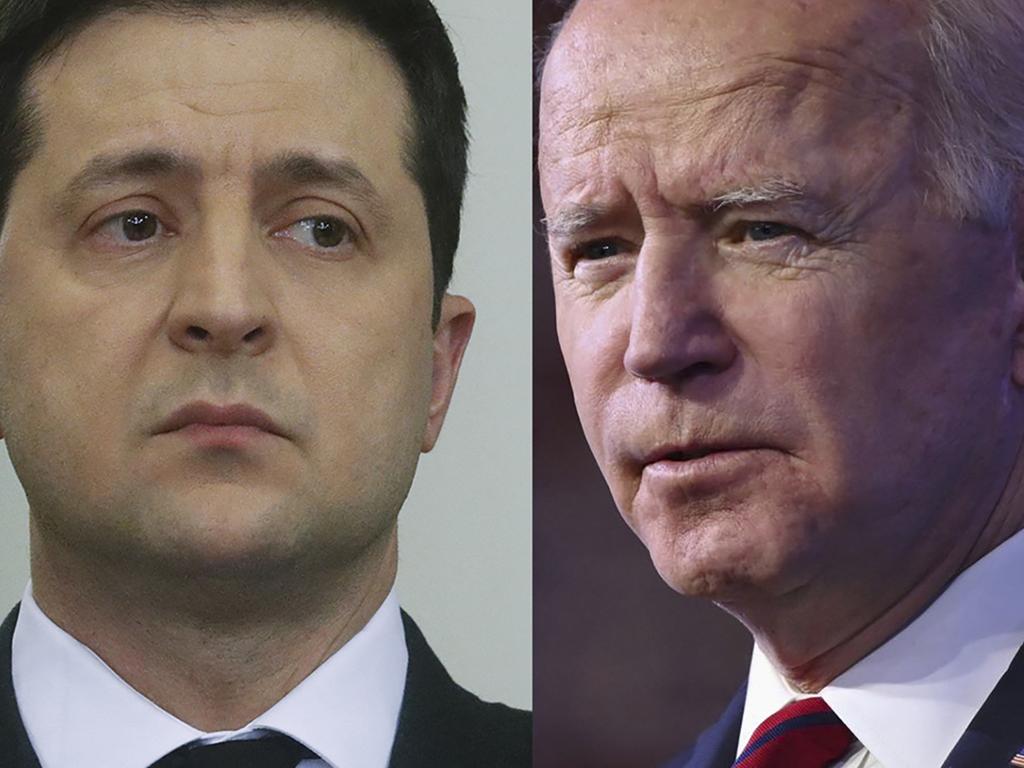

Ukraine brings back agonising realpolitik decisions

There also is this echo: The U.S. now has to decide whether to return to the days of realpolitik, when it held its nose to foster good relations with unsavoury regimes to better confront a larger danger emanating from Russia.

Increasingly, the Biden administration faces that choice when it comes to relations with Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Iran and some of the more autocratic governments in Europe. And now, as in the Cold War, overhanging it all is the mega question of whether the U.S. can foster better relations with China to offset a Russian menace, despite misgivings about Beijing’s policies.

As it becomes clear that Mr. Putin’s ruthless onslaught in Ukraine and his possible ambitions to go even further will produce long-term shifts in global relationships, those questions are going to come increasingly to the fore. The world faces a period of choosing — with Mr. Putin or against him? — as well as a need to realign existing patterns of energy, food and technology production.

In such a shifting landscape, the U.S. requires friends, both old and new. And the price it is willing to pay to secure and retain those friendships is up for reconsideration.

That’s where realpolitik comes into play. Realpolitik is the practice of engaging in international relations based on practical needs rather than moral or ideological considerations. It implies a certain cold-blooded willingness to look the other way when it comes to a regime’s fealty to democratic values or even respect for human rights, or to at least play down those concerns, to focus on a larger threat.

The need to confront what appeared to be an existential challenge from a hostile, nuclear-armed, Soviet, Communist behemoth justified such decisions half a century ago. That need led the U.S. to foster good relations with military dictators in Latin America, undemocratic monarchies in the Middle East, strongman leaders in the Philippines and military-dominated governments in Pakistan. Early on in the Cold War, the need to confront the Soviet threat prompted the U.S. to look past the World War II transgressions of Japan and Germany to create a more favorable balance of global power.

But that didn’t make all those decisions easy or noncontroversial. Debates raged over whether the U.S. was making unwise or even immoral choices in pursuit of anti-Soviet friendships, and whether it was sowing the seeds for long-term unrest and alienation from swaths of world citizens by befriending leaders who ruthlessly suppressed internal debate and dissent. The debate culminated in the late 1970s, when the administration of President Jimmy Carter decided support for human rights deserved a place as prominent as pursuit of geopolitical advantage in America’s foreign-policy calculations.

Fast forward to today and a new set of such agonising choices faces the Biden administration. The U.S. needs more oil on the international market to ease the economic shock that will result if more Russian oil is blocked. Does that justify swallowing misgivings about the totalitarian nature of Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro, or the assassination of a journalist by the rulers of Saudi Arabia?

Does that same need for more oil on the world market, as well as a desire to clear the decks of other international distractions, compel the U.S. to move more rapidly toward a nuclear deal with Iran’s hostile theocratic regime? And does the need for a unified Europe mean looking past the autocratic tendencies of Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban?

Already there are signs that the new world order that began taking shape when Russian tanks moved into Ukraine has altered American calculations. U.S. officials made a surprise visit to Caracas to renew talks about lifting sanctions on Venezuela’s oil industry, after which Mr. Maduro released two detained Americans and said his government would resume negotiations with his internal opposition.

The Journal is reporting that the Biden administration has just met longstanding Saudi requests by transferring a significant number of Patriot antimissile interceptors to help the kingdom in its fight with Houthi rebels in neighboring Yemen. Meantime, the U.S. is weighing whether to make a controversial concession to Iran by removing the country’s Revolutionary Guards from its list of terrorism organisations in order to close a new nuclear deal.

The largest question of all is whether the U.S. is prepared to hedge some of its concerns about Chinese behavior to prevent the emergence of a new Moscow-Beijing axis. Is it willing to mute its complaints about China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims or some of China’s trade practices? Such questions were tough ones during the Cold War — and are no easier or simpler now.

The Wall Street Journal

Thanks to Vladimir Putin’s assault on Ukraine, Cold War echoes can be heard all around: escalating tensions with Moscow, a newly unified Western military alliance, rising defense spending, even a whiff of fear over potential nuclear conflict.