Uprooted: how the first enforced exodus of illegals played out

Victor Ochoa, then seven, was sent ‘home’ in President Eisenhower’s forced mass deportation in 1955. He reflects on Trump’s plan for another.

Victor Ochoa was seven when a stranger in a wide-brimmed hat came to his house and told his parents they had three days to leave the United States.

The man, brandishing a pistol beneath his trench coat, warned that federal immigration authorities would be back to make sure the family had gone. That night, Ochoa said, his mother’s wails echoed through the house while his parents made plans to leave Los Angeles and return to Mexico.

Almost 70 years later, Ochoa, who was born in the US, vividly recalled the details of that day in 1955 and the tough times that followed. His parents had arrived illegally a decade earlier and worked in factories, drove trucks and cleaned houses. They raised Ochoa and his sister to speak only English.

Days after the stranger’s visit, the family fled to the Mexican border city of Tijuana. Over the next seven years, Ochoa struggled with a new country and new language. He was bullied and called “gringo”, he said. Local children made fun of his broken Spanish, and the tap water made him sick for months. At 14, he returned to the US, settling in San Diego.

In the months before Ochoa’s family was deported, hundreds of thousands of Mexicans, as well as US citizens of Mexican descent, many of them children, were swept up in Operation Wetback, one of the largest mass deportations in American history.

It was named after an ethnic slur common at the time and was overseen by then president Dwight Eisenhower.

Former president Donald Trump has cited the operation as a model for a more sweeping deportation campaign he said he would conduct if he wins in November. He has praised Eisenhower’s proficiency in removing migrants and ferrying them deep into Mexico, far from the border.

Trump insists an alleged influx of criminals from abroad has “destroyed the fabric of our country”. At a rally in Wisconsin last week, he warned that the operation might lead to violent clashes with armed migrant gangs. “Getting them out will be a bloody story,” he said.

During the Eisenhower operation, federal immigration authorities co-ordinated raids across the borderlands and in cities from LA to Chicago. Many migrants didn’t get time to pack their belongings before being loaded into buses, aeroplanes, trains and cargo ships. Some reportedly died of dehydration after being dropped off at remote locations.

The Eisenhower administration claimed authorities uprooted more than a million people, though later estimates put the figure closer to half that.

The legal and logistical hurdles of deporting the estimated 11 million people now believed to be living illegally in America makes Trump’s promise far more difficult. During the Eisenhower administration, people living illegally in the US were mostly from Mexico, a country happy to take them back. Most lived in segregated neighbourhoods along the border or in major cities.

Recently, illegal immigrants have come from around the globe, including countries that won’t take them back. Most are clustered in blue-leaning cities and states that have laws blocking co-operation with immigration authorities. And, unlike in the Eisenhower era, they can’t be deported without a hearing in immigration court. Yet the social and political parallels between then and now are striking.

In the early 1940s, millions of Mexicans arrived to work on farms and railroads in a government program to fill jobs during World War II. Many stayed after the war. When American troops returned home, public sentiment turned against the migrants.

In 1951, the US government issued a report blaming immigrants in the country illegally for many of the nation’s economic woes.

Citing little evidence, the report accused Mexican labourers of stealing jobs from Americans and bringing death and disease. It described illegal immigration as “an invasion”.

“The greatest invasion in history is taking place right here in our country,” Trump said during his July speech at the Republican National Convention.

Politicians and newspapers during the Eisenhower era warned of communist subversives slipping across the border. Trump has alleged without evidence that droves of prisoners, terrorists and mental patients have been crossing the border and polls show most Americans view illegal immigration as one of the nation’s biggest problems.

In 1955, there was a public campaign to widely trumpet the government’s plan. The goal, according to historians, was a public relations blitz to pressure immigrants in the country illegally to flee rather than risk their families being captured in surprise raids. Twice as many immigrants might have voluntarily left than were deported, some historians said.

Trump and his allies, many of whom served in top immigration policy roles when he was president, have discussed replicating Eisenhower’s tactics, according to people familiar with the matter.

Like Trump, President Joe Biden has taken numerous executive actions to discourage new migrants from crossing the southern border. But the two parties disagree more sharply over how to treat immigrants who have put down roots over the years. Biden has taken steps to give these people work permits and, in narrow cases, a path to citizenship. Trump wants them deported.

The former president has said he would deputise local police and the National Guard to carry out mass arrests and hold migrants at converted military bases while they await deportation. Trump has also floated the idea of bypassing normal rules and invoking the Alien Enemies Act – a 1798 law intended for wartime – to deport known or suspected immigrant gang members and drug dealers without a court order.

Former Trump advisers are drawing plans to hasten court decisions in the backlog of immigration cases making it easier to remove millions.

Trump made similar promises for mass deportation in his 2016 campaign. Yet during his administration he deported about 1.2 million people, not an unusually high number for a four-year stretch. Fewer than 300,000 of them lived in the US. The rest were caught crossing the border.

Trump’s allies and critics alike believe he would be more adept at expanding deportations during a second term, despite the scale and potential consequences for many US citizens.

It is estimated about 4.7 million American children have at least one parent living in the US illegally. If those parents are deported, they would have to decide whether to take those children or leave them behind to be raised by relatives or friends.

Immigrant spouses of US citizens also risk deportation, another echo of the Eisenhower operation. In the spring of 1954, Aurora Sandoval was home with her six children in southern Texas when authorities knocked on her door. They asked for proof that she had permission to live in the US, she recalled. She was married to an American but hadn’t filed the paperwork needed for permanent residency.

The officers took her into custody and allowed her to bring her youngest child, who was still breastfeeding. Her eight-year-old daughter was left to watch the rest of the children until their father returned home from work.

Sandoval’s husband was a farmhand who worked alongside Mexican migrants. “To people at the time, my grandfather was a Mexican – who happened to have US citizenship,” said Jack Sanchez, the couple’s grandson and an immigration lawyer in New Mexico.

Back then, Americans who didn’t have paperwork on hand proving citizenship were often arrested and deported without a chance to hire a lawyer.

Sandoval and her infant daughter were loaded on a bus that night and driven to Matamoros, Mexico, across the border from Brownsville, Texas. She contacted family members who took them in. Sandoval’s husband and her other children followed. After six months, Sandoval obtained a visa and returned.

News of the deportations spread quickly in migrant communities, said Dolores Huerta, 94, the California labour leader who co-founded the group that became the United Farm Workers. She was living in California, and recalled federal authorities demanding to search every room of the hotel her mother owned.

“I told them, ‘No, you can’t do that. You have to get a search warrant’,” she recalled. Authorities conducted raids at a cinema across the street that featured Spanish-language films. They flicked on the lights during the show, she said, and questioned people in the audience. “Some of these tactics really violated people’s civil rights.”

Historians say most Americans at the time supported the mass deportation. “It was really public opinion that pushed the Eisenhower administration,” said Natalia Molina, a University of Southern California history professor who has published research on the Eisenhower operation.

But the indiscriminate nature of the deportations, especially the mistreatment of American citizens, turned formerly supportive interest groups into opponents.

In a congressional hearing at the time, Joseph Swing, a former army general who oversaw the operation as commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalisation Service, said “in such a large-scale operation, individual instances of such an unfortunate nature will occur”.

In Los Angeles, migrant communities were on edge during Eisenhower’s deportation campaign. Ochoa recalled federal authorities driving through his neighbourhood in unmarked cars. They visited his school several times and questioned teachers and students.

His mother, terrified the family might be targeted, instructed her children to hide their Mexican identity, Ochoa said. She told white neighbours her family was from Russia, hoping their relatively light skin colour would back up the lie, he said.

“My mum was worried all the time, and I think it made her sick,” Ochoa said. “I made a pact to myself that I wasn’t going to be a worry wart and I wasn’t going to be stressed out all the time.”

Ochoa said the years he spent living in Tijuana helped connect him with his Mexican identity. But he worried about his education and eventually persuaded his mother to let him live in the US with a family friend so he could study at an American high school.

He sometimes went more than a year without seeing his parents, who couldn’t afford to pay for him to visit. In Tijuana, he said, they earned little compared with US wages. During visits to Mexico, Ochoa said he carried his birth certificate and took care to enunciate his words when speaking with border guards.

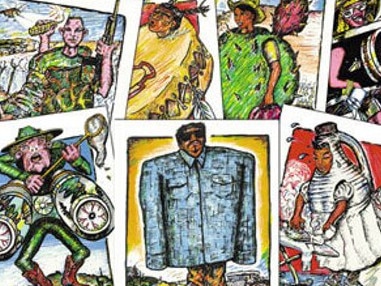

Ochoa, 76, is now a prominent San Diego muralist and activist. His artwork, depicting the plight of Mexican migrants, is sprawled across freeway underpasses at Chicano Park, a National Historic Landmark in the city’s oldest Mexican-American neighbourhood.

Ochoa lives less than a 20-minute drive from Tijuana, where he maintains his late parent’s house. Some members of his family still in Mexico aspire to live in the US. A few have discussed crossing the border illegally. “Everybody wants to survive,” he said.

Last year, at a family reunion, Ochoa learned first-hand about the divide between his relatives in Mexico and younger family members who were born in the US. When he showed his family a binder of his art advocating for migrants, some of them scoffed and said they were Trump supporters.

Trump, they told him, would do more to lower their taxes.

“I can’t believe that these are second-generation Mexicans siding with Trump,” said Ochoa, a self-described progressive. “If it’s happening with my family, I’m sure it’s happening all over.”

The Wall Street Journal.