Smartphone future put on hold as it loses its power to amaze

The last rites are being given to the device that changed our lives, as era of smartphone supremacy begins to wane.

Steve Jobs took to a stage a dozen years ago this month to introduce a revolutionary new product to the world: the first Apple iPhone.

That groundbreaking device, and the competitors that followed, changed the way people communicated, ordered dinner and ordered a taxi. The technology world reoriented around the smartphone, supplanting the personal computer, MP3 players, the digital camera and maps. And the mobile economy was born.

Today it looks as if the era of smartphone supremacy is starting to wane. The devices aren’t going away any time soon but their grip on the consumer is weakening. A global sales slump and a lack of hit new advances have underlined a painful reality for the matured industry: smartphones no longer look so singularly smart.

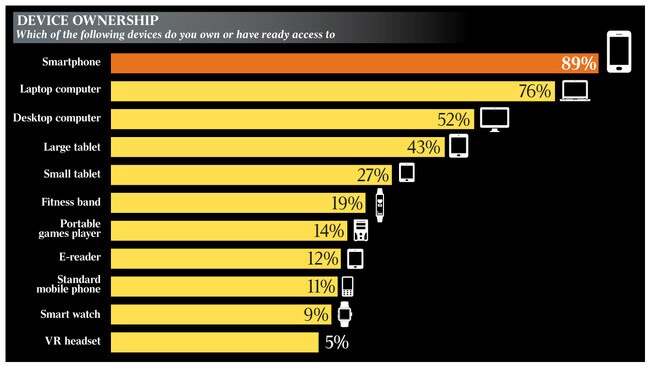

While once smartphones were like a centripetal force sucking up tools from dozens of devices, from torches to calculators to game consoles, functions are now flying out of phones and on to other products with their own embedded smart connections. Watches can now text emojis. Televisions can talk and listen. Voice-activated speakers can order nappies.

The number of “connected” devices in use that can stream music, clock mileage or download apps has more than doubled to 14.2 billion in the past three years, according to market researcher Gartner. The total excludes smartphones.

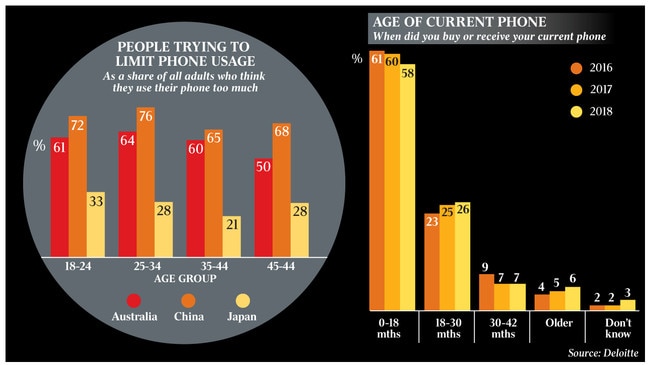

In Australia, an early adopter of technology, the pace of the smartphone invasion has slowed since 2016, according to Deloitte’s 2018 Mobile Consumer Survey.

Almost 90 per cent of those surveyed had smartphones — close to market saturation — and only 11 per cent had an old, less-than-smart phone. Close to 40 per cent of those polled felt they used their smartphones too much.

“We’ve not yet reached ‘peak smartphone’ — the peak level of usage before we expect the vast majority of consumers to begin actively limiting their phone use,” the Deloitte report says.

The “fear of missing out” rush for the latest handset has weakened its grip a little; last year 58 per cent of the users surveyed had phones less than 18 months old, down 3 per cent on 2016. The weaker Australian dollar also has encouraged consumers to put off buying a new phone, especially if they’re Apple users.

“If slightly better cameras, battery life and changing screens are not swaying consumers to upgrade, the next big upgrade for smartphones is set to be 5G, which will fundamentally change how we consume mobile data and will require new hardware to enable connectivity,” the report says.

What has shifted most in the developed world is the smartphone’s monolithic status as the device that software companies and businesses need to reach mobile users — and for consumers to access their services. Now the universe has expanded to voice apps, car infotainment centres and wearable devices.

“We may even need another word for whatever the smartphone will become because when ‘smart’ is everywhere that term becomes almost meaningless,” says Wayne Lam, a principal analyst at research firm IHS Markit.

Like the arc of the personal computer, smartphones — now more a need than a luxurious splurge — are engaged in a race to the bottom. The industry’s two titans, Apple and Samsung, risk seeing their high-end phones become commoditised as Chinese rivals Huawei and Xiaomi prove capable of making similar devices at lower prices.

Twelve years after the iPhone’s debut, more than half of the world’s population owns a smartphone. While that leaves billions of potential first-time buyers in countries from Indonesia to Brazil, they reside in poorer areas, offering lower profits. Meanwhile, the market in some wealthier countries such as the US has become saturated, as the improvements in the devices become more incremental and many consumers have decided they don’t need to get each new upgrade.

As recently as 2015, annual smartphone shipments grew at a double-digit clip. Those days are over: the industry saw its first declines at the end of 2017 and remained negative all last year. A major driver was China, the largest smartphone market, where annual shipments sank 16 per cent, according to government data.

Apple this month made a rare cut to its quarterly revenue forecast, citing slower-than-expected iPhone sales in China.

Samsung followed with a warning of its own, telling investors its fourth-quarter operating profit would decline 29 per cent. The South Korean company feels the smartphone strain doubly, as a handset maker and a components supplier to many rivals, including Apple.

Cao Yuqian, a 24-year-old student in Shanghai, had long made a habit of buying a new phone every year — her iPhone 8 Plus is her 10th Apple device. But this year she’s in no rush to upgrade because leaping to the next generation of iPhones will mean losing the physical home button on the front of the device.

And there’s another reason. “Now it’s a bit pricey,” Cao says.

This month Apple chief Tim Cook has stressed that the company’s product pipeline is strong and he has touted the success it has had beyond the iPhone, selling wearables such as its AirPod wireless headphones and the Apple Watch.

The picture is different in India, where fewer than one in four people owns a smartphone and its user base is growing faster than any other country. But the average price for a smartphone there is about $US160 ($220), or half of what most of the world typically spends, IDC says.

In developed markets, smartphone usage may be reaching its upper limits, as some consumers pull back amid the tech industry’s acknowledgment their products can be addictive, spur anxiety, distract drivers and cast a pall of silence over the dinner table.

Apple and Facebook, for instance, have created systems that track users’ screen time and notify them when they’ve reached preset limits.

Brian McElhaney, 32, an actor, writer and director in New York, became so concerned with his smartphone usage that last year he ditched his iPhone for a $35 flip phone. He reaches for his deactivated smartphone only at night — on his home Wi-Fi — when he needs to access social media apps to post work content and says he can go days without touching it.

“I went whole hog into this technology without really knowing what it was going to do to me,” McElhaney says of smartphones.

More than a third of consumers look at their smartphones within five minutes of waking up and about 20 per cent say they check their phone more than 50 times a day, according to Deloitte’s omnibus survey of 53,000 people in countries around the world.

When Jobs, then Apple’s chief executive, introduced the iPhone from a stage at the Macworld expo in San Francisco in 2007, the crowd burst out clapping the first time he showed them how the phone could be unlocked by swiping a finger across the screen. When he used his finger to scroll through the music on the phone, they cheered.

For years after, phone makers would routinely amaze consumers with new advances, from selfie cameras to waterproof designs to plus-size screens. The early flourishes, though, have more than satiated many consumers who aren’t lured by wireless charging or augmented reality.

As advances became more incremental, Apple and Samsung saw their once-sizeable gaps narrow with lower-cost Chinese rivals such as Huawei, Xiaomi and BBK’s Oppo.

Chinese vendors now make most of the world’s phones — crossing that threshold for the first time last year, according to Canalys, a market researcher. The handset industry is hopeful the coming next-generation 5G networks, which could be 100 times faster, will unlock new uses for the smartphone and entice people to upgrade en masse. Some of those planned changes include better synching with cars, kitchen appliances and home electronics.

“I don’t think we’ve hit peak utility for the smartphone. I think it continues to grow in importance in our lives,” says John Foster, chief executive of Aiqudo, a platform that creates voice-enabled commands for mobile apps.

While the earliest 5G-compatible smartphones are expected to be released to US consumers early this year, carriers are still upgrading their networks. There will probably be pockets of service in the US this year but widespread network build-out and adoption by consumers and businesses is expected to take years.

In Australia, Optus and Telstra successfully tested 5G on the Gold Coast in August last year and announced commercial rollout this year, Deloitte says.

Smart-home devices from speakers to home assistants and connected refrigerators offer the ability to relay the weather or guide consumers through recipes, tasks that until recently had fallen to smartphones.

Michael Woods, 32, a federal government lawyer in Washington, DC, says his new year’s resolution is to reduce his screen time, something his two Amazon Echos and Google Home hub help him with. “Not because I want to get rid of my phone but just because I want to be more present,” he says.

The breadth of connected gadgets has made it harder to unplug. But the more nascent additions tug on people’s attention differently than smartphones, a potential allure for people irritated by the flurry of notifications from their phones, says Kai Lukoff, a researcher at the University of Washington who is studying problematic smartphone use. “With a smart speaker, it only responds to requests I make of it,” Lukoff says.

A growing number of children have smartphones but those devices are no longer the only avenue to private social interaction for children and tweens, many of whom enjoy their own tablets and gaming systems complete with headsets that allow them to talk regularly with friends without a phone.

Device makers will have to prove that they can emerge from what some consumers see as years of marginal improvements in camera, battery and security functionality.

Rick Berkowitz, 65, of St Louis, Missouri, uses his new iPhone XR to monitor stocks, cast yoga videos on to his TV and FaceTime his grandchildren. But the features, other than unlocking his device with facial recognition, leave him unimpressed.

“I personally believe that all these phones have pretty much reached their zenith just like the PCs did,” says Berkowitz, who runs his own hedge fund.

The challenge that tech companies, wireless carriers and device makers face is launching the next society-shifting technology.

“What’s not going to go away: the need to have a device that’s constantly with you, to remote control your life. At the moment we call that the smartphone,” says Jaede Tan, a regional director at App Annie, which tracks smartphone behaviour. “Does it become smaller, sit on your wrist, a chip in the back of your mouth? Maybe. The concept needs to remain constant.”

The Wall Street Journal