Unrecognised in their own time

If these geniuses failed to achieve success while they were alive, there should be hope for every struggling artist.

With her men’s coats and floppy hats, her hair and cheeks shiny with Vaseline, Vivian Maier was a conspicuous figure on Chicago’s North Shore before she died in 2009 at the age of 83.

Locals gave her an array of nicknames – Bird Lady, Army Boots, Wicked Witch – never realising that the old woman who haunted the same park bench nearly every day would one day be deemed an artistic genius.

To the great shock of everyone who once knew her, including the many families who employed her as a nanny, Maier left behind an archive of over 140,000 photographs, many of which transformed the ordinary detritus of life into something extraordinary.

Since the first major exhibition of her work a decade ago, selections of Maier’s oeuvre have travelled the world, including to Australia.

Her sensitive, serendipitous snapshots, mostly of strangers in the cities where she lived – Chicago, Los Angeles, New York – have earned her a place in the pantheon of street photographers, alongside Diane Arbus, Robert Frank and Garry Winogrand.

As Ann Marks writes in a riveting new biography, it is remarkable that any of these photographs ever managed to come to light. Because Maier failed to meet her storage-locker payments, her abandoned negatives and unprinted rolls of film went to auction in 2007, where a 26-year-old history buff named John Maloof bought a box of them on a lark for around $400. Impressed by the work, he swiftly amassed whatever of hers he could find and then tried to drum up public notice, first through a blog, then with an exhibition at the Chicago Cultural Center in 2011.

“The reaction was explosive,” Marks writes. More people attended the show than any other in the centre’s history.

Maier’s story may be singular, but it follows a familiar arc: the overlooked or misunderstood genius whose true gifts earn acclaim only after death.

She now joins the ranks of some of our most beloved artists – Emily Dickinson, Peter Hujar, Franz Kafka, John Keats, Amadeo Modigliani, John Kennedy Toole, Jonathan Larson – whose fame has been enhanced by having lived fameless lives. In the world of art, we appreciate quality, but we are suckers for stories of runaway posthumous success. They are the ultimate underdog tales, at once tragic and triumphant.

Part of the appeal of artists who would never know their own success is that their lives were often, like ours – beset with frustration, rejection and money woes.

Edgar Allan Poe, for example, earned some attention as a critic and made a splash with The Raven, but he barely scraped by before dying in mysterious circumstances at the age of 40 in 1849. Poe’s posthumous influence has been staggering. “Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?” observed Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes.

But while Poe was alive, he was sometimes reduced to begging on the street and subsisting on molasses and bread.

The humbling and often humiliating trials of now lionised artists reinforce our sense, or at least our hope, that while life is often unfair, truth and beauty will win out in the end.

The creative life is usually a demoralising one, so stories of great artists who lived without affirmation and died unknown can be consoling. What is more encouraging than the thought that our own stories aren’t over even when we die? Art has the potential to be immortal, but posthumous fame offers resurrection.

Perhaps this explains the perverse thrill that might come from learning that Herman Melville’s Moby Dick was a flop when it was first published in 1851. “So much trash,” carped one critic. Another called it “outrageously bombastic”.

Punished for his ambition and saddled with debt, Melville was in his late 40s when he took a job as a New York City customs inspector, which he held for nearly two decades. When he died in 1891 at 72, many of his peers thought that he was already dead.

If critics were wrong about Melville, how can they be trusted? If Poe failed to live by his pen, how can anyone else? The sting of defeat feels a touch less painful when we know we are in such good company. What is more invigorating than learning that despite the setbacks, these and other artists kept writing and painting and rolling boulders up hills?

When famous artists are spurned in their lifetime, we often praise them for being ahead of their time. By this calculus, success can seem almost damning, a consequence of artistic compromises. “I’m not interested in celebrity,” Jean Genet, the French novelist and playwright, reportedly once said. “I’m interested in glory, and glory is posthumous.”

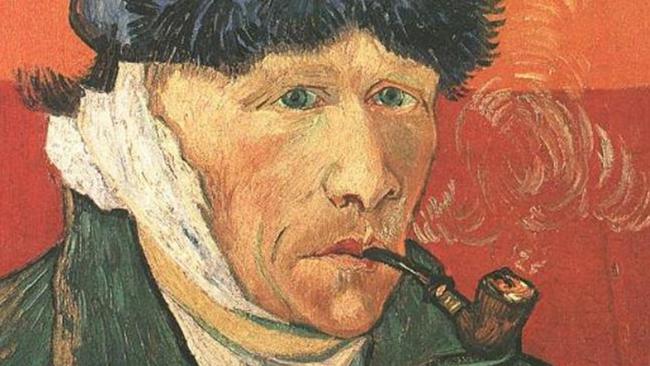

Vincent van Gogh’s tragic story – his pain and ambition, his self-mortification, and his death at 37, presumably by his own hand – has always been part of his mystique. His life may have been bleak, but his tenacity and originality in the face of rejection (he sold just one painting in his lifetime) are the stuff of artistic legend.

When we recognise brilliance posthumously, we preserve the purity of art made urgently, without the taint of commercial success. Sylvia Plath, for example, is forever fixed in the creative ferment of her dark final days in a dank London flat. Furious over her husband’s faithlessness, unable to sleep or eat, she wrote at dawn, before her children were awake, and poured her feverish self into the glistening, venomous poems that would outlive her.

When Plath killed herself at 30, in 1963, local reports announced that she was the “wife of one of Britain’s best-known modern poets, Ted Hughes”, but her fame soon eclipsed his.

Feminists have embraced her as a kind of martyr, liberated on the page in a way that she could never be in life. That Plath grimly ensured she would never witness the reception of her finest poems can make them seem more vital.

In this way, posthumous fame promises to correct the injustices of history. Spinsters who published anonymously in their lifetime, if at all, such as Jane Austen and Emily Dickinson, are now hailed as trailblazers.

Artists shoved into the shadows by the prejudices of their time, such as Phyllis Wheatley, a former American slave who found fame for her poetry overseas but died as a poor maid in Boston in 1784, are finally getting their due.

As Wheatley once wrote of her own “cruel fate”: “Such, such my case. And can I then but pray/Others may never feel tyrannic sway?”

Maier was yet another spinster, dismissed in her time, whose fame feels vindicating.

Marks finds evidence that Maier had hoped to become a professional photographer, but as an amateur without credentials or connections she never made much headway. Maier therefore worked solely for herself – discreetly, defiantly – and captured the beautiful mess of life with the clarity of an outsider.

When we learn that genius was once disguised as a nanny – or a customs inspector, or a beggar – nothing quite looks the same.

Who else at the local playground is quietly generating breathtaking works of art?

Which bank teller or waiter or insurance salesman is sitting on a trove of remarkable paintings or poems or novels?

Lurking beneath the plain surface of life roils a torrent of creative potential, unnoticed and quite possibly glorious.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout