The former federal government minister and close adviser to Kerry Stokes has been going to China for more than 30 years, from his days as a young politician after winning the Tasmanian seat of Bass in 1984. Since then he has worked for Macquarie Group in its business with China and for many years on the business interests of Stokes in China.

Smith, who is also the head of the Business Council’s committee on China, chaired the Australia-China Relations Council for the past decade and was asked last year to chair the foundation being set up to succeed the council, a wealthier organisation to be called the National Foundation for Australia-China Relations.

Announced with great fanfare last year, it was due to kick off this year after a year of planning.

But somehow the grand plans for the foundation, which was to play a role in rebooting the strained Australia-China relationship, have never materialised.

Even before the COVID crisis, there were concerns the foundation did not seem to be getting off the ground, and questions about exactly who would lead it and what it would do.

Expectations were that the organisation, which already has an office in Sydney’s George Street, would be run by an official from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

But no announcement has come and plans for a grand launch were put on ice.

In February, Smith quietly decided it was time to step aside from the foundation and concentrate on his business interests.

While he has kept a low profile, he confirmed he felt the organisation should be seen to be independent of government if it was to do its job of trying to reboot relations with China.

One rumour has it that the government might ask Australia Post CEO Christine Holgate to take over from Smith.

Holgate has been going to China for many years, particularly in her former role as CEO of Blackmores.

While it only emerged this week, it seems Smith’s departure may signal differences of opinion, including with the business community on the Morrison government’s ties with China, which were evident well before this week’s diplomatic stoush over Foreign Minister Marise Payne’s call for an independent inquiry into the origins of COVID-19.

Smith is a busy man and Australia-China relationships are made of many contacts by people over many decades, such as Fortecue Metals chairman Andrew Forrest, who remains passionately committed to long-term ties with China.

But even before the febrile events of this week — and the COVID crisis — questions were being asked whether the lack of action on the foundation signified a problem in terms of the government’s view of relations with China.

Now, just when it seemed like we were coming out of the COVID-19 crisis much better than many other countries, Australia has found itself involved in another furore with China, its largest trading partner.

The Australia-China business community, which has a strong relationship with China stretching over decades, is privately furious that the week has seen a major diplomatic dispute between the government and the Chinese embassy in Canberra that seems to have got out of hand.

After weeks of taking a low profile when the Department of Foreign Affairs was working around the clock to help Australians stranded around the world on cruise ships and trapped by border controls, Payne pops up on TV on Sunday to argue the case for an inquiry into the origins of COVID-19.

While some sort of inquiry may be a good idea, Payne’s comments about the need for much more transparency set off China’s ambassador to Australia, Cheng Jingye, who replied in an interview with the Australian Financial Review.

A careful reading of the transcript, on the website of the Chinese embassy, shows him arguing that this appeared to Beijing as Australia teaming up with the US to “launch a political campaign against China”.

Cheng, like other Chinese, is sensitive about declarations that the origins of the virus were in the city of Wuhan.

Pressed about what Payne’s call for an inquiry into the COVID-19 crisis might mean, the ambassador did agree that it could have implications for Australian trade with China, but a careful reading of his words did not amount to a threat of retaliation.

However, the situation went from bad to worse on Wednesday with the embassy’s extraordinary decision to release its version of a conversation between the ambassador and the secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Frances Adamson, herself a former ambassador to China.

China does not handle soft diplomacy well and the embassy’s moves have thrown fuel on the fire. It would have been far better off to have let the matter lie.

But the damage has been done and there is now real concern about the implications for trade with China, which helped Australia stave off a recession in the wake of the global financial crisis.

The business community is not naive about relations with China and the need for government to raise issues with Beijing. But there are real questions being asked about whether the furore sparked by Payne’s call for an inquiry and her comments to David Speers on the ABC’s Insiders on Sunday could have been handled differently — in a way that did not wave fingers directly at China.

Australia’s record trade with China — in iron ore, coal, LNG, wine, food, tourism and education — comes from a complementarity in what Australia supplies and China needs.

As the chief of the Australia China Business Council, Helen Sawczak, pointed out, trade with China is at record levels because Australian companies want to do business with China.

The latest trade figures show that Australia’s trade with China is increasing. As James Laurenceson, director of the Australia China Relations Institute at Sydney’s UTS, points out, China’s share of Australian goods exports was 38.1 per cent at the end of last year and had risen to 38.4 per cent in the latest figures showing trade until February.

Diversification of trade away from a strong reliance on China is a good idea, but good luck with that.

Government after government has launched trade missions to India, Japan, Indonesia and a host of other countries but no bilateral relationship has driven trade relations like the one between Australia and China.

There is no other country demanding our iron ore or beef or wine or LNG or education services and other products to anywhere near the same degree as China.

Indonesia, which is often touted as a major potential buyer of more Australian products, is in a serious situation with its own COVID-19 crisis.

Trade with India, often touted as another buyer for our goods, continues to disappoint.

As some observers noted, there are good reasons why diplomacy is usually conducted behind closed doors.

For its part, Beijing continues to react strongly to comments made by Australian politicians — even when carefully worded — yet manages to cop the torrent of abuse from the Trump administration without suggestions of breaking off US trade relations.

The Australia-China business community is watching the diplomatic furore with considerable concern.

“Business is concerned about any deterioration in the political relationship (with China),” Sawczak says. But it still “remained overwhelmingly confident about trade with China.

“China will be the key to our economic recovery post COVID-19, just as it was after the global financial crisis in 2009.”

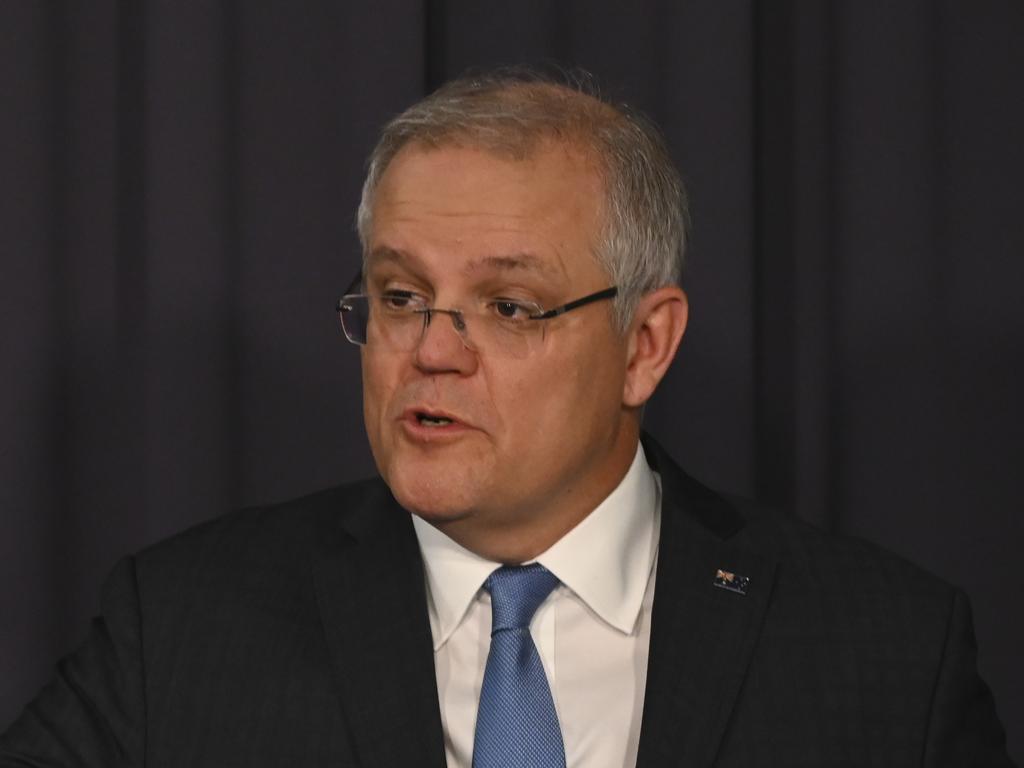

Sydney businessman Warwick Smith is one of Australia’s most experienced China hands.