US reluctantly embraces new era of hostage diplomacy

The Griner swap is the latest example of how Democratic and Republican administrations have become more willing to negotiate with foreign governments.

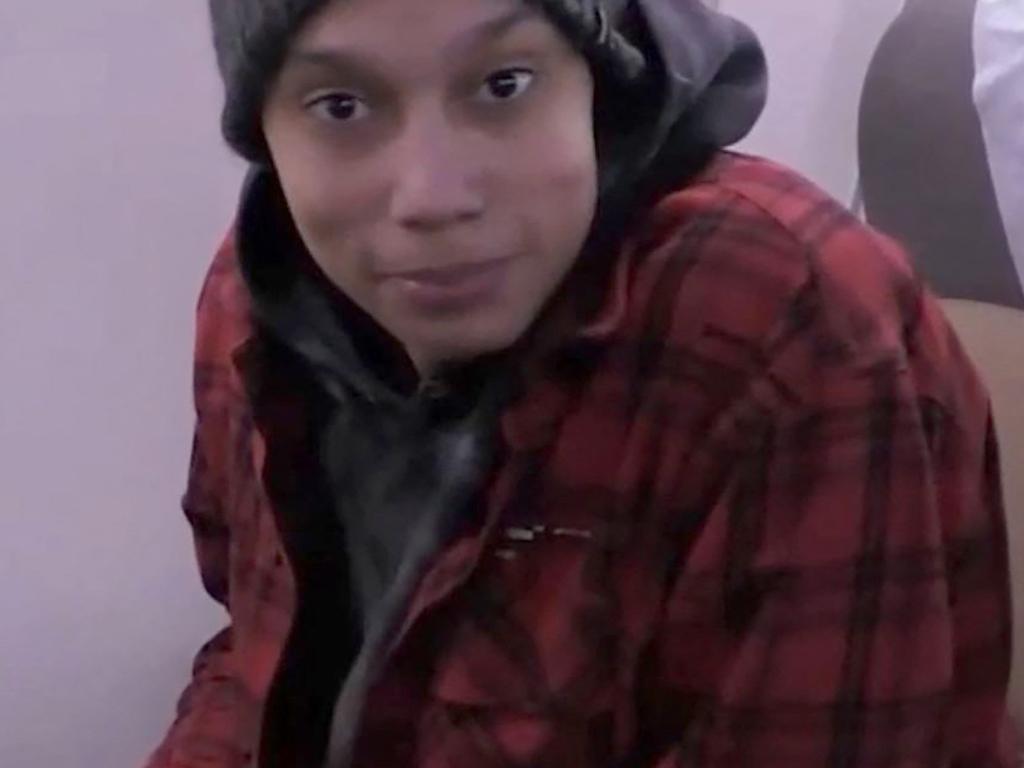

This week’s prisoner exchange that freed American basketball star Brittney Griner brings to at least 12 the number of US citizens and residents who have been freed during the Biden administration in confirmed or apparent prisoner trades.

That number reflects reflect a striking shift: More Americans in recent years have been detained by foreign governments than have been taken captive by terrorist groups or criminal gangs, according to US authorities and private assessments.

In response, the US has become more willing to temper its traditional aversion to negotiating prisoner deals. Unlike with rogue groups, Washington has established diplomatic channels with foreign governments to facilitate deal making over detainees.

Publicly, such swaps look uncomfortably like concessions to hostage-takers. The US in September released an Afghan drug lord serving a life sentence in a New York prison to secure the release of Navy veteran Mark Frerichs by Afghanistan’s Taliban government. In other swaps this year, the US released two relatives of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro convicted of drug trafficking, as well as a Russian cocaine smuggler.

Russia, which had convicted Ms Griner of possessing a cannabis derivative, on Thursday allowed her to return home in exchange for an order by President Biden to commute a 25-year prison sentence being served by convicted Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout. The prisoner exchange took place at an air base in the United Arab Emirates.

Prisoner swaps of the past were more often associated with the exchange of spies. The US and Soviet Union traded operatives during even the worst of the Cold War. American law-enforcement officials long resisted the release of foreign nationals convicted or accused of crimes in the US.

The deal to win Ms Griner’s release sparked new worries that more Americans could be taken into custody by antagonistic governments seeking something from the US. The growing practice of what the US has called hostage diplomacy — by China, Russia, Iran, Venezuela and North Korea — prompted Mr Biden this summer to declare it a national emergency.

Since the president has sole pardoning authority, the decision about a prisoner exchange is ultimately a political one. Robert O’Brien, who served as President Trump’s hostage envoy and later national security adviser, said his view of prisoner swaps gradually changed.

“When I started, I didn’t want to do prisoner exchanges. I viewed it as a concession,” he said. By example, he cited a 2011 deal in which the Palestinian militant group Hamas freed an Israeli soldier held captive for five years in exchange for more than 1000 Palestinian prisoners. The deal came to be broadly viewed as lopsided and encouraging more abductions.

When Mr O’Brien tried to negotiate the release of Americans in Iran — including Princeton academic Xiyue Wang and Siamak Namazi and his father Baquer Namazi — Iranian officials relayed through a third country that it would cost hundreds of millions of dollars per hostage, he said.

Mr O’Brien said he came to see prisoner swaps as a useful tool under the right circumstances and involving nonviolent offenders. “I had a broad mandate from the president to bring people home,” he said, adding: “As hostage envoy, I would explore the best deal I could.”

Mr Wang came home in 2019, and the US freed Massoud Soleimani, an Iranian professor held in the US on charges of violating sanctions. Mr Wang wrote after his return that his Iranian prison interrogator told him he was to be used as one side of an exchange for US-held Iranian prisoners and the release of frozen Iranian assets. In October, Iran granted Siamak Namazi a short prison furlough and allowed his ailing father to depart the country.

Iran has previously denied wrongfully detaining Americans or using American prisoners as bargaining chips.

After the Griner-Bout trade, Debra Tice, whose son Austin, a freelance journalist and former Marine officer, has been detained in Syria since 2012, criticised the US government for telling her it couldn’t negotiate with the Assad regime given its brutality, but was willing to negotiate with Russian President Vladimir Putin. “We’ve heard for 10 years that we can’t make any concessions,” she said. “Then they publicly announced the concessions that could be made.”

In October, the biggest US prisoner swap in recent years took place on an airport tarmac on the tiny Caribbean island of St. Vincent.

After five years of detention in Venezuela and with his wrists still raw from handcuffs, permanent US resident José Pereira, a former senior executive at Citgo Petroleum Corp., led a single-file line of six other people to an American jet. Most had been jailed on corruption charges that US officials said were specious.

The released prisoners crossed paths with two nephews of the wife of Venezuela’s president headed in the other direction, toward the plane the Americans had just left. The nephews had been convicted of US drug-trafficking charges in 2016. “I wanted to say hello, but didn’t say anything,” Mr Pereira said of the tarmac exchange.

A senior Biden administration official described that swap and the one Thursday as tough, painful decisions by the president. Administration officials say such deal making is rare and not a new norm.

Florida Republican Sen. Marco Rubio expressed concerns about both swaps. He said the Venezuela deal would encourage hostile governments to capture more Americans. On Thursday, he criticised the Griner exchange.

“Putin and others have seen how detaining high-profile Americans on relatively minor charges can both distract American officials and cause them to release truly bad individuals who belong behind bars,” Mr Rubio said in a statement.

Cash payment

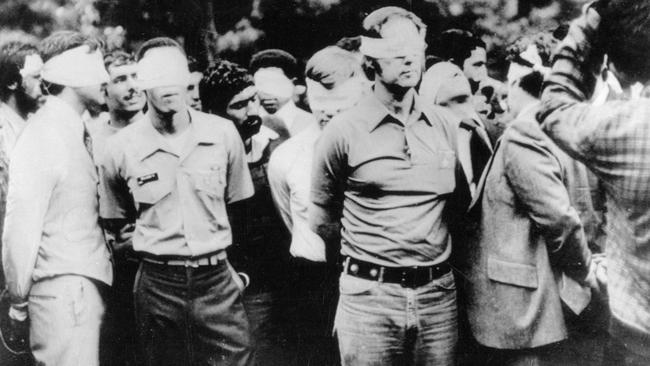

Images of detained Americans make US leaders appear helpless, and efforts to free them can backfire. President Jimmy Carter’s policy of resisting retaliation after the 1979 capture of 52 Americans in Tehran was seen not only as lengthening their ordeal but contributing to his loss in the 1980 election.

In 2014, President Barack Obama dispatched US Special Operations forces to rescue Americans held by Islamic State militants in Syria. The mission failed, and hostages, including American journalist James Foley, were killed.

Mr Obama ordered a review, and in 2015 he created a presidential envoy for hostage affairs. In January 2016, he approved the release of seven Iranians in exchange for four Americans detained in Iran. On the same day, the US released a $400 million cash payment to Iran, part of the Iranian funds frozen by Washington since the 1970s. Mr Trump, then a presidential candidate, called it a ransom payment.

As president, Mr Trump faced his own decisions over prisoners, including Otto Warmbier. The student spent more than a year captive in North Korea before his death at age 22 in 2017. Mr Trump authorised special-forces rescue missions in Yemen and Nigeria, and he, too, approved prisoner swaps.

In 2020, Congress codified in US law the term “wrongfully detained,” defining it to include citizens held specifically because of their US nationality. Human-rights groups say more than 50 Americans are currently being wrongfully detained, according to the criteria in the law.

Government captives

Joint lobbying by the families of detainees, boosted by media coverage of Ms Griner’s detention, has helped build political support for prisoner swaps.

Texans Joey Reed and Paul Reed pressured Biden administration officials and Republican lawmakers to help free their son, Trevor Reed. He was convicted of assaulting two police officers while intoxicated and sentenced to a Russian labour camp. US officials called his 2020 court trial a sham.

In April, Mr Reed was released in exchange for a Russian pilot serving a 20-year prison sentence in the US for conspiring to import $100 million worth of cocaine. Texas Sen. John Cornyn, a Republican, applauded Mr Biden and State Department officials for their behind-the-scenes work.

On Thursday, lawmakers in both parties celebrated Ms Griner’s release, though some quickly shifted focus to Paul Whelan, an American whom US officials had also hoped to free from Russia.

In a tweet, Sen. Lindsey Graham, a Republican from South Carolina, called it “a bitter pill to swallow that Mr Whelan remains in custody while we release the ’Merchant of Death’ Viktor Bout back to Russia.”

A decline in the number of Americans taken hostage abroad, including aid workers and journalists, has been offset by longer ordeals and rising cases of wrongful detention by foreign governments, according to the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation in Portsmouth, N.H.

The hostage-advocacy group, named for the journalist killed in Syria, counts an average of seven Americans held hostage each year in the past decade compared with an annual average of 34 people considered wrongfully detained by governments — nearly seven times the figure of the previous decade.

In China, dozens of US citizens are blocked from leaving the country, many over business disputes that don’t involve charges of wrongdoing. A spokesman for Beijing’s embassy in Washington said China welcomes visitors, but laws govern treatment of those accused of crimes.

Three years of efforts by top officials in the US, China and Canada produced a high-profile prisoner exchange last fall. Canada freed Meng Wanzhou, a Chinese executive of Huawei Technologies Co., after the US agreed to resolve bank-fraud charges against her.

In return, China released Canadians Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig from prison, in addition to siblings Victor Liu and Cynthia Liu of the US, who had been prevented from leaving China for about three years.

“We want the public perception to be, ‘We’ll do whatever it takes to get these people home,’ ” said Liz Frank, executive director at Washington-based non-profit Hostage US, which supports detainees and their families.

The Wall Street Journal