Why 3D printing is making a comeback

After a slow start, fast agile 3D printing is back on track.

–

–

As an anaesthetist, Luis Gallur never dreamt of becoming an automotive parts manufacturer. As a keen historic motorcycle racing enthusiast however, his obsession with restoring bikes introduced him to an entirely different world. Looking for a way to make lighter parts for his race bikes, Gallur investigated 3D printing (also known as additive manufacturing) a few years ago. At that time though he couldn’t justify the price of an industrial-quality machine. But when he was offered the chance to purchase 70 historic 1970s minibikes at a price too good to refuse, the need to source or create replacement parts tipped the economics in favour of 3D printing.

“If you went down the investment path of reproducing these parts using traditional techniques, you’d be looking at $100,000s to buy the equipment,” Gallur says. “The one device can make multiple objects, whereas other technologies are not nearly as flexible.”

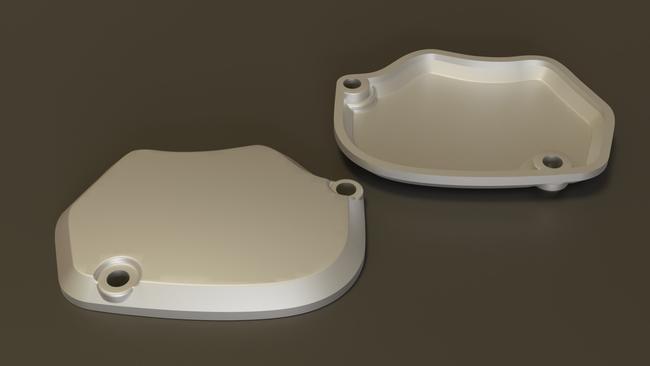

Gallur purchased a high-end Markforged printer from Konica Minolta and began printing chain covers and other parts. He also let various historic motorcycle enthusiast groups know what he was up to.

“I let their Facebook groups know I could create parts and got an immediate response from people wanting to buy 10 of this and 10 of that,” Gallur says. “I was able to determine ahead of time that there was an international market, so I’ve started manufacturing parts in Australia and have sold all around the world.

“Now people are contacting me to ask if I can make other parts. The advantage of additive manufacturing means I can take a part to a CAD drawer who can draw me an STL file, and then I can plug that into the printer.”

Stories like Gallur’s are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the potential for additive manufacturing processes, a market which the research firm Wohler’s estimates will be worth $US15.8 billion this year and will hit $35.6 billion in 2024.

While the technology has been available for some time, several factors are accelerating its uptake. “There is now a groundswell towards using it for end-user manufacturing,” says Matthew Hunter, the innovation product marketing manager at Konica Minolta Australia. “And that has come from there being a lot of development into the materials that you can 3D print with.”

In the past there had been problems with the photopolymers commonly used in 3D printers being not as strong as traditional manufactured plastics and likely to degrade with exposure to UV light.

“But a massive amount of development into the materials you can print with means it has broadened the application set that people can use it for,” Hunter says.

The improvements in materials have been of benefit to Gallur and his emerging motorcycle parts business, including the ability to weave carbon fibre into the nylon substrate, which creates equivalency with metal parts.

“I am now able to manufacture incredibly strong parts — I’ve built parts you can stand on, they are so strong,” Gallur says. “And with additive manufacturing I can have the parts in days, ready to install.”

Hunter says declines in the cost of printers and the materials they use has also boosted uptake, and this in turn has altered the economics for short-run or highly customised production.

“If you are manufacturing hundreds of thousands of the same part you are probably going to use a traditional manufacturing process because it is cheaper,” Hunter says. “But if you are manufacturing a thousand parts, it becomes cheaper to manufacture using additive manufacturing processes, if you can get the material properties you need.”

The speed, cost, strength and versatility of 3D-printed parts has also led to their adoption in the medical sector. For orthotics services company Korthotics, 3D printing has proven exceptionally well suited for producing customised splints and other physiotherapy, orthotic and ambulatory aids.

“Traditionally we would do plaster casting, which was done by hand,” says Victor Phan, a clinical orthotist at Korthotics. “It was very labour intensive and skill intensive, and took a lot of training. What we have found with the adoption of 3D printing and related technologies we have been able to bridge the gap.”

Korthotics is also using a Konica Minolta device, and Phan says he has been impressed with the strength of the parts it produces.

“Kids and adults are putting heaps of weight and stress loads in multiple places through these devices,” Phan says. “They are jumping and walking on them, and doing thousands of steps every day, and need to last for years. So we needed a product that was really reliable.”

Korthotics’ managing director and head orthotist Merrick Smith says patients have also benefited from the speed with which 3D-printed parts can be produced.

“We can have parts for 14 or 18 patients and print in one batch,” Smith says. “And there is no way you could produce for that many patients going through castings and modification and cut-outs and clean ups.”

That in turn is reducing the time taken to produce a device from several weeks to just one. An additional benefit comes through reducing the trauma for the patient, as the procedure of modelling 3D-printed devices is less hands-on.

“We are just scanning and modelling, and then going straight to print,” Smith says.

Hunter says the uptake of 3D printing is also being boosted by people within the manufacturing sector who are accustomed with what the process can produce.

“These devices are being used in schools, so kids moving into the workforce have a very different take on how they might design a part,” Hunter says. “Instead of being constrained by traditional manufacturing they are asking what they can design using 3D printing, and whether they can design the perfect part.”

John Croft is one member of the manufacturing community with extensive knowledge of what the technology can do, having brought the first machine into the country for a private business in 1993 at a cost of a $250,000. Now he is the Additive Manufacturing Hub manager at the Australian Manufacturing Technology Institute Limited (AMTIL), and is engaged actively within the industry to explore its potential.

“Our goal is to provide an industry-driven collaborative network bringing together additive manufacturing technology users, suppliers, institutions and supporters who will foster and grow the adoption of this breakthrough technology,” Croft says. “Additive is growing, and people are starting to take notice.”

He identifies another key driver as being the transition of cutting-edge research out of the university sector into private industry, citing companies such as Aurora Labs, AmPro, SPEE3D and Titomic as examples of emerging businesses that are doing world-leading work in additive manufacturing.

“This will be a multibillion-dollar industry in Australia without doubt,” Croft says.

According to Hunter, the advances in 3D printing are also being noted by traditional manufacturers, who are acquiring additive manufacturing devices to sit alongside traditional processes.

“This is just another tool for the workshop floor,” Hunter says. “It is not going to disrupt their traditional manufacturing processes. But to compete in the market, take on small short-run work and do things that are going to future proof them, they are going to need to adopt this technology.”

–

Content produced in association with Konica Minolta.

ARE YOU READY TO RETHINK TOMORROW? Take advantage of what will be the most exciting period in business, ever. How can technology transform your business?