Brands look to daigou in Australia to boost China sales

Unilever wants its Aussie instant-soup brand to be a hit in China. So it is offering free samples to Chinese residents in Australia.

Unilever wants its Australian instant-soup brand to be a top-seller in the lucrative Chinese market. But instead of launching an advertising campaign in Beijing, it is offering free samples to Chinese residents in Australia, hoping they will buy and ship the product to family, friends and other consumers back home.

The Chinese buyers in Australia are called “daigou”, a term (pronounced “die-go”) derived from a Mandarin phrase that means “buying on behalf of”. That role has evolved from students or tourists who sent home the occasional package to people who do it as a part-time or full-time job, reaping often hefty profit margins.

Now, companies like Unilever are increasingly marketing their products directly to daigou, a low-cost channel into the Chinese market that doesn’t require warehouses or distribution networks in China itself. But even well-known Western brands, many of which are still absent from China, aren’t guaranteed success, and must convince daigou and their Chinese customers that their products are high-quality and authentic.

“The daigou buyers here have become more like a wholesaler,” said Julia Illera, a consultant at market-research firm Euromonitor International in Sydney. They could “make or destroy a brand” in China, she said.

Daigou sales are difficult to measure because the items can be bought routinely from grocery stores and pharmacies. But such sales could exceed $1 billion annually, according to an estimate from Keong Chan, executive chairman of AuMake International, which operates stores in Australia that cater specifically to Chinese tourists and daigou.

Marketing to daigou could be more effective at first than a conventional advertising campaign in China. Chinese consumers are willing to pay more for products they know are shipped directly from overseas because of concerns over locally made products as a result of scandals such as the 2008 tainted-milk incident. And they rely on daigou for information on which products are popular abroad.

After the milk scandal, Australian supermarkets restricted the amount of infant formula that individual customers could buy because the demand became so intense. Other popular daigou items include dietary supplements, cosmetics, Ugg boots and jackets.

The stakes are high. After an oversupply of products from infant-formula producer Bellamy’s Australia in China forced Chinese e-commerce sites to lower prices, daigou in Australia struggled to make a profit on Bellamy’s products, and many switched to other brands.

That dented the company’s margins, and in December 2016 Bellamy’s shares crumbled by almost 50 per cent, and the chief executive eventually resigned.

“Bellamy’s inadvertently went too broad on distribution, which led to crowding out of the daigou channel,” a Bellamy’s spokesman said, adding that the surrogate buyers were now “back as core to the business”.

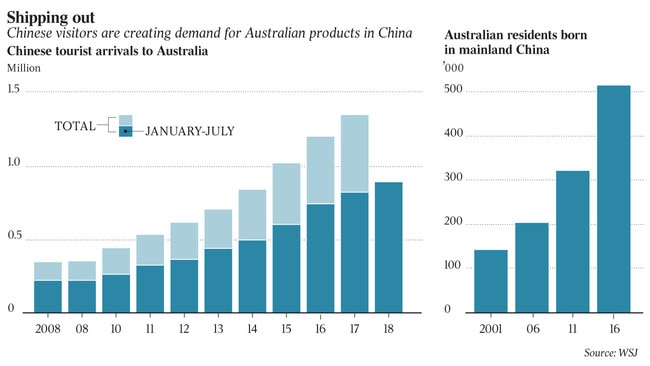

Daigou operate all over the globe, but Australia is a focus given the influx of Chinese tourists and students in recent years. The country received more than 1.3 million Chinese visitors last year, up 12 per cent on the previous year, according to Australia’s tourism agency. And about 510,000 mainland China natives live in Australia, according to the 2016 census, up 60 per cent from 2011.

Earlier this year, Mr Chan’s company, AuMake, opened a store in Sydney that it calls a “daigou hub”, where an assortment of products can be bought and shipped out to China from within the store. It also includes a cafe and a room where Australian companies, such as cosmetics company Jurlique, offer training sessions and free samples.

“I find now that we’re able to present in Mandarin, that they’re a lot more engaged,” said Rachael Lupton, regional business manager at Jurlique, whose Mandarin-speaking colleague gave a presentation at AuMake’s store about a new product line.

Two audience members were using smartphones to film video probably intended for online viewing by customers back in China. At one point, the daigou lined up to take photos of themselves with the Jurlique employees. Among them was Winnie Qian, 23, a student who shops mainly for her parents and grandparents back in China but wants to expand her daigou business.

“I have to make my customers trust me,” she said. The photo, which she planned to post on the popular Chinese messaging app WeChat, shows that “we’re buying the real Jurlique, and we really understand the product,” she said. “We just want to show the customer that we’re here.”

Currently, some personal shipments under a particular value weren’t taxed by Chinese authorities, said Matt McDougall, whose Sydney-based company, DaigouSales, operates an online store for daigou. A new Chinese e-commerce law, however, goes into effect next year. Mr McDougall doesn’t expect it will significantly affect daigou shipments at this point, though the taxes could rise.