While Britain celebrated the 70th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s accession to the throne, the longest reign in the nation’s history, Boris Johnson was battling to avoid becoming her second-shortest-serving prime minister.

The fickleness of British politics is legendary. Tenure at the top of the greasy pole can be as slippery and unstable as the ascent — and the slide down is quick and painful.

Less than three months after leading the British to victory over Nazi tyranny in 1945, Winston Churchill was dumped in a landslide election victory for the Labour Party. In 1990, having led the Conservatives to three general election victories Margaret Thatcher was ousted by her own parliamentary colleagues.

Johnson likes to think of himself, improbably, as a worthy heir to those two Conservative giants. Instead, he may face the ignominy of being the shortest-tenured prime minister since Alec Douglas-Home in 1964, whose signal achievement is near-complete historical anonymity.

The fall is a remarkable one. Twenty-six months ago, Johnson led his party to its largest parliamentary majority since the last of those Thatcher victories, in 1987.

His execution of Brexit, after three years in which members of parliament had attempted to annul the referendum to leave the EU, was a master class in sheer political willpower. At the election of December 2019, Johnson secured an 80-seat majority; a rout of the Labour Party’s Marxist agenda and the ouster of its leader; an electoral coalition of the party’s traditional affluent base in southern England with Brexit-backing working-class former Labour voters in the north; and the plausible prospect of a new populist conservatism that could meet the particular economic and cultural challenges of the modern age.

Two years later, members of his own parliamentary party are scheming to force a vote of no confidence.

Johnson’s fall from grace seems all the more puzzling given the proximate cause: an apparent excess of social gatherings. As something of a bon viveur, Johnson has doubtless attended many parties that might have caused him subsequent embarrassment. But the problem with these particular gatherings is not that they were scenes of carnal over-indulgence, but that they occurred at all while Britain was in a Tory government-mandated lockdown during the pandemic.

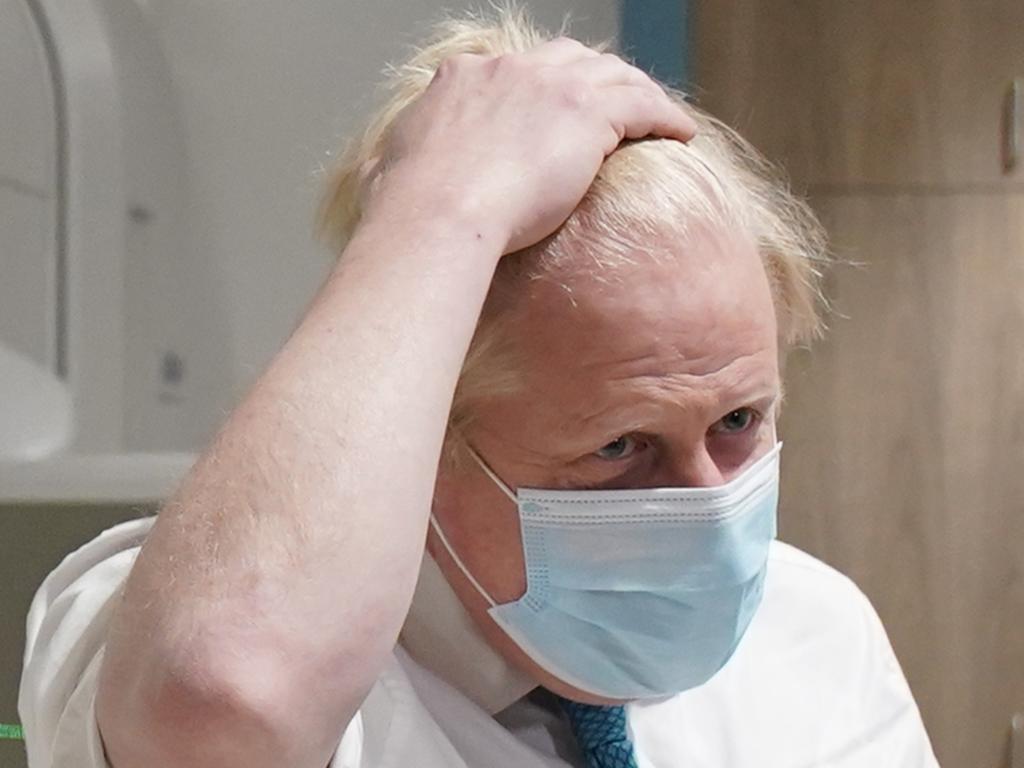

Many Britons made unwilling — but, they were told by Johnson, necessary — sacrifices during lockdowns: observing rules that barred them from attending weddings, baptisms and even dying relatives’ hospital beds. All the while it appears that the No.10 staff, on some occasions including the Prime Minister, were enjoying at least 16 social gatherings on official premises, fuelled by booze. A senior civil servant last week issued a highly critical interim report into the events, and the Metropolitan Police are investigating possible criminal breaches of the lockdown laws.

For all the understandable resentment at the hypocrisy, there still seems something trivial about a prime minister facing the chop over some illicit wine-and-cheese soirees. But the problem is larger than a politician’s hypocrisy.

First, the epidemic of parties reinforces the impression that the Prime Minister is a man of untrustworthy character. For months Johnson has bobbed and weaved his way through questions about the events, offering a series of ever-less-credible attempts to exculpate himself. This reminded people of what they had previously been prepared to overlook — that Johnson has spent a lot of time in a long career dancing between the raindrops of truth and fact. I write this with some cautious self-awareness, but in his days as a British journalist, Johnson was long seen as a skilled practitioner of some of the more notorious habits of that stereotype.

But there’s a larger political problem. It’s not so much that he has lost his way since entering No.10 as that he never really had one. The majority he was given in 2019 was an opportunity to create a meaningful governing agenda from the rhetorical and cultural fragments of national conservative populism.

Two years later, even acknowledging the constraints of the pandemic, there’s nothing to show for it. If anything, the Johnson government seems to have slumped into the embrace of big government, with higher taxes and spending, failing to address the deep economic and cultural divisions that led many people to vote Tory in the first place, and dismaying many conservative members of parliament.

Johnson may survive. His proven capacity for escaping scrapes was best captured by his predecessor David Cameron, who likened him to a “greased piglet”. But Conservatives have an uneasy sense that every day he stays in office represents another day absorbed in the maximal effort to save his own skin.

There may be a lesson for conservatives elsewhere: Hitch your fortunes to a self-absorbed leader of unusual charisma but no consistent political purpose, and be prepared for the inescapable peril that it will always be about him.

The Wall Street Journal

More Coverage