British economy will feel Brexit plan for many years

Beneath the surface of the Brexit political storm, there are harbingers of economic costs to come.

The British economy has so far weathered the political storm surrounding Brexit pretty well. But beneath the surface, there are harbingers of economic costs to come.

Researchers at the Centre for European Reform, a London think tank focused on European Union policy, estimate the economy was 2.5 per cent smaller at the end of the second quarter than it would have been had voters chosen in 2016 to stay in the EU.

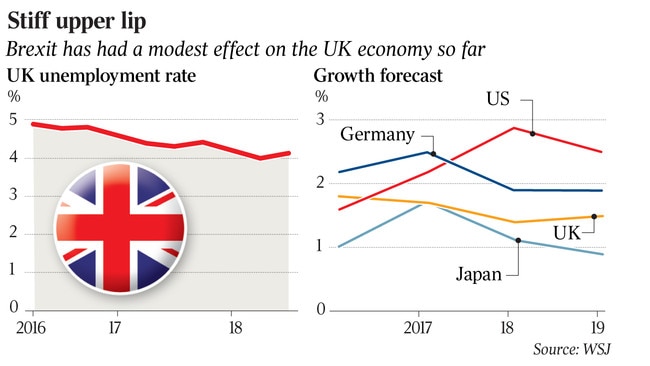

Growth in the UK slowed after the referendum as economies such as the US, France and Germany kicked into higher gear, a reflection of subdued investment and a squeeze on consumer wallets from a burst of inflation. In 2017, only Italy turned in a weaker performance among Group of Seven economies.

Investors are wary. In dollar terms, the FTSE 250, a better barometer of domestic companies than the globally focused FTSE 100, is down 8 per cent since Britons voted to leave the EU in 2016. France’s main index is up 12 per cent over the same period, and Germany’s has gained 10 per cent.

Still, the unemployment rate in Britain is close to a record low, while wage growth has at its fastest pace in a decade. A once-yawning trade deficit has shrunk. A persistent budget shortfall has been whittled down through years of belt-tightening, allowing Treasury chief Philip Hammond to cut taxes and pump extra cash into hospitals. The Bank of England is gently nudging up borrowing costs. While Germany’s economy contracted in the third quarter, the UK’s expanded at a 2.5 per cent annual rate.

All are signs of an economy making steady, if unspectacular, progress after the long climb out of post-financial-crisis doldrums — with less progress than might have been expected had the Brexit referendum gone the other way. “We are in a reasonably healthy place,” said Peter Dixon, senior economist at Commerzbank in London.

The economy’s future prospects hinge on the shape of the Brexit deal Prime Minister Theresa May is able to negotiate with the EU. A draft agreement between London and Brussels over the terms of Britain’s withdrawal, which didn’t cover in detail its future economic ties to the EU, sparked a fresh bout of political turmoil in London last week and new doubts about whether Mrs May can get her plan through parliament. She faces opposition from Brexit supporters who want a cleaner break with the EU and pro-EU lawmakers who want closer ties. Mrs May’s domestic travails mean an abrupt and messy break with the EU when the clock runs down on Brexit talks in March remains a real possibility. Such an outcome would leave the UK facing significant tariffs and regulatory hurdles with a bloc that accounts for half its trade.

The short-term consequences could include severe disruption to everyday economic activity when the UK exits the EU’s legal regime. Lawmakers worry ports might gum up or flights may get cancelled. Central-bank officials warn of an economic shock akin to the oil crises of the 1970s or, ironically, the blow to New Zealand in 1973 when the UK joined what would become the EU, undermining New Zealand’s position in its major export market.

Longer-term, a no-deal scenario would leave the British economy as much as 8 per cent smaller by 2030 than it would have been had Brexit not happened, the International Monetary Fund estimates.

Yet even if Brexit goes smoothly, the consequences for the British economy are broad and deep, with early tremors already felt. Economists believe Brexit has hurt the UK’s capacity to produce goods and services without stoking inflation. The BOE estimates the economy’s speed limit has dwindled to around 1.5 per cent a year, from a historical rate closer to 2.5 per cent.

BOE governor Mark Carney has described Brexit as a process of economic adjustment that will play out for years to come, as companies reorder supply chains and find new customers outside the EU. Whole industries could shrink, while others expand, economists say, as the economy slowly adapts to post-Brexit trading relationships.

Such a shift has knock-on effects for productivity. Productivity growth in the UK is weak relative to other advanced economies, and that long Brexit reorientation could weigh on it further by crimping trade and investment.

“We are unravelling relationships we’ve had for 40 years,” said David Owen, chief European economist at Jefferies. “Ripping it up and moving on — it’s going to take years.”