Advertisers take on Google, Facebook

In the past year and a half, Facebook and Google have had one run-in after another with advertisers.

Add to the list of people frustrated with Facebook and Google a quiet but hugely influential group — the people who pay the bills.

In the past year and a half, the two firms have had one run-in after another with advertisers.

Procter & Gamble was among many companies that boycotted Google’s YouTube when it discovered ads were running before extremist and racist videos.

Marketers pushed Facebook to provide more credible data about how many people actually view ads on its platforms, after the social giant acknowledged mistakes in its numbers. Now there’s the revelation that data on tens of millions of Facebook users were improperly accessed by Cambridge Analytica, a firm tied to Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. That has sparked anxiety among some marketers, including over whether their own data on Facebook is safe.

Madison Avenue’s increasing uneasiness with the platforms and its moves to push back aggressively are fundamentally reshaping the relationship. Advertisers’ broad push for changes has played out in behind-the-scenes dust-ups, veiled and overt threats and advertising boycotts, and has extracted some concessions from the tech giants. Among the leaders is P&G, the world’s largest advertiser.

Many companies are actively policing their ad purchases to ensure they avoid objectionable or irrelevant content. Some are cutting budgets. And they are demanding far more transparency from Google and Facebook about the performance of their ad campaigns to make sure they aren’t wasting money.

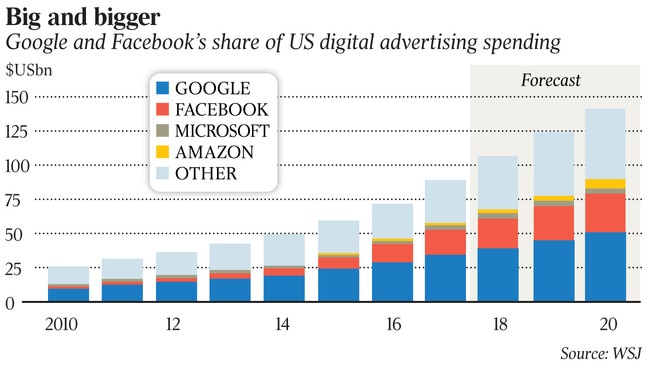

Advertisers have poured huge sums into the two tech giants over the past decade, lured by their huge audiences and ability to target ads based on reams of consumer data. Facebook and Alphabet’s Google are known in the industry as a “duopoly”, with overwhelming dominance of the US digital ad marketplace, which is expected to reach $US107 billion ($138.6bn) this year.

Yet both firms are now on the defensive about the role they played in the 2016 election and on their broader role in society. The latest controversy over the mishandling of Facebook user data has prompted a handful of small advertisers, including wireless speaker company Sonos and auto-parts chain Pep Boys, to temporarily suspend spending on the platform. Some advertisers want to ensure the data they upload to Facebook on their customers — a tactic used to target ads at their desired audiences — are protected. And they are watching to see if the scandal reduces Facebook’s use by consumers. Facebook has moved to reassure top ad executives in recent days.

P&G said it was poised to return to YouTube on much stricter terms. It will hand-pick a list of acceptable channels to advertise on rather than relying solely on Google’s algorithm, which tries to match viewers with the advertiser’s target audience.

“We realised we can’t count on them. We have to take this into our own hands,” P&G chief brand officer Marc Pritchard said.

P&G this month said it cut more than $US200 million in digital ad spending in 2017, including 20-50 per cent cuts at “several big digital players”, partly because better data showed it was wasting money. P&G found that the average view time for a mobile ad appearing in the news feed on platforms such as Facebook is only 1.7 seconds.

Restaurant chain Subway plans to cut back on Facebook spending this year and one global beverage company is planning to cut its spending on Facebook ads by about 30 per cent in the US and the UK this year.

So far, there’s no sign of financial damage to the tech companies, and they remain in a commanding position. Last year, Facebook totalled $US39.9bn in global ad revenue, up 49 per cent from a year earlier, and the YouTube controversy didn’t appear to make a dent at Google, where ad revenue grew 20 per cent to $US95bn.

“They made a lot of changes, and that is a good thing,” P&G’s Mr Pritchard said. But Facebook and Google are insulated when any advertiser, even a big one, pulls spending, given how many they work with. “At the end of the day, do they really need us?”

The latest data from research firm eMarketer showed Google and Facebook’s combined US digital ad market share will drop for the first time this year to 56.8 per cent, from 58.5 per cent last year. No other digital player is expected to top 5 per cent this year, including Microsoft, Verizon Communications and Amazon.

P&G’s pushback began more than two years ago. In February 2016, Mr Pritchard went to Silicon Valley and met with executives from tech companies including Facebook and Google to complain about what he saw as a declining return on investment from digital ads.

Mr Pritchard wanted to know if ads were hitting the right target and how long they were being viewed, and he wanted the platforms’ data to be verified by an accredited independent third party, similar to the role Nielsen plays in television ratings, sources said.

During a tense session at Google’s Mountain View, California, headquarters, Google’s chief business officer, Philipp Schindler, told Mr Pritchard that P&G’s rivals were spending billions of dollars without getting accredited third-party measurement data. Mr Pritchard told Mr Schindler that P&G would stop spending if Google didn’t step up. “Hundreds of millions of dollars may not seem like a lot to you, but it’s a lot to us,” Mr Pritchard said.

Several months later, it was Facebook’s turn to take the heat. In August 2016, the company disclosed in a post on its “Advertiser Help Centre” that its metric for the average time users spend watching videos was artificially inflated, because it was only counting views of more than three seconds.

Facebook told advertising giant Publicis Groupe that average video viewing time was probably overestimated by 60-80 per cent. Other miscues followed. Facebook fixed the problems as they arose and said they did not affect billing, but trust with advertisers had frayed.

“The days of giving digital a pass are over — it’s time to grow up,” Mr Pritchard said publicly at an industry trade group meeting in January last year.

The following month, at a meeting of the Association of National Advertisers, the group wanted to know when Google and Facebook would allow the industry’s measurement watchdog, the Media Rating Council, to audit some of their metrics.

Instead, Facebook executives including Carolyn Everson, vice-president for global marketing solutions, launched into a presentation about how video ads were effective on Facebook, even if users only watched them for a very short time, said people familiar with the meeting, frustrating some attendees.

“If our boards come to us and ask us, ‘Do you know where these dollars went’ and we cannot confirm it, we have a problem and therefore you do,” said Deborah Wahl, who was then US marketing chief of McDonald’s, according to one of those people.