 2020.

But were wage increases in the US to accelerate (say, to 4 per cent or more), yields on US government bonds could spike and average share prices decline.

Also, major downgrades in US growth could cause US shares to fall sharply. And the US election — particularly if the choice is of a divisive incumbent versus a high-taxing challenger — could rattle sharemarkets.

Share investors may also need to prepare for false crises as sentiment sours and then quickly rebounds (think back to early 2016 and late 2019). Bear markets in shares always begin with a sell-off, but not every sharemarket sell-off is followed by a bear market.

The RBA has made it clear that it would like to see higher employment and a little more inflation. Until recently, market participants were pricing in two further cuts in the cash rate (along with, perhaps, the introduction of unorthodox monetary measures), but the RBA suggests our economy is experiencing a mild recovery.

Around the world, bond yields are extremely low, thanks to slow growth, low inflation and, most importantly, highly accommodative monetary policies. For a couple of years, our bond yields have been lower than those in the US. A marked and sustained increase in bond yields seems unlikely during the next 12 months, but occasional bumps should be expected.

Given low-running yields, investors may have to face losses on their medium-dated and longer-dated bonds. As already mentioned, the best early-warning sign could be a quickening in US wages growth.

For a long time, the dominant influence on the Australian dollar has been the outlook for commodity prices. However, the spread between our rates and those in the US is also important.

The dollar has a history of taking sharp falls when the outlook for global growth (especially growth in China) is downgraded in market thinking or when expectations build up that our interest rates will fall relative to US rates. It then picks up slowly as the global economic outlook strengthens.

The current account in our balance of payments has improved structurally over recent years, and that should reduce the big swings we’ve traditionally seen in our exchange rate.

But old ideas and responses in investment markets can take a long time to dissolve and disappear — a point that investors may need to allow for as they consider the investment outlook for 2020.

Don Stammer is an adviser to Stanford Brown Financial Advisers. The views expressed are his alone.

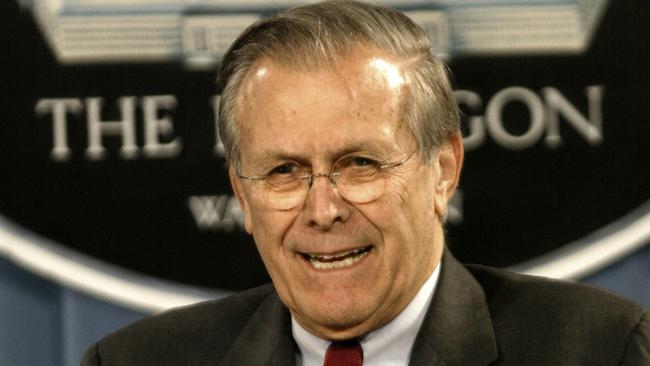

Donald Rumsfeld, a former US secretary for defence, is famous for his apt comments on the challenges for national security — for business and investors.