The sisters whose DNA kit test results blew apart their family as they knew it

The sisters bought two DNA kits. In an age of direct-to-consumer genetic testing, they found some secrets are impossible to keep.

Sonny and Brina Hurwitz raised a family in Boston. They both died with secrets.

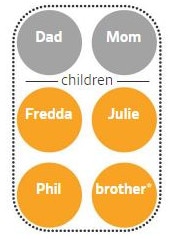

In 2016, their oldest daughter, Julie Lawson, took a home DNA test. Later, she persuaded her sister, Fredda Hurwitz, to take one too.

In May, the sisters sat at the dinner table in Ms Hurwitz’s Falls Church, Virginia, home to share their results. A man’s name popped up as a close genetic match for Ms Hurwitz.

Neither had ever heard of him.

Ms Lawson searched for the man on Facebook. When she saw his photos, she knew.

He looked like their late father. Based on his age and the close physical resemblance, Ms Lawson told her sister: “He’s got to be our brother.”

This was their father’s secret. He had a child they never knew about.

Then came a second shock.

Ms Lawson’s test showed no visible genetic connection to this new man.

This was their mother’s secret: Ms Lawson was the product of a brief extramarital affair.

The man who raised her wasn’t her biological father.

“My life was a lie”

The revelations ricocheted through the family. They created new bonds with people who were once strangers.

They caused tension with family they had known all their lives. And they sparked a fight between the sisters about the bonds of loyalty — and how much their parents should have told them.

Ms Lawson, 65, is still grappling with “the pain of knowing my life was a lie and having all these questions that can’t be fully answered because both my parents are gone.”

The hardest part came the moment she and Ms Hurwitz, 52, realised they were half, not full, sisters.

“We held each other,” Ms Lawson said, “and we sobbed.”

At a time of ubiquitous direct-to-consumer genetic testing, family confidences are almost impossible to keep. Companies sell their products for under $140.

Millions of DNA kits have been sold in recent years, handing g over information both useful and shocking.

Sales of the tests are soaring as people seek to learn more about their roots.

Ancestry, whose tests the sisters used, reported sales of $US14 million ($AU19.4 million) DNA kits worldwide as of November, 2018 — up from 3 million in 2016.

A paper published in Genome Biology, a scientific journal, last year estimated more than 100 million people will have their DNA tested by 2021.

Ancestry provides customers who choose to do so with a way to connect online with others who are DNA matches.

“Secrets will come out”

The company said it has “a small, dedicated group of highly experienced representatives who speak to customers with more sensitive queries.”

Genetic counsellor Brianne Kirkpatrick, founder of Watershed DNA, which provides consultations to people with DNA questions, advises clients to consider how and whether to share certain information. “If you have a secret or think something might be uncovered through DNA testing, start preparing what you want to share ahead of time when you can be in control,” she said.

Ms Kirkpatrick sometimes suggests clients write letters, explaining details behind their children’s genetic origins, which they can give if the secret is revealed.

“I have become of the mindset it is not a matter of if the secrets will come out,” she said. “It is a matter of when the secrets will come out.”

Given the rapid growth of consumer genetic testing, people can often be identified even if they don’t take a test themselves. Some people who take tests share family trees online. Amateur genealogists and researchers can identify additional connections through obituaries, wedding announcements, and other public information.

In a paper published in October in the journal Science, researchers estimated over 60 per cent of individuals of European descent in the U.S. now have a third cousin or closer relative in a database.

“DNA tests can reveal that there is something odd going on,” said Yaniv Erlich, one of the authors and chief science officer of DNA-testing company MyHeritage. “But they don’t tell you the story of what happened.”

Stranger who looked like Dad

In Falls Church, their test results back, the sisters stared at pictures of a stranger who looked like their Dad.

Ms Hurwitz, exhausted and emotional, told her sister she was going to sleep.

Ms Lawson didn’t want to wait.

She messaged the man, Dana Dolvin, telling him an Ancestry test showed he was a relative, suggesting they talk.

He responded right away. He lived near Falls Church and agreed to meet at Ms Hurwitz’s home the next day. He assumed they might be cousins.

The sisters showed him picture after picture of their late father.

The resemblance was uncanny: the eyes, the ears, the height, even down to the glasses and love of wearing hats.

Mr Dolvin, 62, never met the man listed on his birth certificate as his father, who was his late mother’s husband.

The couple, both African-American, divorced after his birth. In pictures, Mr Dolvin didn’t look like him.”

Mr Dolvin’s own DNA test results indicated he was 47 per cent European Jewish.

“I kind of figured my Dad was a fair-skinned person,” he said.

He wasn’t sure he would ever identify his father, or even if the man was still alive.

Relatives might not want to share information, or might not approve of the fact his parents weren’t the same race.

“People don’t want to rock the boat,” he said. “They also may have different feelings toward people of colour.”

The sisters knew their parents had marital difficulties over the years, so it wasn’t a shock to learn their father had an affair.

Their parents’ circle of friends included people of different religious and racial backgrounds. They were unsurprised their father had an interracial relationship.

“My surprise was that a child existed,” said Ms Hurwitz. “And he looked so much like Dad.”

Mr Dolvin wondered if the women really were his siblings.

It was hard to believe, he said, “that I finally got an answer to the question haunting me for such a long time.”

Siblings share around half their DNA. Half-siblings share a quarter, and first cousins, on average, share 12.5 per cent.

Mr Dolvin’s shared DNA with Ms Hurwitz indicated they were half-siblings.

A boy named Hy

Ms Lawson couldn’t sleep. Why hadn’t Mr Dolvin’s name come up on her results? Why did he have a genetic relationship only with her sister?

She asked help from Larry Alssid, 64, a Long Island, psychologist, who had contacted her after his own Ancestry test showed they were related. They could never figure out the connection, but kept in touch.

Dr Alssid suspected Ms Lawson might have a different biological parent than her sister, but didn’t want to be the one to tell her the potentially shattering information.

“I slept on it,” he said.

He told her to check the amount of DNA she and her sister shared in common. Soon she understood: She and her sister didn’t have the same biological parents — or father, to be precise.

“I did regret I told her because she was in shock,” Dr Alssid said. “We still didn’t know who her father was.”

Later, Dr Alssid consulted a family tree and gave her names of four brothers — distant relatives he’d never met — who could be a match, with two youngest, Jack and Ira Greenberg, the most likely.

“Jack or Ira? My mother never mentioned those names,” Ms Lawson recalled saying.

She doubted she would find the answers she wanted.

Dr Alssid told her a nephew of Jack and Ira might know more.

His reply email said the brothers went by nicknames. The youngest, Ira, was known as Hy.

“That is when I knew,” said Ms Lawson. “My mother always told me that her first love was a boy named Hy.”

Hy Greenberg was the only brother still alive. An 89-year-old retired travelling salesman, he never married and was living in Florida.

He agreed to a phone conversation.

She started slowly, telling him she was doing a family tree. Did he know a woman named Brina?

“Yes. I dated her, my best friend introduced us,” he said.

Later in the conversation, she asked the key question. “I have to get personal,” she said. “Would your relationship have included sex?”

Mr Greenberg said yes.

“You are my father,” Ms Lawson told him. “I am your daughter.”

“You’ve got to be kidding,” Mr Greenberg said.

Mr Greenberg had never done a DNA test, and struggled to understand how Ms Lawson could use the results of other relatives of his to identify him as her father.

Later, his own kit results would reveal they were parent and child.

During their first call, he shared details of his early dates with her mother after he got out of the Navy. She wanted to get serious, he said, but he told her he wasn’t interested in marrying. They briefly rekindled the connection years later, after her mother was married. Then they parted ways again.

“Welcome home”

He never imagined himself being a father, but their similar sense of humour and love of storytelling saw the conversation last hours.

She suggested they meet. He hesitated, then said, “You want to come, come.”

In June, Ms Lawson knocked on the door of her biological father.

It was Father’s Day weekend. He called her darling and gave her a hug.

“Welcome home,” he said.

The visit led Ms Lawson and her sister to have an intense fight.

Ms Lawson posted a picture of herself and Mr Greenberg on Facebook, saying she was spending her first Father’s Day with her father.

“I was furious,” said her Ms Hurwitz. “I was in tears. I told her Dad is still Dad, and you have just negated his entire existence and everything he ever did for you with that one post.”

Ms. Lawson said she never meant any disrespect to their late father. “I felt misunderstood,” she said. “My brain was so caught up in what is going on.”

She says she feels a powerful emotional connection to her biological father. The next time she went to see him, she took her sister along.

Meeting him was difficult for Ms Hurwitz. She wondered if he was the man her mother preferred over her father: “I didn’t know what to say or how to act.”

“It’s a lot to take in”

Getting to know her new half brother, Mr Dolvin, has been easier.

And has answered questions for him.

“I finally got the answer that wasn’t supplied to me by people who loved me and who I loved,” he said.

Growing up, his cousins teased him about the light colour of his skin, calling him “white boy,” he said. An only child, he frequently asked his mother about his origins.

“Don’t worry about it,” he says she told him. He stopped asking when he was a teenager; his mother died decades ago.

“I was still curious, but no one would tell me,” he said. “Emotionally, you wish it could have been another way, but unfortunately, it isn’t.”

In the months since they met, the sisters, Mr Dolvin and their families have met for dinners and outings.

In Boston, Ms Lawson took Mr Dolvin around the neighbourhood where she grew up, pointing out family landmarks. He refers to both women as his sisters, even though he shares a biological father with only one.

So far, the sisters’ other two siblings, both men, haven’t expressed interest in meeting Mr Dolvin. Phil Hurwitz, 63, was born six months before Mr Dolvin and is unsure “how I want to move forward.”

Ms Lawson got upset with Phil and asked him when he might feel ready.

“I told her I am not putting a time frame on it,” he said. Their other brother didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Mr Dolvin says it’s not his place to contact the two brothers: he’ll let them decide “if they want to welcome me or say ‘hi’…” His voice trailed off for a moment.

“Maybe they don’t feel comfortable with it yet. It’s a lot to take in.”

“Another world, another time”

Ms Hurwitz says news that both parents had children from extramarital affairs forced a reckoning she’s not sure her brothers were ready to make.

“They have to reconsider completely who their parents were, the lessons they taught us, what they stood for,” she said. “Everyone deals with the emotions differently.”

She looked at her sister, who cried quietly at the table. “It is not up to me to judge the decisions Mom and Dad made,” Ms Hurwitz said.

“It was another world and another time.”

Ms Lawson said: “I have a hard time when people say it’s the past, move on.”

Mr Dolvin put his arm around her, comforting her. “I like that we are all together. I’m here. I’m sitting with you.”

There are many unresolved and hard-to-answer questions, like if their father was ever told Mr Dolvin was his son. They don’t think so. “I believe if he knew about Dana, he would have tried to reach out,” Ms Hurwitz said.

Her father owned a popular kosher deli in a Boston neighbourhood. Mr Dolvin’s mother worked as a cosmetologist in a nearby predominantly African-American neighbourhood.

Both loved jazz; the siblings speculate they might have met at a jazz club.

The sisters believe their mother knew Ms Lawson was the product of her own affair.

Ms Lawson and her mother had a difficult relationship, and both sisters think the revelation explains why: “Julie was a reminder of what Mom did”.

“She had to deal with the consequences every day,” Ms Hurwitz says. “How did she keep the secret from Dad?”

Secrets and graves

Both sisters know they can’t be sure what either parent shared with the other.

When Ms Lawson was 29 and Ms Hurwitz was 16, their parents divorced — and then got remarried nine years later. They stayed together until he died in 2006. She died in 2016.

Ms. Lawson says she told her mother she got DNA test results back, but her mother wasn’t interested in talking about them.

She died before the second sister took the test whose results revealed so much.

The sisters always return to how much their parents should have told them. Even now, hurt and tensions sometimes flare.

“I understand why you wouldn’t tell,” said Ms Hurwitz. “The implications of revealing the secret have a domino effect.”

Her sister vehemently disagrees. “Every man has a right to know he has offspring,” said Ms Lawson. “Every child has the right to know her origins. We missed 65 years together.”

Ms Lawson wears a birthday present she received from Mr Greenberg, a necklace of two open hearts connected by her birthstone. She is helping plan a party for his 90th birthday in March.

The sisters learned the truth and now are learning to live with the uncertainties.

“I have my anger, my compassion, and my understanding, and I can separate all those emotions,” Ms Lawson said.

Ms Hurwitz leaned in closer to her sister.

“Every family has secrets,” she said.

— The Wall Street Journal