US Federal Reserve looks to RBA on rate strategy

Australia’s central bank is providing clues as the US Fed mulls a new policy tool to help hold interest rates low amid the downturn.

With the Fed considering a new monetary policy tool to help hold interest rates low amid the severe downturn, clues to the tactic’s effectiveness can be found in one advanced economy far away.

The Fed is eyeing Australia’s experience with so-called yield caps, in which a central bank buys enough government securities to prevent their yields from rising above a certain level or to pin yields at specific levels. This helps to hold down private-sector interest rates, which are influenced by government debt yields.

While it is too soon for a final verdict, the approach appears to be working well so far, though not without some potential costs and risks.

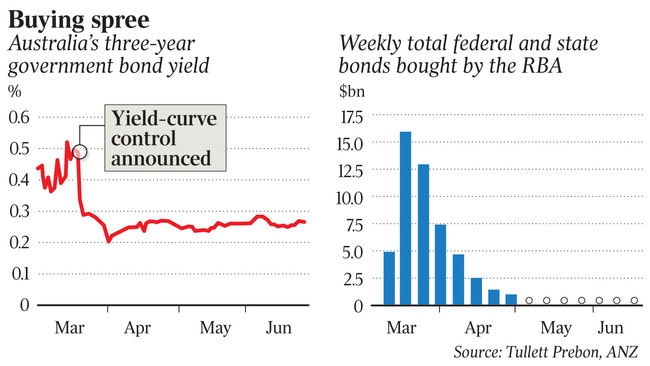

Since March, the Reserve Bank of Australia has set a target of 0.25 per cent for the yield on the government’s three-year bond. The yield declined to around that level within days of launching the policy and has stabilised in a tight range near that point.

Economists say there is a lot to like about Australia’s experience. To start, the RBA has anchored the three-year yield without having to expand its balance sheet massively. The central bank quickly bought $US35 billion in bonds to cement the policy in place, but has spent the past month on the sidelines.

The yield cap, importantly, also helps reinforce the RBA’s outlook for rates and the economy. RBA Governor Philip Lowe has said the central bank won’t raise its policy rate from 0.25 per cent until it makes progress toward full employment and it is confident inflation will remain within its 2 per cent -to 3 per cent target band. Together, this verbal commitment and the yield cap should prevent investors from anticipating central bank rate increases too soon and pushing up interest rates set by markets.

The introduction of the yield cap has proven “simple to implement and communicate, and potentially efficient from a balance sheet perspective, “ wrote Andrew Boak and Daan Struyven of Goldman Sachs & Co.

Another benefit of the RBA policy is that it directly helps lower the cost of funding mortgages.

“The RBA gets a large bang for the buck, so to speak,” said Shane Oliver, chief economist at AMP Capital, based in Sydney. “Yield-curve control may be a way for the Fed to achieve the same in terms of keeping bond yields low, and hence the cost of funding down in the US, but at the same time be buying less bonds than is currently the case.”

The Goldman economists note that while yields on three-year government securities fell in Australia, the US and Canada in March, they have held a bit lower in Australia, which suggests the policy is providing some stimulus.

But questions about the strategy remain. To start, it isn’t clear whether capping yields on short-term securities provides much stimulus if interest rates are already near zero amid a deep downturn.

Australia’s economy appears headed for its first recession in 29 years due to the coronavirus pandemic. A cumulative 835,000 jobs were lost in April and May -- equivalent to 7 per cent of the workforce -- and the inflation outlook remains weak.

“It’s not hard to get the market to believe rates are going nowhere for a long time,” said Sally Auld, a former chief economist for Australia at JPMorgan Chase.

Yield caps may not deliver as much stimulus as buying large quantities of long-term bonds to push their yields down, as the Fed did after the 2008 financial crisis to spur household and business borrowing and spending.

Yield caps tend not to be as forceful in driving bond investors out of the market and into other, riskier assets, said AMP’s Mr Oliver. That is because if the central bank doesn’t have to buy more bonds, as in Australia currently, it isn’t displacing purchases by private investors and thus prompting them to buy other assets.

One risk is that the RBA’s yield cap might be contributing to the Australian dollar’s resurgence, something that could stall the economic recovery in a nation that relies heavily on exports, said David Plank, Australia and New Zealand Banking Group’s head of Australian economics. The Aussie dollar fell to a 17-year low near US55 cents as COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, sent shockwaves through the global economy in March, but it has since recovered close to US70 cents.

The RBA’s initial success with yield caps is being actively watched at the US central bank. For the Fed, yield caps could be used to reinforce a verbal commitment to hold short-term rates very low for a set amount of time or until specific economic conditions are achieved.

Su-Lin Ong, head of market research at RBC Capital Markets, said there are limits to what the Fed might learn from Australia. US fixed-rate mortgages are funded at longer maturities in the bond market. Australia’s are funded mostly at the short end, thus benefiting from the RBA’s yield cap.

For the Fed to deliver similar economic benefits using yield caps, “longer-dated yields would have to be the target point for U.S. yield curve control, which is more difficult,” she said.

One risk for Fed officials if they try capping yields is that the market could doubt their commitment, with unwelcome consequences.

“As is the case with currency pegs, if markets do not find the target credible, achieving the rate target might require elevated purchases,” said Goldman Sachs’s Mr Boak.

The RBA’s yield-cap policy has been effective so far, partly because officials quickly made its target credible by aggressively purchasing assets early on, he said.

The Wall Street Journal

Q&A: Rebuilding Australia’s economy

Join Adam Creighton in conversation with Treasurer Josh Frydenberg in an exclusive subscriber-only online event on Tuesday July 7 at 7.30pm

Register now at theaustralianplus.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout