The missteps in Washington and Tehran that brought Middle East to the brink

The Biden administration is trying to head off strikes that could exceed Iran’s April launch of 300 missiles and drones at Israel, the biggest test yet of its nearly four-year effort to contain the regime. Tehran, which prefers using proxies against its adversaries, is considering whether to retaliate directly again, even at the risk of a broader war.

The stakes for Washington and Tehran are significant: A major Iranian attack that provokes a further Israeli response would set back U.S. hopes for a ceasefire in Gaza and could expose Iran’s vulnerabilities, weakening its position as a regional power.

The U.S. in recent days warned Tehran directly as well as through intermediaries that a significant retaliatory attack on Israel could pose a grave risk for Iran’s government and economy.

Neither the U.S. nor Iran aimed to be in this situation, yet they have little choice now but to stumble through it and hope a full-scale conflict isn’t the end result.

Washington expects an assault on Israel as soon as this week, although the U.S. is unsure of its shape and scope.

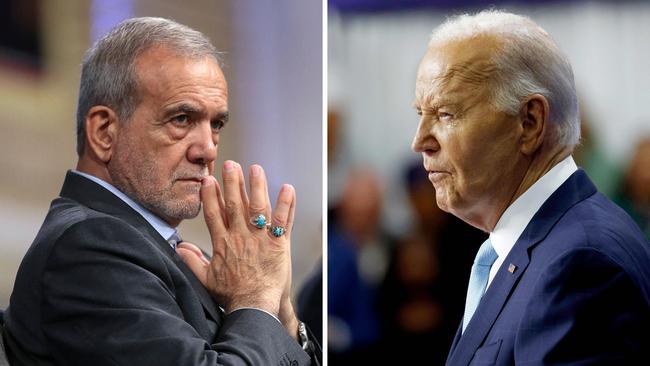

“We truly don’t know if they will do it, when they will do it, and with what force they will do it. We don’t have firm answers for all of that right now,” a senior administration official said. “But we believe an attack of some sort could very well come, potentially soon and without much notice.” An attack in Tehran that killed Hamas’s leader, which Iran blamed on Israel, sparked vows of swift revenge. It came only hours after an Israeli strike that killed a Hezbollah commander in Beirut. Iran’s new president, Masoud Pezeshkian, said it was his country’s “legal right” to retaliate.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office indicated that it is co-operating with White House efforts to de-escalate tensions, agreeing to join U.S.-organised ceasefire talks set for Thursday. But it has also threatened to respond harshly to any attack from Iran. Israel hasn’t ruled out an offensive in southern Lebanon if Hezbollah strikes.

President Biden told reporters on Tuesday that he expected Iran would refrain from strikes if the parties reached a deal. But he acknowledged “it’s getting harder” to complete a ceasefire agreement, an assessment that comes as U.S. officials travel to Qatar for another round of diplomacy.

White House spokeswoman Karine Jean-Pierre said Wednesday that the U.S. expects “these talks to move forward as planned.” In a sign of its continued intransigence, Hamas said it wouldn’t attend negotiations this week. Israel will participate, but Netanyahu has shown little willingness to get a deal done in recent months. U.S. officials concede that the door to a grand bargain is closing, prompting the Biden administration to develop a last-ditch “bridging proposal” meant to resolve the differences between Hamas and Israel over a ceasefire agreement.

Without a ceasefire, “it’s hard to see the Iranians, or Hezbollah for that matter, backing off,” said Dalia Dassa Kaye, a Middle East security expert at UCLA’s Burkle Center for International Relations.

U.S. officials and analysts say Tehran has several potential paths, all with pitfalls. Backing down would make the regime look weak. Launching a massive attack, which risks a broader fight, would invite Israeli counterstrikes Iran couldn’t stop. And replaying the April barrage would render the Islamic Republic feckless – and still raise the chances of a wider war.

Some observers suspect Iran might be trying to pry open another door: delaying until after the ceasefire talks, so if there is an agreement Tehran can claim its threats rendered regional peace.

“There is no doubt intense debate within Iran’s leadership about how to respond because none of their options look good,” said Kaye.

Biden entered office hoping to contain Iran by reviving the nuclear deal and building a fresh patchwork of regional allies to thwart its aggressions. Instead, Washington watched as Tehran edged closer to relaunching its nuclear program, backed proxies that killed three U.S. troops in Jordan and disrupted global commerce, and supported Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Islamic Republic’s biggest shift was moving its shadow war with Israel into the light. After Israel in April killed senior Iranian military officers in Syria, Iran eschewed the usual playbook – deploying proxies to level a counterpunch, giving Tehran a thin veil of deniability.

Iran alternatively opted to launch weapons at its enemy directly from its territory for the first time since the regime came to power in 1979. A combination of Israeli, U.S. and regional defences stopped the barrage from killing anyone or severely damaging military and civilian targets.

After the July killing of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh at an Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps guesthouse hours after Iran inaugurated its new president, the clock on how Tehran would respond to that attack started ticking.

“They put themselves in the position to have to do something,” said Alex Vatanka, the Middle East Institute’s Iran program director, “and this time they needed to be more impactful without creating another round of retaliations by the Israelis.” From Biden on down, the administration has repeatedly warned the regime not to escalate the current situation, using diplomatic and military levers to stave off the worst outcomes.

Beyond co-ordinating with European and Middle Eastern partners, U.S. officials have sent direct and indirect communications to let Iran know that Washington doesn’t want a wider war. “We know they are paying attention to our messages,” the senior administration official said. “We don’t know if it’s changing their minds.” That is keeping the administration on edge. U.S. military officials have oscillated between fearing a larger Iranian response than its April barrage to Tehran not responding at all. That indecision is based in part on Iran’s military posture, which “definitely doesn’t look like it did before April 13,” a defence official said Thursday.

This month the U.S. sent a squadron of F-22 Raptors to the region. And the USS Abraham Lincoln carrier strike group is moving from the Asia Pacific region to the Middle East, arriving in the coming weeks, U.S. defence officials said. The Lincoln carries F-35 jet fighters and will overlap with the USS Theodore Roosevelt, which is currently operating off the Gulf of Aden.

It is unclear whether any of these moves by the Biden administration will work as intended.

Dana Stroul, who last year left her post as the Pentagon’s top civilian for the Middle East, said Iran is unlikely to cease its aggressive behaviour because the regime doesn’t believe its own security is in jeopardy.

“By over messaging the desire to prevent full-scale war, Iran has interpreted this as a U.S. lack of will to take offensive action,” she said.

The Wall St Journal

As the prospect of an Iranian attack on Israel looms, officials in Washington and Tehran are facing a potential escalation with major risks for both sides.