They’re young, ambitious and have their own ideas about how a workforce should be run

People born between 1996 and 2010 now make up one third of the workforce and some have already climbed the corporate ladder. Here’s how they do things differently.

A dramatic shift is silently playing out across the nation as a new generation of workers climbs the corporate ladder.

Generation Z, the cohort born between 1996 and 2010, now make up a third of the entire working population.

This generation now has more workers in their 20s than teenage years, and as they enter the workforce they’re bringing with them a raft of changes that management are having to navigate.

Different attitudes towards work and a strong preference for who they work for are just a handful of things employers are having to manage. But in some cases the script is being flipped, with an entrepreneurial few from the cohort having already made their way into management, or even founded their own businesses.

Here’s how Gen Z bosses view the workforce and what they are doing differently from their predecessors.

At just 28, Danielle George has nearly a decade of experience in the healthcare industry. The ambitious critical nurse began working as an assistant and NDIS worker when she was just 18.

In 2017, while studying nursing at the University of Sydney, she was approached by a friend of friend who wanted someone with inside knowledge of the healthcare industry. Four years later, while she was working as a nurse inside an emergency ward, Ms George finally moved over, joining LunaCare as a partner and its head of client care.

Ms George was the first employee. Today, the start-up, a registered NDIS provider, has about 100 staff on casual contracts under her wing.

LunaCare provides care including in-home visits to patients across NSW and the ACT and has plans to expand across Australia.

Her view on managing younger teams is that it’s crucial to consider the impacts of the job on their personal wellbeing.

“Nursing is an industry where burnout is very real for an employee … you’re dealing with people on their very worst days,” she said. “What I’ve experienced has been the brunt of it during exceptional times during Covid and working in emergency wards.”

It’s also important to reward staff to keep morale up and provide generous incentives. “When I was a nurse, I got a pen and coffee cup as our Christmas thank you,” she said. “(At LunaCare) we pay well above award rates, and offer a lot of incentives. Staff are regularly taken out for dinners, invited to bonding sessions including axe throwing, and given access to referral schemes.”

Grace Brown, a Melbourne-based roboticist, has a similar view. The 24-year-old founder and chief executive of Adromeda, a start-up building robotic companions, told The Weekend Australian employee bonding sessions and regular events were crucial to keeping staff engaged. They also boosted productivity.

“If you just do work together and you just put your head down and work and work, you kind of can lose touch with the humanness of working with people,” she said. “You just have to go out for lunch together or do some sort of fun activity together every couple weeks … it really boosts productivity.”

Andromeda has raised about $3m in capital and has in the past 12 months picked up commercial contracts with revenue exceeding that amount. By mid-2025, it will have about 50 companion robots in the market, mostly at aged care homes.

Ms Brown has a strategy she believes has helped Andromeda’s rapid growth.

“My philosophy with running a company is that I prioritise my team, my customers and my investors – in that order,” she said.

“You have to prioritise your team first because everything starts and ends with your team. If your team’s working well together, you’ll be delivering better value to your customers. And if you’re delivering great value to your customers, your investors should have nothing to really complain about.”

Ms Brown isn’t as gung-ho on the work-from-home era as most assume about Gen Z.

“It’s a little bit hard to build a robot remotely,” she said. “That’s one thing that’s a bit different about our business compared to probably a lot of other businesses that are software based.”

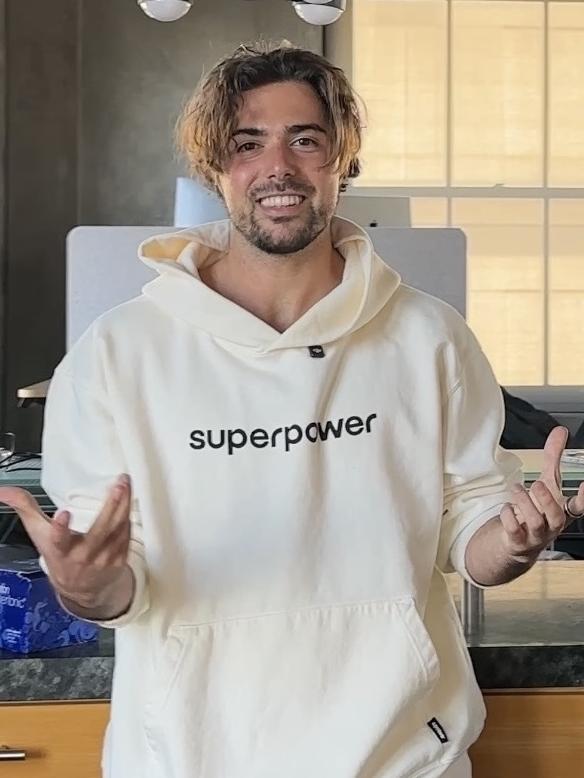

Max Marchione is just 24 and yet for the past two years he has helped build what’s now a $250m start-up playing in the longevity space. Longevity, or preventive healthcare, is designed to help improve ageing.

The niche and upcoming type of care was once a privilege reserved for the wealthy but it is increasingly being commercialised with modern technology.

But for Mr Marchione, who co-founded Superpower in 2023, the issue is personal, having faced a series of complex illnesses from the age of 10 to 18.

Superpower provides a boutique health service, beginning with a series of tests followed by specialist clinical advice and care, beginning at $US500 ($810).

Mr Marchione, who is chief commercial officer, oversees operations of the start-up and its 59 staff. “Gen Z just want to work on things they care about, the things which matter (to them).” he said.

Another important concept was transparency. “Gen Z grew up in a world where everything was online.” Mr Marchione said. “We believe in this principle of radical transparency and what that means is internally, we share everything with the team.

His generation also doesn’t care for professionalism or hierarchy. “I think that it’s way more like fun, casual and less professional. The next thing is there are far less hierarchies. We tried to be obsessively as flat as possible. We want people working collaboratively versus up and down.

“We don’t like the idea of management, so to speak … even when we make promotions, we’ll call them ‘team changes’.”

Jahin Tanvir was one of the few Australians to leave the pandemic in a different career to when he started. He wanted to start a business teaching public speaking and seminars so he jumped on TikTok in 2021 and began making videos. Within months he’d begun teaching seminars at the likes of the Commonwealth Bank, Toyota and Canva.

The following year his business, Breathe, was acquired by the Australian School of Entrepreneurship, and he became CEO.

One way he kept younger workers engaged was to prove to them why the job was important.

“Young people especially, they don’t want to do something because they’re supporting a massive corporation,” he said.

“No young person wants to be in a role where they’re not growing or learning and these days, young people have almost too many options for work,” he said.

“If a role isn’t working, they’ll leave in six months. Whereas my parents would have been stuck in a role for 12-15 years because there’s a bit of loyalty there.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout