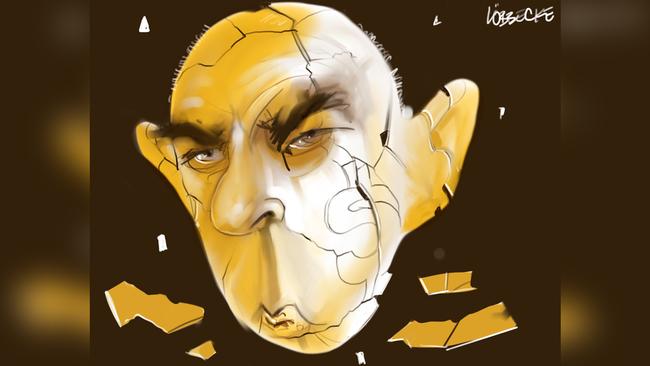

Shareholders will today vent their anger at the Westpac board with a protest vote of about 40 per cent expected against incumbent director Peter Marriott, but the real challenge is to decide who will lead the recovery.

Shareholders may pat themselves on the back by expressing their concerns with a likely second strike on the bank’s remuneration report.

Back in the early 1990s when the late Kerry Packer tried to get control, he acquired a big stake in the bank and attempted to get his offsider Al Dunlap nominated. He failed but at least had a plan.

The board is of course responsible for charting a course to recover from the governance snafu it has presided over, but what role are the shareholders playing in this process?

The same could be said of the board which will go overboard with contrition today, but where is the recovery plan to present to shareholders and where is the name of the next chair to put to the meeting?

Accountability has come through the resignation of chief executive Brian Hartzer and the early departure of chair Lindsay Maxstead. Those boxes are ticked but the recovery plan is the key.

APRA committee member Graeme Samuel is clear, saying there was a governance failure, just as there is one evident in the aged care sector as shown by that royal commission.

He said directors used complexity as a false defence, and argued the governance failures may run across corporate Australia — it’s just only a few sectors have been subjected to an intensive royal commission.

The famed APRA report on CBA outlined a clear line of responsibility starting with the board challenging the executives.

The safeguards come at this level supported by the external and internal auditors and naturally enough the chairs of the board risk, audit and remuneration committees.

Then there are the executives, their remuneration and lines of communication, both with their direct reports and to the board.

Quite clearly these last channels were either not working at Westpac or the information was not acted on, which was the fault of the executives, the internal and external auditors, the board committees and their chairs and ultimately the board.

That is three lines of defence installed to overcome any complexity that have failed.

Throwing everyone off the board makes no sense, which is why it is good that Marriott looks likely to return because the former ANZ finance chief knows banking better than most and is a numbers zealot. The real issue for Westpac is what comes next. There is a view that, as businesses, banks are simply too complex and the expectations of shareholders are too high.

Back in the early 1990s when Westpac nearly went under, John Uhrig stepped up to replace Sir Eric Neal and four other comrades who quit.

In 1992 after staring down Packer, Uhrig famously conducted a two-day marathon annual meeting as the recovery began.

Sadly, for a long time Westpac insiders have rested on the belief that snafus would never happen at the bank because everyone remembers when the bank nearly failed.

The belief turned into arrogance and has now allegedly breached Austrac rules 23 million times, among other issues like liar loans and stealing money from superannuation clients.

That’s the point at which the new guard comes in.

As written repeatedly in this column, the best internal candidate for chair is former KPMG boss Peter Nash, with his only downside being part of the KPMG mafia which has monitored the bank along with PwC for the last 51 years.

There is a strong view in the market that says an outsider is best as both chair and chief executive, but at first instance there needs to be a chair to chart the recovery plan.

At an AICD roundtable this week, Newcrest chair Peter Hay confided: “I wouldn’t join the bank board. You’re expected to be more involved in the management of the bank than traditionally directors have been involved in the business. And I think that’s different.”

That is a big call coming from Hay given he was an ANZ board member for five years until 2014.

There are questions whether the issue of complexity is, as argued by Samuel, a smokescreen for basic governance failure.

Hay is also a former corporate partner at what is now Herbert Smith Freehills. He thinks “there is one rule for banks and one rule for others … the expectations are very high, in the wake of Hayne, in particular.”

Jane Tongs from Cromwell Global questioned whether the governance model at the banks was workable.

The regulation was complex, she said. “I think that’s why boards do struggle to get their heads around it.”

The directors think there should be enough people around a board table who understand the sector.

Hay noted that “if you’re a banker you might join a bank board because you understand it at a more intimate level than non-bankers do”. OZ Minerals chair Rebecca McGrath stressed the need for experience.

In addition, she said, “there’s less acceptance of things being deferred or perhaps the board is taking a more active role in prioritising how things should come back or how actions should be taken”.

This means directors are taking more note and demanding better information.

As to proxy advisers, Hay noted, “I can’t get myself over the cost-benefit of creating further regulation.”

McGrath added: “I think we give them too much oxygen.

“It’s not helping the director profession the way they’re seen to be focused on the evil proxy adviser and regulating them. Because I think that if anything, that gives more oxygen and more influence.”

She noted it was up to their clients whether they were getting quality advice and, like others, argued it was up to directors to talk with shareholders.

Spotlight on super laggards

APRA’s decision to name poorly performed funds is not the first time the funds in question knew they were in the spotlight.

They were highlighted by the Productivity Commission’s report into the industry and of course APRA has already confronted the affected funds to ask what they are doing about persistent underperformance.

The PC recommended APRA be given the power to remove the licences of the recalcitrant funds but the government has yet to act on this request.

Publication is one step but given superannuation is compulsory, a high proportion of members simply accept default positions, and as the funds have a duty to act in the best interests of members more needs to be done.

This is why actual licence removal is one extra form of attack.

The PC argued APRA should run the data over seven years to show full cycle impacts, but the regulator just went back five years.

It is rightly keen to act on its mandate.