Lessons of Enron debacle must never be forgotten

It’s 20 years since the greatest corporate scandal of modern times – investors need to know what happened to ‘the smartest guys in the room’ and why it must not happen again.

Thursday, December 2, marks the 20th anniversary of Enron’s bankruptcy, a date that shall live long in financial infamy.

At the time it was the largest bankruptcy in US history and the first in a series of financial catastrophes that threatened to destabilise the economy.

Investments evaporated, jobs were lost, reputations were destroyed, a famous accounting firm collapsed and people went to jail.

The perceived failures of Enron’s board and executives served as a primary impetus for the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the corporate responsibility movement.

As such, Enron remains one of the most consequential corporate governance and finance developments in history.

It’s a development with which the new generation of corporate leaders – the ones who have entered the boardroom since then – may not be fully familiar. But to them, their colleagues, their advisers and their investors, Enron still matters.

The Enron saga began with its creation as an electricity and natural gas pipeline company that, through mergers and diversification, transformed into an energy-based trading and data management enterprise engaged in various forms of highly complex transactions.

Among these were a series of unusual and complicated limited-liability, related-party transactions in which some members of Enron’s management team held lucrative interests, and which allowed the company to transfer certain liabilities off its financial statements.

As the company’s stock price reached its peak in August 2000, some Enron executives began to sell their stock, allegedly on the basis of inside information regarding undisclosed losses.

At the same time many investment advisers continued to recommend Enron stock to their clients. By March 2001, a series of media reports began to question the sustainability of Enron’s stock price, including a prominent article in Fortune that identified potential financial reporting problems.

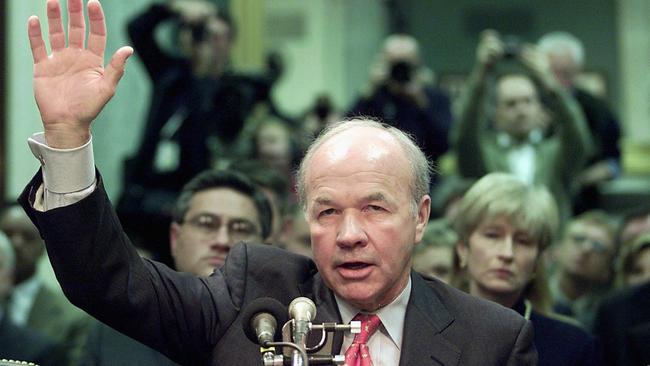

Over the next several months, its stock price collapsed, years of its financial statements were restated, CEO Kenneth Lay resigned, a bailout merger failed, its credit was downgraded, and the Securities and Exchange Commission began an investigation of its dealings with related parties.

On December 2 it declared bankruptcy. Multiple regulatory investigations followed, several criminal convictions were obtained, and Sarbanes-Oxley legislation in the US was ultimately enacted to curb the perceived abuses arising from Enron and several similar accounting scandals.

The shocking costs of Enron’s collapse were spread broadly among a number of interests: the shareholders, most of whom lost the bulk of their investments; the employees, many based in Houston, who lost their jobs; the investment analysts misled by the Enron financials; the executives who received prison sentences; and Enron’s auditor, the venerable Arthur Andersen, which collapsed following an obstruction-of-justice conviction (ultimately reversed by the US Supreme Court).

The abuses that prompted the catastrophe were multifold. They included an intricate business model that made external monitoring difficult. Complex financial statements confused stockholders and analysts alike.

There were also highly aggressive revenue recognition and “mark-to-market accounting” practices, speculative special-purpose entities and the management conflicts they presented, a governance structure that lacked the expertise to monitor the business and its financial practices, and an overly aggressive corporate culture that placed little value on ethics and compliance.

These abuses were “front and centre” to the drafters of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Legislative responses to the various transgressions can be found throughout the Act, including its treatment of oversight of the accounting profession, auditor independence, the credibility of the board’s audit committee, the integrity of financial statements, the ethics of financial officers, whistleblower protections, and preservation of documents.

The Enron abuses also prompted substantial enhancements to governance principles and to the professional ethics of attorneys.

But their impact and influence notwithstanding, no combination of legislation, law enforcement, professional regulation and best practices can provide assurances to any company or board of directors that the “smartest people in the room” won’t resurface in any business, at any time. It’s human nature.

Some people will be “pushing the edge of the (business) envelope” all the time, most in the best interests of the company, but some not so much.

These past abuses are worthwhile lessons for today’s corporate leaders, many of whom weren’t in similar positions 20 years ago. These leaders likely lack the near-visceral reaction to the word Enron that more senior, and perhaps now retired, leaders retain. There’s a reason Enron is a metaphor for mega-scandal.

The more familiar that corporate leaders are with the Enron saga, the more likely they are to support the integrity of financial statements and effective corporate governance.

Leaders who understand how financials can and have been manipulated are more likely to insist on their accuracy. Leaders who understand the rationale for a company’s governance policies are more likely to follow than dismiss them.

Leaders who are familiar with the failures of the Enron board are more likely to recognise indicators of similar conduct on their own board.

For them, their companies, and their stakeholders, Enron still matters.

Barron’s

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout