This was supposed to be the antidote for TikTok brain. It’s just as bad

YouTube Shorts adds ‘short bursts of thrills’ to kids’ digital diets, making it harder to pull away.

TikTok’s surging popularity has led to copycats from YouTube and others, spreading the rapid-fire video format across teens’ smartphones. It also has fuelled the attention-robbing problems that come with such clips.

YouTube used to be the place where teens and preteens watched lengthy toy unboxings and video game tutorials. Many parents who banned their kids from watching TikTok considered YouTube to be a safer alternative.

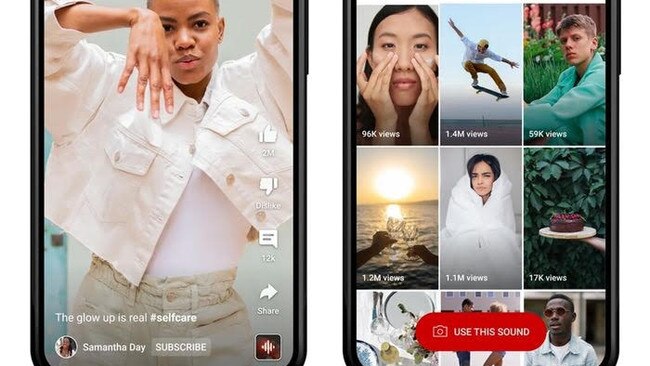

But since the debut of YouTube Shorts two years ago, YouTube looks more like TikTok – something new research suggests is a problem. Viewing endless 15-second TikToks hurts kids’ attention span and makes it harder for them to participate in activities that don’t offer instant gratification, an effect I dubbed “TikTok brain”.

Longer videos are still on YouTube, but it’s the short ones that have recently captured kids’ attention. YouTube Shorts have a maximum length of 60 seconds. They are watched by more than 2 billion logged-in users every month, up from 1.5 billion a year ago, parent company Alphabet said last month.

Children who used to be able to regulate their YouTube-watching now have trouble pulling away from the short videos, some parents say. A new study by the Guizhou University of Finance and Economics in China and Western Michigan University found short-form videos such as those on YouTube and TikTok engage people through “short bursts of thrills”, which can make it easier to develop addictive behaviour.

YouTube spokeswoman Ivy Choi said research into how short-form content impacts young people is still in its early days and the company is closely monitoring it. She added that reminders to take breaks and to go to bed are on by default for users ages 13 to 17.

“At YouTube, protecting the safety and wellbeing of young people and their families is core to our work, including for YouTube Shorts,” Choi said. “We continue to refine the Shorts experience to better meet the needs of young people and their families, including by partnering with third-party experts to inform our work.”

Robert Verderese says his 14-year-old son has become so absorbed in YouTube Shorts he can’t seem to hear his dad tell him to put down his phone, even though he doesn’t wear headphones.

“I’ve said, ‘I’ll give you $1000 if you look up at me right now’, and three seconds later he looks up and says, ‘What?’,” Verderese says.

His son used to watch YouTube tutorials while playing video games so he could learn how to improve as a player. In the past year, the teen has mostly been watching Shorts purely for entertainment.

Verderese, an equities trader in New York, has become so frustrated with the quick videos that he emailed Alphabet to see if there’s a way to disable Shorts (there’s not) or to set a time limit for the short videos (also not possible).

The study from the Chinese and Michigan universities, published this month in Computers in Human Behavior, a scholarly journal that examines technology from a psychological perspective, suggests Verderese’s concerns about short videos aren’t an over-reaction.

Researchers surveyed college students in China and the US to discover why they excessively watch short-form videos: for entertainment, to gain new knowledge and to build and maintain their social identities. The researchers recommended students curb such viewing with more offline activities. They said other online activities, such as video games, require longer durations and continuous engagement to drive behavioural addiction.

Previous studies found that watching fast-paced videos interferes with children’s ability to perform tasks correctly and decreases their ability to control their impulses.

“When kids spend a lot of time watching short videos, they expect to continually be stimulated by fast changes in content,” says Gloria Mark, a professor of informatics at University of California, Irvine.

Regular viewing of fast-paced videos can make everything else seem boring and cause problems with focusing on slow-paced activities such as schoolwork and reading, says Mark, who wrote a book about attention spans, published earlier this year.

And children spend a lot of time on YouTube. It’s the social media app most used by American teens, with 19 per cent saying they watch YouTube almost constantly, according to a Pew Research Centre study published in April.

Scott Migliori, a money manager in California, says he can’t prove YouTube Shorts is the reason his 14-year-old son has lost interest in reading over the past six months, but he believes it can’t be helping.

Migliori used to worry about the amount of time his son spent playing video games. “Now I’m like, ‘Please play ‘Fortnite’,’’ he says, explaining that the game is longer, social and involves teamwork, as opposed to solo Shorts watching.

His son, who used to enjoy watching basketball games, now only views highlights via the “key plays” feature on YouTube TV. “This generation is being hardwired for instant gratification, and it’s starting to feel like a losing battle,” Migliori says.

Quick tips

Set goals: “Attention is goal-directed. If we don’t have a clear goal, it’s easy to get absorbed in videos,” Mark says. “Help your kids create goals, like playing with other kids in real life or spending time outside.”

Use tech settings: Parents of kids under 13 can create supervised YouTube accounts, in which they can choose age-appropriate content settings.

Although there’s no way to set limits on Shorts specifically, parents can set time limits on YouTube overall through Google Family Link.

Parents with Apple devices can set time limits for YouTube on their children’s devices or through Apple Family Sharing, but a bug can cause the Screen Time settings to reset.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout