No.1: Gina Rinehart, Hancock Prospecting

The spectacular success of Gina Rinehart’s Roy Hill mine has been almost 30 years in the making, with some nailbiting moments along the way | THE LIST: Australia’s Richest 250

What an extraordinary year it has been for Gina Rinehart. The mining magnate tops The List this year with an estimated fortune of $36.28 billion from her Hancock Prospecting iron ore powerhouse. Hancock recorded one of the biggest profits for a private company in recent Australian corporate history when it revealed in November a $4 billion net profit for the 2020 financial year – 50 per cent more than it made in the previous 12 months. Rinehart’s business paid a huge $1.55 billion in company tax, and revenue surged from $8.4 billion to $10.6 billion.

Based on strong iron ore prices and the performance of publicly listed companies such as Andrew Forrest’s Fortescue Metals Group, Hancock may be having an even better 2021.

But dig a bit deeper and what stands out for Rinehart is how 2020 arrived for her and Hancock about four years ahead of schedule – and how the success of her giant Roy Hill mine has been almost 30 years in the making.

THE LIST: Australia’s Richest 250

Roy Hill is undoubtedly the jewel in the Hancock Prospecting crown. It is a little over five years since Hancock sent its first shipment of iron ore off to China from Port Hedland in December 2015. The mine is now processing 60 million tonnes of iron ore per annum and contributes the bulk of Hancock’s profits.

“We are very happy with what we have achieved at Roy Hill – it’s a mega project that contributes significantly to the West Australian and Australian economy and provides many opportunities,” Rinehart tells The List. “I hope that all who have worked on ‘Roy’ can be very proud of their contribution.”

So successful has the mine been that 2020 marked another big achievement: the paying off well ahead of time of almost $10 billion in debt funding that Rinehart clinched only six years ago in a unique and complex deal involving no less than 19 of the world’s largest banks and five export credit agencies.

“We didn’t go to the government for taxpayers’ money, like too many businesses are doing,” she says. “It was great to be able to pay back the banks and ECAs four years ahead of schedule.”

On the surface it looks like a sudden success story, with Hancock doubling in value in a year, but as Rinehart explains, major iron ore mines are not built nor make a profit overnight. “[It took] at least 10 years of government tape and approvals, permits and licences – more than 4000 pre-construction, with more for construction – added to the cost, time and risk. We took longer as our company [Hancock], the majority owner of Roy, was left in a hazardous financial position back in the early 1990s – not able to pay off debt until 2000 – so we couldn’t explore, study or develop as fast as we would have liked, given the shortage of money back then.”

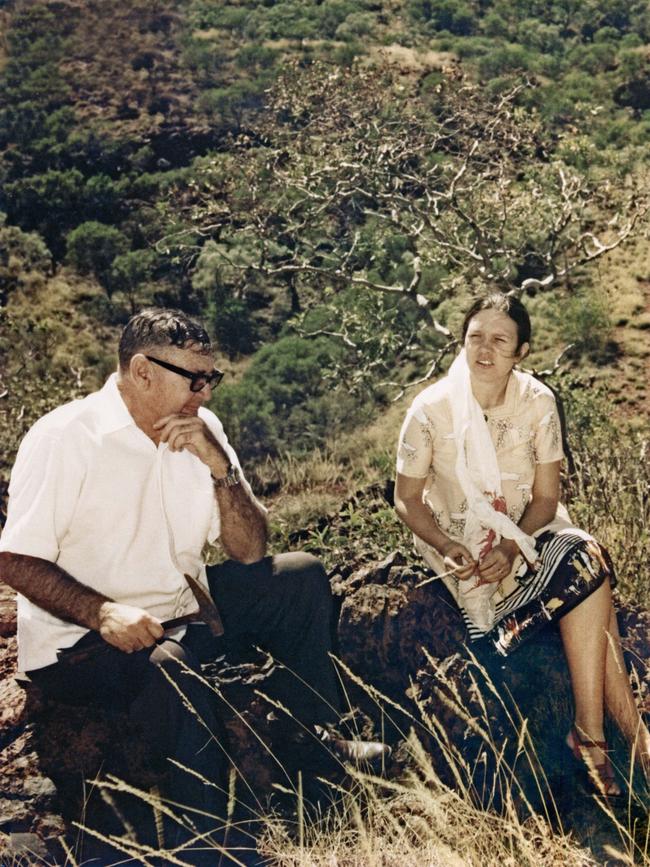

Rinehart had acquired the tenements to Roy Hill in 1993, a year after her late father Lang Hancock died, and remembers being repeatedly advised not to press ahead with the mine because her company was too small, lacked the necessary resources to pull off such a big project on an asset BHP had discarded, and so on.

It would take the best part of two decades for work on gaining all the necessary approvals, even before the huge $US7.2 billion debt financing package was put together in 2014.

Rinehart remembers one of the major contractors on the mine’s preparation plant going under and delaying financing, and she even drew up closure plans. Before then there was a race against time to prepare documents for a Bankable Feasibility Study that was submitted with moments to spare.

“I [also] think of being told a few years ago, after landing at Ginbata, Roy’s airstrip, that it would be ‘impossible’ to meet a milestone required by our debt providers. When I told our staff there at a meeting I called that we had no Plan B, we must meet the milestone, and to re-study what we could do from start to finish, our staff rose and did the ‘impossible’. We made that bank requirement, with hours to spare.”

The milestones that have since been achieved at Roy Hill make extensive reading.

It is the fastest integrated iron ore operation to be constructed in Western Australia’s Pilbara and operates some of the world’s largest mining equipment, including a huge bucket wheel reclaimer and the fastest rail car dumper unloader. It is estimated that the mine will pay far more than $11 billion in taxes and royalties over its lifespan. Roy Hill also uses drones onsite, and has seven fleets of pink mining trucks, two pink locomotives, and 130 pink ore cars to raise support for breast cancer.

The mine has also managed to operate without disruption during a global pandemic.

“We were very quick to act with introducing testing and mask-wearing, among other things, and we’re advised that the Chamber of Minerals and Energy of West Australia [CME] adopted our protocols and shared these with their other members,” says Rinehart. “I’m very pleased to be able to say not a single one of our staff contracted COVID.”

Hancock has also made a string of acquisitions in recent years, including the $427 million takeover of Atlas Iron and the huge S.Kidman & Co pastoral business for which Hancock and Shanghai CRED paid $386 million. There are other assets in its portfolio, such as a potential iron ore mine at Mulga Downs near Roy Hill. That means there is still plenty of work for Rinehart and Hancock to get done, despite Roy Hill’s big success.

“At Roy Hill we plan to further invest in the business and expand our capacity up to 70 million tonnes [per annum]. We are also working to achieve synergies between Roy Hill and our other projects, with Atlas Iron and Mulga Downs,” Rinehart says.

“We have a number of projects in the pipeline, [it is] a very busy year this year.”