Thai cave rescue: What lies beneath? Vague mapping complicates operation

In the mission to save the Thai boys, rescuers could only feel their way, laying guide ropes and making sketches as they went.

The mission to rescue 12 young soccer players and their coach from a cave in Thailand is fraught with danger.

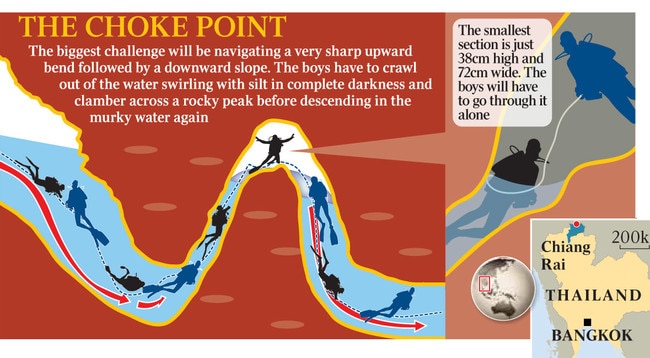

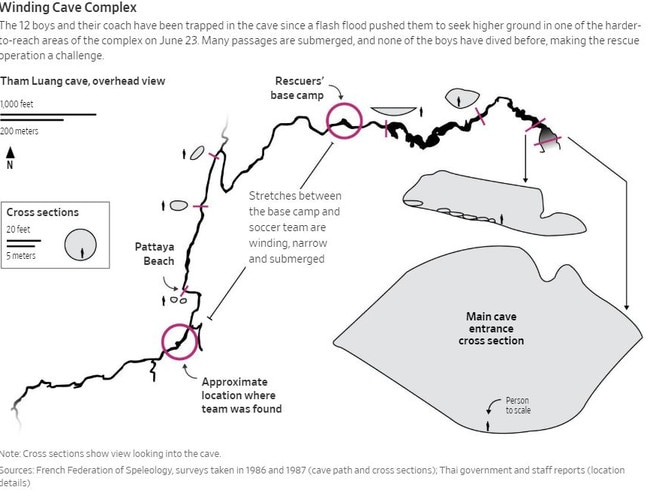

The success of the elite rescue divers hinges on traversing miles of caves and narrow passageways submerged by a flash flood that cut off the boys when they were exploring inside just over two weeks ago. The most hazardous obstacle is a submerged choke point 15 inches (38cms) across, shaped like the U-bend in a toilet. One former Thai Navy diver died last week after expending his air trying to make it through.

With oxygen levels inside Tham Luang cave deteriorating and more monsoon rains on the way, rescue leaders gave the go signal to kit out the boys with scuba gear and guide them out through the murky water one by one. Some eight hours later, the first four were rescued, Thai Navy SEALs said. None of the boys had dived before, and officials expect it will take two or three days to get them all out.

“Visibility is bad. It’s very difficult to keep your bearings, and the maps are limited,” said Ben Reymenants, a Belgian diver who assisted the rescue effort. “It is incredibly dangerous.” Rescue co-ordinators say they have no other choice: Despite a week of efforts, engineers, geologists and oil-industry specialists have been unable to pinpoint the location of the boys to construct an escape shaft.

Just as the search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 revealed that the surface of the moon was better mapped than the Indian Ocean sea floor, the cave-rescue attempt shows that much beneath our feet is a mystery. Around the world, ramblers and cave explorers often stumble across new caverns, and sinkholes open up without warning on suburban streets.

The caves we know about are often sparsely mapped. The appeal of discovering new, hidden worlds is a big part of why spelunkers are drawn to cave exploring.

But it is also why cave rescues are so dangerous, experts say: Rescuers often have only a sketchy outline of what lies ahead, especially away from the main haunts of amateur cave explorers in Britain, Europe and North America.

Modern technology is of little use — the rock blocks signals from satellites to GPS devices, although radio beacons can sometimes be helpful. Amateur cave cartographers instead rely on tools as basic as a compass and measuring tape.

“The results can be, well, variable,” said Bill Whitehouse, vice chairman of the British Cave Rescue Council.

Tham Luang cave didn’t get its first map until 1986. The work of French hobbyists, it was little more than a carefully drawn sketch, and though British spelunkers have annotated as best they could in the years since, there is still no accurate indication of how high or low the cave goes. In 2014, an attempt to use GPS to verify the precise location of the entrance revealed the map was off by dozens of yards.

So when the soccer team went missing, rescuers could only feel their way through, laying guide ropes and making sketches as they went. It was nearly 10 days before two British divers made contact with the boys and their coach.

Getting them out is an even bigger challenge.

“If we knew their exact location, then we could just drill straight into the cave and pull them out, but we don’t know their exact position,” said Thanes Weerasiri, an expert with the Engineering Institute of Thailand who is assisting the search.

Authorities figure the boys are anywhere between 600 and 1,000 yards down, and their lateral location is just as uncertain. It makes the team much harder to extract than the 33 miners trapped in Chile’s Copiapó mine after a shaft collapsed in 2010. Rescuers there had to drill down some 700 yards, but at least they had an idea where to start.

In Thailand, local governor Narongsak Osottanakorn said surveyors dug more than 100 pilot holes into the mountainside. So far, none appears to be on target.

Among those pitching in is entrepreneur Elon Musk, who sent engineers from his space-exploration and drilling companies to Thailand. “Boring Co. has advanced ground penetrating radar & is pretty good at digging holes,” he wrote on Twitter this past week.

Even if rescuers managed to pinpoint the boys’ location, drilling presents a new set of obstacles. For one, there is the difficulty of placing large drills on top of a thickly forested hillside. Doing so would likely require new roads to be built.

“In Chile, we were in the middle of a desert so you had plenty of room, whereas you are in a mountainous region. The difficult bit is finding space to set up a drill rig,” said Jeff Roten, a drilling-equipment specialist at Schramm Inc., which worked on the Chile rescue.

The composition of the mountain’s interior is also unclear. Some experts warned if the cave where the boys are trapped is pressurized, then drilling a hole could simply suck water levels higher. “That could flood the thing immediately,” said Richard Soppe, a senior engineer at drilling firm Center Rock Inc., who advised on the Chile rescue.

Given the risks, rescue organisers in recent days prepared some unorthodox rescue plans, such as recruiting locals who climb rocks to harvest birds’ nests to make a sought-after glutinous soup. They reasoned that these nest gatherers know how to find their way into tight spaces and might also identify the bird song that some of the children have reportedly said they could hear from inside the cave.

It was a measure of how much the rescuers didn’t want to fall back on their least favoured option: Taking the children out through the cave itself.

With Jake Maxwell Watts

The Wall Street Journal