World’s biggest music company deploys the ‘nuclear option’ against TikTok

Universal’s showdown with the platform is testing the value of the seconds-long song snippet — and who has the most power in today’s music economy

Gwen Stefani wanted her new song to have its day.

The No Doubt frontwoman and star solo artist planned to release a duet with husband Blake Shelton earlier this month and promote it with a pre-Super Bowl performance. A week before the release of “Purple Irises, ” however, her label’s parent company, Universal Music Group, took the unusual step of pulling all of its artists’ songs off TikTok after reaching a stalemate in contract negotiations with the social-media platform.

The move meant that Stefani’s song couldn’t be released on TikTok and short videos promoting it on the app — a ritual that has become a core element of marketing new music releases — were a no-go.

Stefani and her team decided to pivot: Shelton’s country label, Warner Music Nashville, distributed the song instead of Universal’s Interscope Records. “Purple Irises” has since racked up millions of views on several TikTok videos Stefani and Shelton made featuring the tune.

The companies are battling over how much TikTok pays Universal — the world’s largest music company — to make the label’s vast catalogue of songs available to one billion-plus social-media users worldwide, who are eager to splice snippets of that music into their dance videos, tutorials and memes.

They are negotiating in a new world in which a seconds-long clip of a song on TikTok can be just as valuable as the tune in its entirety.

The fight escalated this week, with Universal bringing on what many in the industry call “the nuclear option” — requiring TikTok to take down songs on which any songwriter signed to Universal’s publishing division has a credit.

TikTok said it started doing that late Monday to ensure all such tracks are removed by the end of the month.

The move could affect 80% of the current hits across Universal, Warner Music Group, Sony Music Group and independent labels, by some estimates. Since a top hit can have more than 10 songwriters involved from multiple publishers, even if one songwriter of many on a track is signed to Universal, it will have to come down.

TikTok estimated a lower percentage would be affected, saying 20% to 30% of popular songs used on TikTok would be silenced, depending on the market. TikTok reached out to Universal in recent days with a proposal the music company felt didn’t meaningfully address its concerns on compensation, platform safety or artificial-intelligence protections, according to people close to the negotiations, and discussions haven’t progressed.

The broader take-downs rope every major music company in the world into Universal’s conflict with TikTok. While the move will limit the reach of millions of songs in the near term, if Universal is able to elicit more favourable economics from TikTok, rivals could press for improvements to their terms the next time they renegotiate their deals with the social-media platform.

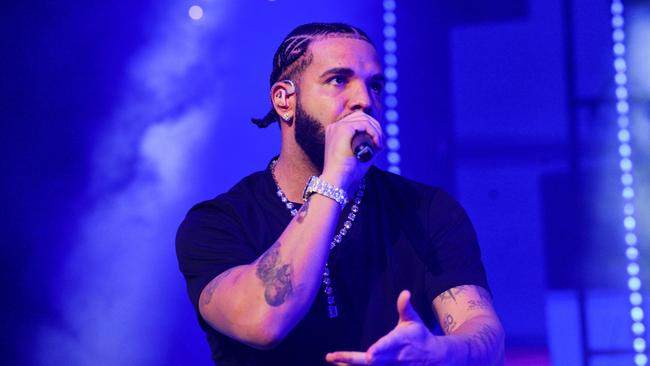

The showdown is putting to the test which company has more leverage in the streaming era: a Chinese-owned social-media giant with an app on nearly every Gen Z and millennial phone, or the label behind Taylor Swift, Drake and Billie Eilish. After years of offering TikTok discounted terms, Universal wants TikTok to start paying royalties in a longer-term deal, the way other established video-centric apps including Meta’s Instagram and Google’s YouTube do.

The ongoing feud between one of the world’s biggest music promotion platforms and Universal is reverberating across social media and the recording industry, forcing artists to rethink how they release songs and some TikTok users to change how they engage with the platform.

“Whatever happens here is going to dramatically affect the next several years of global music revenue,” said Bill Werde, director of the Bandier music business program at Syracuse University.

‘Imagine what it sounds like’ Music has become the lifeblood of TikTok. Last year, 85% of videos on the platform contained music, according to content identification technology and data firm Pex, and it’s trending upward.

The snippets of sound — up to 60 seconds in length — that enliven TikToks often help videos go viral, leading to a sharp uptick in streaming full versions of the song on services such as Spotify and Apple Music, driving more revenue to a label and artist.

TikTok videos featuring music by Universal artists went silent on Feb. 1, the day the label’s license expired amid the negotiating stalemate.

Among Universal’s high-profile stars, Ariana Grande recently released a remix of her new song “yes, and?” with Mariah Carey and posted a TikTok earlier this month to promote it.

The video appears to show Grande and Carey singing, but instead of the song playing, the audio is an AI-generated voice saying: “We’re not allowed to put the song here. So watch this video and try to imagine what it sounds like.” Carey, who is a Sony Music artist, and Grande didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Kim Petras, another Universal star whose songs from her latest album were blowing up on TikTok before the take-down, said she supported the move and felt protected by her label.

“Of course, right now, all of us Universal artists are facing challenges, but you’ve gotta take one for the team,” she said. “The intentions behind this initiative are noble, aiming to ensure that musicians are fairly compensated for their art. This extends not only to the chart topping performers but also to the songwriters and individuals working tirelessly behind the scenes.” The record industry has for decades been somewhat beholden to behemoths that purvey its music to customers. In the heyday of CD sales, bricks-and-mortar giants such as Tower Records and Walmart controlled order volume and shelf space.

With the advent of iTunes and digital downloads, Apple de-bundled the album, allowing fans to pay 99 cents to own a specific song, instead of $10 for the whole collection on iTunes and even more on CDs.

Spotify then up-ended the idea of owning music at all, shifting consumers to a subscription model by which they essentially rent access to all of the world’s music. Streaming services such as Spotify pay labels a royalty after 30 seconds of a song has been listened to.

TikTok has now effectively broken down songs, letting users isolate their catchiest parts. Scrolling through videos on the social-media app is a sound-on experience that offers younger generations access to the most popular music in the world, entirely free.

The vast majority of young people ages 16 to 19 use TikTok weekly, according to data tracker Midia Research, and the average person in that age range spends 14 hours weekly watching videos on social video platforms, compared with 12.4 hours streaming music.

Record executives and artists’ teams have struggled to measure the true dollars-and-cents value of TikTok because of the serendipitous nature of a song taking off or not, and the fact that virality in itself doesn’t build an artist’s career and fan base. Few listeners that love a portion of a song on TikTok go on to listen to the artist’s prior work, music executives said.

TikTok parent ByteDance inherited friendly music licensing agreements via its $1 billion acquisition in 2017 of short-form video platform Musical.ly, which it merged with TikTok the following year. Labels typically offer smaller start-up companies discounted rates to allow them to grow into viable businesses. The companies have said they expected their deals with TikTok to evolve as the platform gained users.

Universal said it is time for its arrangement with TikTok — whose advertising revenue has quadrupled since their last agreement, according to eMarketer — to change. Instead of the short-term deals the social-media platform has typically forged with labels that include lump-sum minimum guaranteed payments, Universal wants to shift to a new longer-term model with royalties based on usage.

The label has benefited handsomely from music discovery on TikTok in the form of its artists’ work reaching new fans and those listeners streaming songs in their entirety elsewhere. But it needs to extract better economic terms from TikTok to ensure future revenue growth, especially as growth in music streaming begins to plateau, industry executives say.

Not doing so could set a harmful precedent for Universal as other social-media platforms’ deals come up for renewal and new entrants come to the market, they said.

TikTok, a free service, makes most of its money from running ads on the platform, and new deals could shackle it with higher content costs at a time when it is already looking for new revenue streams.

The removal of Universal’s publishing catalogue is shedding light on the messy and complicated world of music copyright. The first tranche of tracks removed were recordings produced by artists signed to Universal’s labels. This next tranche involves the songwriters and producers signed to Universal’s publishing division, which manages the copyrights behind the composition — the music and lyrics — of a track.

That means that any tracks released by Universal’s label competitors, including Sony and Warner, that include a Universal songwriter will no longer be fully licensed and must be removed by TikTok.

On Monday, “Texas Hold ‘Em,” the new country music single by Beyoncé, a Sony artist, topped the Billboard Hot 100. It was a celebratory moment for Nima Nasseri, manager for one of the song’s producers, Hit-Boy.

Nasseri, formerly part of a team at Universal that ran viral TikTok campaigns, had eagerly watched the song’s rise as dance videos featuring the tune mushroomed over the past week, propelling it up the chart. On Tuesday, he woke up to the news that TikTok had begun removing songs that count Universal-signed writers such as Hit-Boy among their credits, which meant “Texas Hold ‘Em” would soon come down.

TikTok doesn’t pay well, Nasseri said, but “that’s not the business — the business is discovery.”

Negotiation breakdown At a high-level meeting between TikTok and Universal last spring, executives for both companies agreed that it was time to forge a different type of deal, according to the people close to the negotiations, who described how the talks rolled out. The companies spent much of 2023 working toward a new, longer-term agreement. With their existing deal up in December, the companies struck a one-month extension to hammer out the remaining issues. TikTok and Universal exchanged term sheets almost daily.

But Universal worried that the deal teams were still far apart, and over the holiday break, formulated a contingency plan and began drafting a letter to artists.

By January, deal teams were butting heads on what the label should be paid and other key issues, including the training and use of AI and the language defining the royalty pool from which Universal’s artists are paid.

Universal wanted the royalty money to be used to pay only human artists, while TikTok said the funds should also be distributed to fans who use AI to create their own music via tools on its platform. Music and tech executives alike anticipate a not-far-off future in which fans will use AI tools to easily make both original music and their own iterations of hit tunes.

Universal warned TikTok’s top executives it would take down artists’ work if a deal wasn’t reached.

Universal sees TikTok as one of many short-form video services, such as Instagram Reels, Snapchat Spotlight and YouTube Shorts. Having forged deals with tech giants Meta, Snap and Google over the past half decade that Universal feels fairly compensate it for the use of its music across a wide range of user-generated content products, the label has said there is a precedent for how licensing fees should work.

By Universal’s math, comparable short-form video platforms pay out at about five times the rate of TikTok.

TikTok doesn’t see itself as the same as Reels and Shorts. Executives believe its product is unique and that the song promotion and discovery TikTok provides should be accounted for in the deal.

On Jan. 30 — the Tuesday before the Grammy Awards, a week when the music business had descended on Los Angeles — some key members of TikTok’s music licensing team were scheduled to meet with Universal executives at the label company’s Santa Monica offices.

In a sign that something was amiss, Universal — generally punctual in its responses throughout negotiations — hadn’t returned a term sheet that TikTok sent the previous day summarising its latest position.

Before the meeting could start, Universal published a letter on its website saying TikTok wouldn’t agree to terms to fairly compensate artists for use of their music on the service.

The letter arrived as a surprise to TikTok, with some executives learning from X that Universal was pulling its catalogue from TikTok. The TikTok executives didn’t go to the meeting.

TikTok felt especially slighted by the timing, given its chief executive was slated to testify in front of Congress on Jan. 31.

Since Universal’s music was taken down, TikTok has encouraged creators to post more photo content by suggesting they will get more likes and comments if they do. “Photo posts get 1.9x more likes and 2.9x more comments on average than videos,” said one notification sent to creators Feb. 12 and viewed by The Wall Street Journal.

TikTok said Monday it hasn’t seen a decline in engagement or lost users since Universal removed its catalogue.

Streaming of Universal artists’ music globally increased slightly in the first three weeks of February — the period post-take-down on TikTok — versus the three weeks prior.

The label has tried to show that it doesn’t need TikTok and is turning to other social-media platforms instead. After pulling its catalogue, Universal transferred several promotional campaigns to Instagram Reels, including one for Kacey Musgraves. Universal artists Taylor Swift and Olivia Rodrigo both ran promotional campaigns on Snapchat in recent weeks.

Some emerging artists have said they are missing out on a critical promotion avenue as they try to break through and find an audience.

Julia Breen, the lead singer of an emerging Connecticut-based indie band called Similar Kind, whose music is distributed through Universal, said she was surprised when her videos went silent. She said she is frustrated that the band won’t be able to promote its coming album on the app because of Universal’s move, or run its usual presale campaign, which helps create buzz ahead of release.

“At this point, it’s hurting us more than it’s helping us,” she said.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout