Xi’s China slowdown has helped slash the price of oil by 30 per cent from this year’s peak and gives hope that inflation can be brought under control without extreme measures from central banks and governments.

In Australia, while we will suffer from lower gas and iron ore export revenue, the oil price slump will curb the inflationary boost set to be triggered when the government’s fuel excise reduction comes to an end.

Last night as oil was falling below the $US90 ($133) a barrel level, a smiling head of emerging market debt and currency at Amundi London, Sergeï Strigo told me that the consequent improved global inflation outlook for 2023 should create increased demand for emerging market debt which has been battered in bond markets this year.

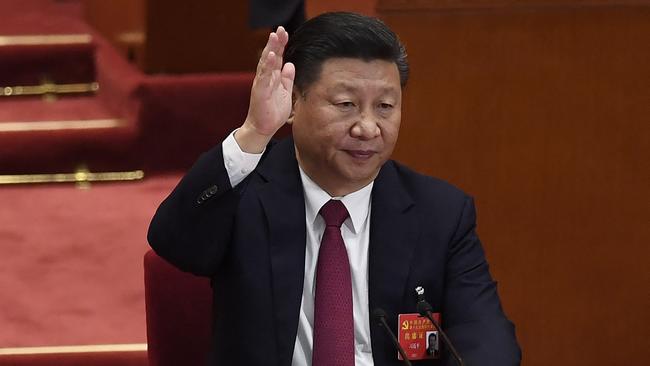

Of course, it was never Xi’s intention to slow down China to such an extent that he would assist western global central bankers and governments in curbing inflation.

The China slowdown was created by the combination of three powerful forces. First, Chinese vaccines against Covid-19 have been much less effective than those developed in Western countries, so Xi has been forced to continue widespread shutdowns to avoid over running China’s health system.

This has come at the same time as deep problems in China’s property and banking system, plus a drought. China has instituted stimulatory measures which overtime will curb the slow-down, but for non commodity exporters, the China slowdown couldn’t have come at a better time.

Of course, OPEC oil exporters are horrified and some are concerned that the oil market has been the subject of a shorting raid by a group of global traders. But there is an additional downward force that is hard to measure. Europe is taking the pain of lower oil and gas usage and that oil and gas supply is secretly being dumped by Russia on other markets which is adding to the downward pressure and exciting the shorters.

OPEC is responding by reducing production but, for the moment, the fall in demand created by China and the other forces have changed the game.

Nevertheless, the severe shortages of gas in Europe, given that Russia has turned off the tap, will force higher interest rates and almost certainly bring on a European recession. But the lower oil price gives hope.

Europe has for a long time been living under the dangerous cloud of negative interest rates. One of the consequences of the Russian gas bans is that European interest rates are returning to sustainable levels, albeit causing staggering losses to the institutions who played the negative interest rate game.

Strigo tells me that in emerging markets most Eastern European countries have bonds yielding near, but below the 10 per cent level, but Hungary is around 15 per cent. Such high rates have not been seen for many years. Ukraine bonds are selling at 20c in the dollar.

Meanwhile, the dumping of US bonds has eased in response to the lower oil and other commodity prices.

There is still an enormous task facing central bankers and governments to bring inflation under control, but the lower oil price provides the first significant green shoot.

Here in Australia, new Treasurer Jim Charmers has grasped the fact that if the government embarks on the spending spree that was envisaged during the election campaign, it will force interest rates even higher. Accordingly, in the October budget, it looks like we are going to see a far more restrained spending policy.

But the unions are in full flight seeking wage rises of five per cent and more and often trying to lock them in to future years They are already preparing for pattern industry bargaining.

Australian chief executives are inexperienced in handling this sort of pressure.

Central bankers around the world are this week privately thanking Chinese President Xi Jinping.