The verdict on Trump’s economic stewardship, before Covid and after

The President has presided over two economies: before Covid and after. The many achievements of his first have been wiped out.

Donald Trump has presided over two economies during his time in office.

In the first, which lasted until March, the economy reached historic milestones for jobs, income and stock prices. While it’s debatable whether it was the best U.S. economy ever, as the president has said, it was without question good and getting better for millions of Americans.

The second part, which arrived with Covid-19, was historically bad. It sent unemployment to depths unseen in post-Depression records before reversing itself quickly but only partially, leaving the U.S. with an outlook that’s especially hard to forecast.

The two economies will be factors driving the choices voters make in November. The reality for Mr. Trump: Many achievements of his first economy have been wiped out by the second.

The president’s economic record never fully fit the black and white story told by either his ardent fans or his furious foes. His detractors said his tax policies catered to the rich, yet poverty and inequality fell. Minorities were big beneficiaries during his first three years, though they have also been big casualties in the past seven months.

His backers note that the growth rate accelerated as Mr. Trump said it would, but it didn’t speed up as much or in the ways he projected. Blue-collar towns reaped some of the revival his trade policy aimed for, but that revival was far from complete when it was set back by the pandemic.

A lesson that became clear after a health crisis knocked the economy off the rails: One of the best ways to advance broad-based prosperity is to keep an expansion going. Good things tend to happen, especially to those typically left behind, in the late stages of long expansions. The one that ended in March was the longest recorded in U.S. history, an accomplishment Mr. Trump shared with his predecessor, Barack Obama.

The pandemic was a reminder that the economy’s performance is heavily subject to events outside a president’s control, regardless of ideology. A key test for presidents is thus how they handle unexpected disruptions.

Mr. Trump received higher marks on dealing with the economy than Joe Biden in a Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll after their September 29 debate and in general has outpolled his rival on this issue. In addition, a Gallup survey in September found 56% of Americans said they were better off than four years ago, higher than Ronald Reagan or Barack Obama polled the years they were re-elected. However, in the same poll, Mr. Trump received lower marks than Mr. Biden for being able to deal with the coronavirus crisis that hurt the economy.

The White House is projecting a V-shaped recovery, though signs are also emerging of a K-shaped upturn, where the fates of households and businesses diverge widely. Whatever shape the recovery ultimately takes, the U.S. pursues it amid unusually high levels of both uncertainty and government debt.

Here are five takeaways from the Trump economies that led to this point.

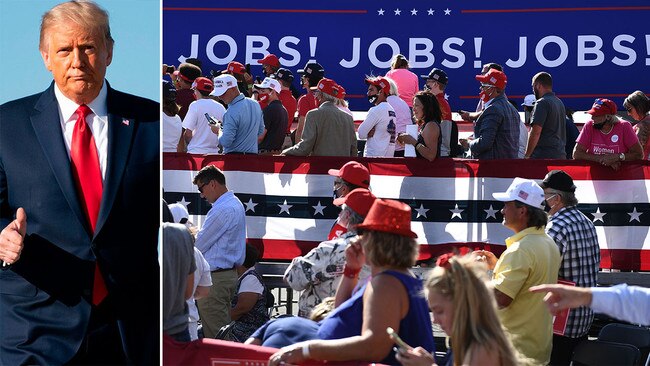

1. JOBS: Better Than Expected Until Crisis Struck

A few weeks after Mr. Trump was elected in 2016, Federal Reserve officials gathered to update their economic outlook and interest-rate plans. The consensus in the Fed’s boardroom and among many outside forecasters was that the unemployment rate, then 4.7%, would level out around 4.5% and sit there for the foreseeable future.

Instead, by the end of 2019 it had fallen to 3.5%. The pace of job growth had been projected to slow and it did, but less so than many economists expected. It averaged 2.6 million jobs a year during Mr. Obama’s second term and 2.2 million a year in Mr. Trump’s first three years.

One thing that drove the jobless rate lower was a fiscal boost in 2017 and 2018, first from Mr. Trump’s corporate and individual income-tax cuts and then from a February 2018 bill that reset spending caps Republicans had demanded in the Obama era.

“I remember thinking at the time that the last thing the economy needed was a substantial tax cut and fiscal boost,” said Janet Yellen, who led the Fed early in Mr. Trump’s term. The worry at the Fed was that the economy might overheat and spur inflation. In the event, inflation rose to the Fed’s 2% target in 2018 and then receded. Long-running trends, including globalization and the advance of technology, helped to keep it in check by restraining the cost of producing goods.

Low unemployment produced cascading benefits. Wage growth accelerated, and opportunities for low-skilled workers grew. People with disabilities or criminal records, for the first time in years, found themselves sought after for work. Firms turned to internal training programs to give workers needed skills.

“It is hard to accomplish those things until firms are really finding it tough to hire,” Ms. Yellen said.

As the jobless rate fell, Mr. Trump was a loud voice on the sidelines at the Fed, criticizing the person he had chosen to replace Ms. Yellen, Jerome Powell, for raising interest rates.

“I thought you told me he was going to be good,” Mr. Trump complained to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, as rumors swirled that the president might try to fire Mr. Powell.

The Fed reversed itself on rate increases after it saw inflation retreat. Then, when the coronavirus struck, the Fed cut rates and launched programs to flood the financial system with funds. Mr. Trump said Mr. Powell was the “most improved player” among his appointments.

The economic damage from social distancing and states’ shutdowns overwhelmed the gains from Mr. Trump’s first three years. The jobless rate hit 14.7% in April.

By September, the rate was again declining more quickly than the Fed expected, standing at 7.9% last month. Still, the jobs recovery is far from complete. Five million more people were unemployed in September than when Mr. Trump took office.

2. GROWTH: A Modest Acceleration from an Unexpected Source

The expansion that started in mid-2009, after the financial crisis, was historically slow. Mr. Trump said he would change that. His first budget in 2017 projected that the growth rate under his policies would pick up to 3% by 2020 and stay there. Mr. Trump often said it would be even higher.

The growth rate did rise, but not as expected.

During the expansion under Mr. Obama, gross domestic product grew at an average annual rate of 2.25%. It picked up to a 2.5% rate over Mr. Trump’s first three years in office, according to Commerce Department figures. Mr. Trump’s advisers said in interviews Mr. Obama had failed to deliver the boom that typically happens early in an expansion and they instead helped create one at the end.

One important driver was government spending. Federal spending grew faster during the Trump years, even before the Covid-19 crisis, than during the Obama years. Much of the increase was in defense, though nondefense spending also rose.

Excluding the effects of federal spending, GDP grew at the same rate during the Obama phase of the nearly 11-year expansion as during the Trump phase.

Federal revenue growth didn’t keep up. Mr. Trump had said in his first budget that faster growth would combine with fiscal restraint to put the government on a path to balanced its budgets and pay down federal debt. Instead, budget deficits widened late in the expansion, when deficits in the past have tended to recede.

Mr. Trump’s tax cuts and a push to scale back government regulation were meant to spur private-sector business investment and worker productivity to set U.S. growth on a faster track for the long term.

In the pre-Covid Trump economy it wasn’t clear that was happening. Productivity rose, but it didn’t approach the elevated levels achieved during the 1960s, late 1990s or early 2000s.

Business investment traveled a serpentine path. After jumping following the 2007-2009 recession and slowing later in the Obama administration, business investment rose again after Mr. Trump’s business-tax cuts of late 2017. Then it slowed again when he challenged trade rivals with tariffs. All together, the pace of business investment was slightly slower during the Trump part of the long post-2008 expansion than during the Obama part.

Now, another headwind to a long-run growth pickup is reasserting itself. Declining birth rates and retiring Baby Boomers have been restraining the expansion of the workforce.

The period of low unemployment before the pandemic provided a respite, because higher wages and more opportunities drew new workers into the economy. The pandemic reversed those gains. In the spring, the percentage of working-age people who had a job or were looking for one fell to its lowest level since the 1970s. It has made up less than half of the ground lost since then.

Growth went haywire as states shut down local economies and then reopened at different paces. Washington’s salve was an explosion of government intervention — trillions of dollars in payments to households, small businesses, states and the airline industry.

Kevin Hassett, a former Trump economic adviser, said the president reached across the aisle in a moment of crisis. “They passed a really effective stimulus bill in a House that had just impeached the president, ” he said.

Even with this support, by summer the U.S. output of goods and services was running at an annual rate — $19.5 trillion — that was $1.9 trillion below the year before. A majority of private-sector economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal this month estimated the gears of the economy wouldn’t be turning fully again until late 2021 or later.

3. Winners and losers: Low-Income Workers and Minorities Were Both A decade ago, Leroy Johnson was working an $11-an-hour customer service job for United Airlines in Hartford, Ct. Black and single, he had started college at a New York state university but didn’t finish. Over the next 10 years, Mr. Johnson enjoyed an impressive run at United.

He worked his way up through maintenance and operations jobs, becoming a manager in San Francisco, and was making nearly $100,000 a year before the virus hit. “My 401k was definitely doing pretty well,” he said.

During the first three years of the Trump presidency, median household incomes grew, inequality diminished, and the poverty rate among Black people dropped below 20% for the first time in post-World War II records. The Black unemployment rate went under 6% for the first time in records going back to 1972.

Mr. Trump and his aides cite these developments as among his biggest achievements. “We had tremendous increases in living standards,” said economic adviser Lawrence Kudlow. “Wealthy people did well, but non-wealthy people did the best. Like him or not, these are great economic achievements.” The biggest gains in income happened in 2019 as the jobless rate reached new lows.

“We saw over those three years that we could sustain an economy with much lower unemployment than had previously been thought possible,” said James Stock, a Harvard professor who studies business cycles and a former Obama economic adviser.

Some of these trends had started to click in during Mr. Obama’s second term. For example, inflation-adjusted median household incomes started moving higher in 2013 after more than a decade of stagnation. Similar milestones were reached late in the expansions of the 1960s and 1990s.

Like other United Airlines managers, Mr. Johnson, who is 33, took a 20% pay cut after the virus struck and the expansion ended. He escaped a storm of layoffs and in June got word he was being promoted to senior manager for airport operations, soon to earn more than six figures.

Many others haven’t had that good fortune. While minorities and low-skill workers tend to do best late in expansions as the jobless rate falls, they also tend to be hit first in downturns when some firms dismiss the most recently hired.

The Black unemployment rate in September was 12.1%, reversing all of the gains achieved since 2014. The jobless rate for high-school graduates with no college was 9%, reversing the gains since 2011.

4. Trade and the blue-collar job: An Unfinished Project Mr. Trump’s trade policies, most notably tariffs on imports, were aimed at helping blue-collar towns hurt by competition from China, Mexico and other low-wage countries.

Reviving that part of the American economy wasn’t going to happen overnight and didn’t.

The U.S. manufacturing sector shed eight million jobs, more than half its workers, between 1979 and 2009. Manufacturing employment began a modest ascent in 2010 and extended those gains under Mr. Trump.

The Covid-19 crisis knocked manufacturing employment back down to levels comparable to the 1940s.

The disruptive forces of technology and global trade didn’t disappear during the expansion. In the past two years, service-sector workers have passed manufacturing workers in average hourly wages for the first time on record, according to the Labor Department.

The bicycle industry shows the obstacles that lay in the way. The Trump administration imposed tariffs up to 25% on bicycles and bike parts imported from China beginning in 2018. Trek Bicycle Corp. makes custom high-end bikes costing up to $4,000 at its hometown of Waterloo, Wis. Moving its Chinese production of lower-end bikes to Wisconsin, too, didn’t make sense to Trek.

“In order to build in volume, you need a supply base around you. Nobody is making bicycle tires here, or crankshafts or derailleurs or rims,” said John Burke, Trek’s chief executive. “All of those parts come from Asia.” After Mr. Trump imposed bike tariffs on China, Trek moved some production to Cambodia.

Trade itself turned out to be a drag on the economy. U.S. export growth slowed starting in 2018 as Mr. Trump’s tariff battles ramped up. The U.S. trade deficit, reflecting an excess of imports over exports, grew to $577 billion in 2019 from $481 billion in 2016.

The gap widened further after the coronavirus struck. Exports fell as the global economy collapsed.

Also widening the gap was a boom in U.S. demand for imported electronics from China and elsewhere, needed for classrooms and home offices as the nation went into isolation. U.S. imports of computers and semiconductors in 2020 rose $6 billion through August from a year earlier, according to the Commerce Department.

5. Wanted in the White House: Crisis managers In the 1970s and 1980s, recessions tended to be driven by Fed decisions to raise interest rates to fight inflation. As inflation receded in recent decades, a different threat to expansions emerged: The unexpected shock.

In the early 1990s it was Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, which drove up oil prices and deflated business profits and household spending power. In the 2000s, it was a housing bust that crippled the banking system. This year, it was the pandemic.

Against that backdrop, Mr. Stock of Harvard said crisis-management savvy has become an important measure of economic stewardship. “Expansions don’t end of old age,” he said. “They end because something bad happens. What can one do to avoid those triggers, those really big bad events?” Mr. Trump says he responded aggressively to the coronavirus by clamping down on travel from China, getting ventilators to states and marshalling a strong financial rescue program. His opponents say he played down the severity of the virus, largely left states to fend for themselves and provided a financial rescue only with the help of Democrats.

Republicans say governors in states run by Democrats hurt the economy by keeping shutdowns in place too long. Democrats say the economy can’t get back on track until the virus is contained.

One way to measure economic performance during the health crisis is by comparison with other countries. In growth, the U.S. isn’t exceptional.

Every major economy will shrink this year except China’s, which is projected to grow 1.9%, says the International Monetary Fund. The U.S. contraction of 4.3% will be in line with that of the world as a whole, the IMF projects. It expects the U.S. to outperform some large rivals, such as Germany, Japan and Canada, but underperform others, including South Korea, Australia and Taiwan.

On government debt, the U.S. is projected to take on more than any other nation in 2020, relative to size, according to the IMF.

Federal debt has increased by $5.6 trillion on Mr. Trump’s watch. It is on course to surpass the debt added in the Obama years by the end of 2022, meaning in six years versus in eight.

Debt the U.S. has taken on in the health crisis, during Mr. Trump’s second economy, has cushioned the downturn. With interest rates very low, it is manageable for now. The risk, economists say, is that the debt level could hinder the nation’s ability to invest in the future, restraining the nation’s pursuit of faster economic growth.

WSJ

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout