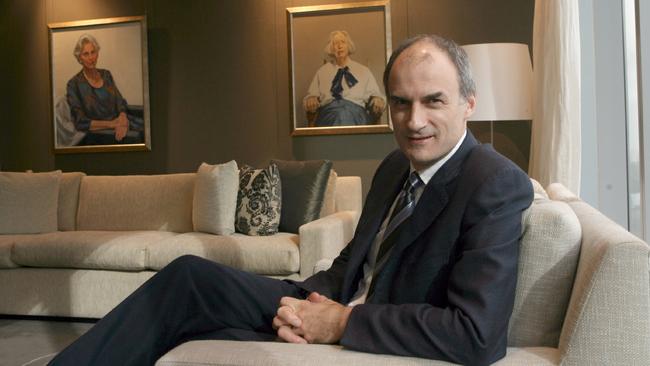

Time for biotechs to take off, says Peter Doherty Institute chair Martyn Myer

The scientific journey has many pitfalls and commercial development can be painfully slow, but that’s no reason to think small, says Martyn Myer.

Martyn Myer knows a thing or two about Melbourne – his family’s name is on landmarks from Bourke St to Kings Domain – but he can’t understand why the city isn’t home to more biotechnology companies.

After all, it was in Melbourne where CSL was established in the upheaval of World War I, and it has since become the world’s third-biggest biotech. When Australia applies itself, it punches well above its weight.

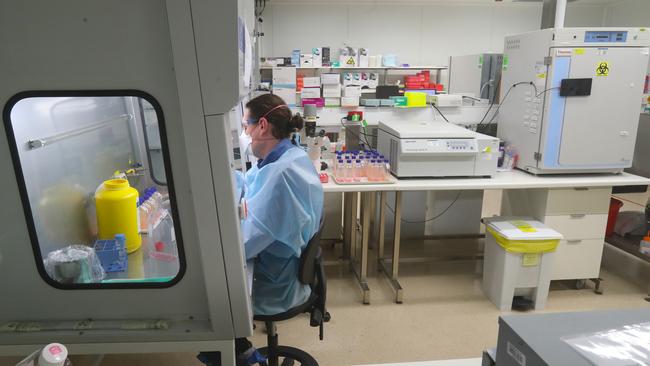

And it is this mindset he is bringing to his new role as chair of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity – a partnership between the University of Melbourne and Royal Melbourne Hospital that grew the first sample of Covid-19 in cell culture outside China.

Mr Myer knows the sector well. For the past 22 years, Mr Myer has chaired ASX-listed neuroscience company CogState, which has a market value of about $327m and has focused on treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.

“I understand the pitfalls of the scientific journey and the sometimes frustrating pace for commercial development. But nevertheless, I also understand that Australia has never done enough to commercialise its terrific medical research,” he said.

“I mean, we have some good examples, but for a country of our size – if you think of Switzerland or Sweden, which are smaller than us, and they have great companies in the space – I tell anybody who will listen we should have 100 CogStates in and around Parkville.

“If I could add real value, it would be to help this (Doherty) institute and this centre to commercialisation because that’s where financial sustainability is – it adds to the virtuous loop. If we had some wins commercially and that started to produce income, we’re off to the races.”

Those wins would also draw more money into the sector, which has traditionally struggled to attract investors in Australia given the glacial pace of clinical development and the perceived low success rates.

“It’s a cultural thing,” Mr Myer said.

“We’re moving in the right direction. There’s more venture capital funding. There have been enough examples to demonstrate that you can have serious commercial success – CSL is the obvious one.

“But it’s going to take quite a long time for, if you like, the financial market, the commercial market to really accept that this is normal and you do have to invest significantly. You don’t get a lot of wins but when you do get a win it’s usually very big.”

On this score, he said Australia’s universities and research institutes were becoming more sophisticated at protecting and developing their intellectual property, setting themselves up for a better chance of commercial success.

“When I joined the board of the Florey Institute 30 years ago, we had a very naive view of what protecting IP was about – going all the way back to Lord Florey himself,” Mr Myer said, referring to Australian pharmacologist Howard Florey who shared a Nobel prize in 1945 for his role in developing penicillin.

“He never patented penicillin. If he had, Oxford University would be the wealthiest university on earth. Imagine if they owned all the patents for antibiotics. But he had this naive view that it was public money that funded it, therefore you don’t have to protect it, you give away the IP.

“Lilly as a pharma company (which has a market value of $534bn) built itself in World War II off the value of that patent.”

Government policy settings are also becoming more appealing, encouraging biotechnology companies to produce their IP in Australia rather than overseas.

CSL has invested $1bn in a new plasma fractionation plant in Melbourne’s north. It’s a massive turnaround from eight years ago, when it told a Senate inquiry that “Australia is a relatively unattractive location for entrepreneurial manufacturing or as a base from which to commercialise locally developed intellectual property into global markets”.

“My skills, as an engineer, are to bring complex projects and initiatives together – that means working with lots of stakeholders with perhaps conflicting aims, helping motivate big donors to cough up to a big vision,” Mr Myer said.

“My engineering skills can be applied in helping manage the construction of complex buildings and so on.”

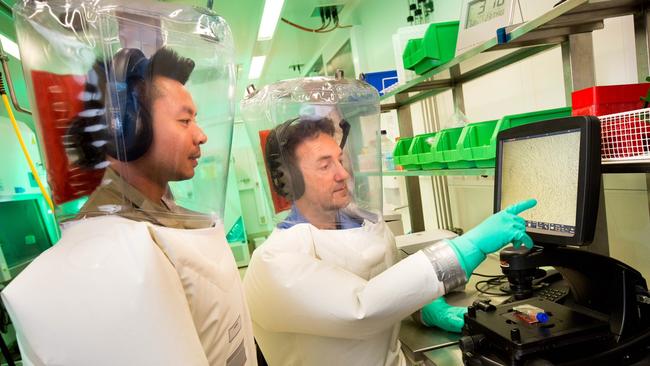

Mr Myer’s appointment to the Doherty Institute comes as it establishes the Cumming Centre – named after Canadian oil and gas mogul Geoffrey Cumming, who donated $250m towards its development – to accelerate its research and development of therapeutics for Covid-19.

It followed a report from Boston Consulting Group that revealed $137bn had been spent on Covid-19 vaccine development, versus $7bn on antiviral therapeutics as of October last year.

Institute director Sharon Lewin said the rapid development of therapeutics, as well as lowering the cost, was crucial in future pandemic preparedness.

“I have spent my life, and still do, working in HIV where we don’t have a vaccine after 40 years of massive investment, but we have got fantastic antiviral therapeutics, we’ve totally turned around the HIV pandemic,” Professor Lewin said.

“And so therapeutics, many antivirals not only can treat some of that’s infected, they can protect you from becoming infected. So you need both. Vaccines are much cheaper and a much easier way to manage a pandemic but then sometimes you can, sometimes you can’t develop one. If you had a really good therapeutic and antiviral that was super-cheap and had no side effects and you could take before you hopped on a plane and went overseas, just like you take an antimalarial tablet – we are nowhere near having that now. That is the gap.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout