Religious discrimination can create unhappy business, legal battles

Religious discrimination can create an unhappy business and land you in expensive legal battles.

French oil giant Total recently sent its 96,000 employees an unusual corporate missive: a comprehensive guide to religion at work.

Intended as a practical tool for managers and employees, its 80-plus pages cover everything from the basic tenets of major world religions to whether bosses must provide halal food during company meals.

Few companies have gone as far as Total, but religious issues are cropping up more often in the workplace, resulting in lawsuits and complicated questions of faith on the job.

With many managers encouraging employees to “bring their whole selves to work” and celebrate their individual identities, religious identity has proved tougher to navigate, managers and experts say.

When it comes to faith, most companies “stay as far away as they can” for fear of making a wrong — or unlawful — move, says Deb Dagit, former chief diversity officer at drug maker Merck. Dagit now runs her own consulting group.

Religious discrimination complaints filed with the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission increased by 50 per cent from 2006 to last year. While religious discrimination comprises a relatively small portion of EEOC complaints, the rise reflects an ever more multicultural workforce with a wider array of religious faiths, says Mark Fowler, deputy chief executive of Tanenbaum, a not-for-profit organisation that works to eliminate religious prejudice.

At 92 pages, the English-language version of Total’s guide offers few firm rules but states employees’ religious practices, such as prayer, should generally be respected and accommodated. Total’s employees aren’t required to read the document, which is available to those who are “curious”, a company spokeswoman says. The company created the guide to help managers and employees who “may have questions or doubts on this topic, working with people who might not eat, dress or pray the same”, she says.

US companies often fail to address employee faith until problems arise, Philadelphia-based employment lawyer Jonathan Segal, of law firm Duane Morris, says. US companies cannot ban religious expression outright and US laws require employers to accommodate religious expression as long as it doesn’t cause undue hardship on the company or workforce.

“Employees don’t shed their religious rights when they walk in the door,” Segal says. “It’s a balance.” For instance, he says, a receptionist’s request to keep a Bible at the front desk may be treated differently from an employee’s request to keep one in an office, away from public view.

Failing to strike that balance can put companies into hot water.

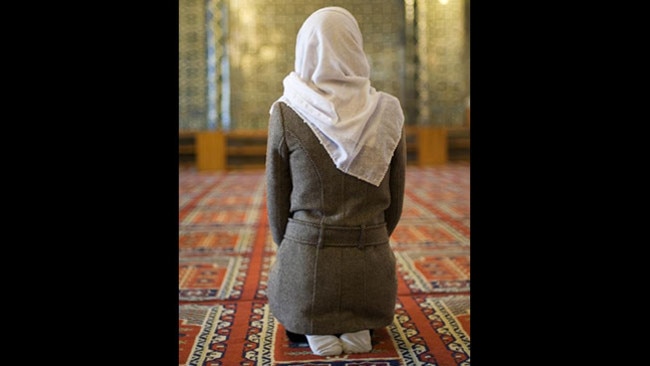

After turning down a Muslim job applicant because her headscarf violated dress codes for retail employees, American clothing store chain Abercrombie & Fitch lost a discrimination case that went to the US Supreme Court in 2015. In a statement, Abercrombie says it has “granted numerous religious accommodations when requested, including hijabs” and “remains focused on ensuring the company has an open-minded and tolerant workplace environment for all current and future store associates”.

In December 2015, Cargill fired more than 100 Muslim workers from a meat packing plant in Fort Morgan, Colorado, in the midst of a dispute over whether they could take prayer breaks at work.

The workers, mostly from Somalia, filed complaints with the EEOC and were deemed eligible for unemployment benefits by Colorado’s Labour Department last year. At the time, the Council of American-Islamic Relations said the company had told workers prayer breaks were no longer allowed, while a Cargill spokesman said no changes had been made to the company’s religious accommodation policies.

Tensions are being felt across the spectrum of faiths. A 2013 Tanenbaum survey of 2024 workers showed white evangelicals were equally as likely as non-Christians to say they felt their faiths weren’t respected at work, and 28 per cent of workers said discrimination against Christians was as serious an issue as discrimination against religious minorities.

The two easiest accommodations companies can make, according to Fowler, are allowances for Sabbath observances or religious holidays and providing kosher, halal or vegetarian options at company-sponsored events.

Religion is often missing from conversations about corporate diversity policies, Dagit says. During her time at Merck, the company began faith-based employee resource groups and educated employees on religious traditions. Even small things, such as celebrating holidays including Hanukkah and Kwanzaa, help workers feel more included, she says.

Tanenbaum’s survey found workers at companies with religious non-discrimination policies were less likely to say they were seeking a new job. And those with access to flexible hours for religious observance were more than twice as likely to say they looked forward to coming to work.

Every afternoon, Nazneen Nathani, an associate manager at consulting firm Accenture, stops in a designated prayer room in her Los Angeles office. A Shi’ite Muslim, she prays up to five times daily but just once at the office.

“It’s not an easy time to be a Muslim in America,” says Nathani, a 14-year company veteran who works in risk management and quality. The accommodations “show me that I’m valued, and not just for my contributions as an employee, but also for who I am underneath all of that”.

Additional reporting: Neanda Salvaterra

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL