The conservative legal push to overturn Roe v Wade was 50 years in the making

For the anti-abortion movement that has helped power Republican political success, the end of Roe was a key goal.

The overruling of Roe v Wade was 50 years in the making — the culmination of a conservative judicial movement that rejected the interpretation of constitutional rights underpinning that 1973 Supreme Court decision.

It took far longer than many conservatives expected.

The majority opinion in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organisation, first disclosed in draft version by an extraordinary leak in May, declared that Roe and later abortion-rights precedents have no basis in the Constitution. “The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision,” Justice Samuel Alito wrote for the court, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

Even as a young lawyer, Justice Alito had looked for ways to push back on the reasoning behind Roe going back to the 1980s, when he worked in the Reagan Justice Department. In a May 1985 memo, he sketched out opportunities “to advance the goals of bringing about the eventual overruling of Roe v Wade.”

Former Attorney-General Edwin Meese III championed the conservative jurisprudence during the Reagan years and promoted the young lawyers — Justice Alito among them — who would rise to influence through successive Republican administrations.

“It really has been a matter of pretty clear record for a long time that [Roe] was wrong,” he said. Because the Constitution doesn’t expressly grant women a right to end a pregnancy, many conservatives, like Mr Meese, have said the court erred by construing a right to privacy that allows for abortion at least in the earlier stages of gestation. That originalist legal view overlapped with the convictions of a broader set of people who opposed abortion on what they considered moral grounds as the taking of a life.

Friday’s liberal dissenters pointed to a different constitutional tradition, one that has seen rights expand since the country’s beginnings. The framers “understood that the world changes. So they did not define rights by reference to the specific practices” of their time but “defined rights in general terms, to permit future evolution in their scope and meaning,” Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan wrote in a joint opinion.

For the anti-abortion movement that has helped power Republican political success — including the 2016 election of Donald Trump, who as president appointed three justices who were in the Dobbs majority — the end of Roe was long a key goal. With states now free to regulate the procedure, most abortions likely will be outlawed or at least curbed in about half the states.

But for the conservative legal movement, “this was not a matter of deciding whether abortion is a good idea or a bad idea,” said Mr Meese, now 90 years old. “It’s a matter of the Constitution.”

Counter-revolution

That Roe would stoke a legal counter-revolution leading to its own undoing was far from evident in January 1973, when by a 7-2 vote the Supreme Court recognised a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy before foetal viability, or the capacity to live outside the womb. The decision invalidated dozens of state laws banning or restricting abortion, many dating from the 19th century.

The decision followed a line of cases that had steadily removed the government from regulation of family life and sexual practices. In the Roe opinion, Justice Harry Blackmun cited a series of earlier decisions. It began in the 19th century, he wrote, when the court rejected Union Pacific’s demand that a female passenger, who was suing the railroad for negligence after an upper berth fell on her, submit to a surgical examination.

“No right is held more sacred, or is more carefully guarded by the common law, than the right of every individual to the possession and control of his own person,” the court said in 1891, a year after Louis Brandeis, a future justice, co-wrote a seminal article in the Harvard Law Review, “The Right to Privacy.”

Justice William O. Douglas had invoked that legal tradition in Griswold v Connecticut, a 1965 decision striking down an 1879 state law banning contraception. The “marriage relation” involves “a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights, older than our political parties, older than our school system,” he wrote.

Justice Hugo Black was among those who disagreed. “I like my privacy as well as the next one,” he wrote in his Griswold dissent, “but I am nevertheless compelled to admit that government has a right to invade it unless prohibited by some specific constitutional provision.” The lack of such a named provision has been underlying judicial opposition to Roe v Wade ever since.

In a passage that Justice Antonin Scalia later called “garbage,” Justice Douglas wrote that “specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.”

In that context Justice Blackmun wrote in his 1973 Roe decision that the right of privacy was not only grounded in the Constitution, but also “broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” That right wasn’t absolute, he added, and “at some point in pregnancy” government may “assert important interests” that include “protecting potential life.” Following a 1972 lower court decision invalidating Connecticut’s abortion ban, Roe drew the line at viability, generally seen as between 22 and 24 weeks.

While even some conservative commentators praised the decision, the legal substance of the ruling came under some criticism — including from some liberal-leaning scholars who supported a woman’s right to an abortion. Like Justice William Rehnquist, who dissented from Roe, Yale professor John Hart Ely likened the decision to the 1905 case of Lochner v New York, which struck down a state law limiting working hours for bakers with the argument that it violated a different unenumerated right the court found implicit in the Constitution: the “liberty of contract.”

That precedent, which jeopardised a swath of state laws over workers’ safety and fair treatment, had been effectively abandoned by a series of decisions over the ensuing half-century. “Roe may turn out to be the more dangerous precedent,” Ely wrote, adding: “I suppose there is nothing to prevent one from using the word ‘privacy’ to mean the freedom to live one’s life without governmental interference. But the Court obviously does not so use the term. Nor could it, for such a right is at stake in every case.”

In response to Roe, abortion opponents initially focused on amending the Constitution. Republican Larry Hogan Sr, the father of Maryland’s current governor, proposed within days of the Supreme Court’s opinion an amendment extending due-process and equal-protection rights to “any human being, from the moment of conception” — effectively equating abortion with murder. When such proposals died in Congress, activists turned to the states. By 1981, more than a dozen legislatures, including Massachusetts and Mississippi, had passed resolutions calling for a constitutional convention to consider a human-life amendment. The movement stalled short of the 38 necessary states.

Remaking the judiciary became a central strategy for reversing Roe when Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, amid a broader effort to move federal courts against what Mr Meese called the “radical egalitarianism and expansive civil libertarianism” the justices had embraced in the 1950s and ’60s. In that era, the court under Chief Justice Earl Warren took steps to abolish racial segregation, end government censorship, extend voting rights and increase protections for criminal defendants, as well as rulings like Griswold that defined a broader concept of privacy and individual rights.

Conservatives argued that in those decisions the justices sometimes overstepped their authority to remake society as they pleased.

‘Policy choices’

As an adviser and attorney general, Mr Meese, who had been an aide to Reagan since his tenure as governor of California, was the president’s point man in trying to reverse that pattern. In a 1985 speech to the American Bar Association, Mr Meese called for “a jurisprudence of Original Intention” to counter Supreme Court decisions he said were “more policy choices than articulations of constitutional principle.”

That tenet drew the support of the law students and professors who in 1982 founded the Federalist Society. “There has been a war going on for 40 years, since Ronald Reagan became president, over the role of the Supreme Court in making up constitutional rights,” said one of them, Steven Calabresi, now a law professor at Northwestern University. “The abortion right was the quintessential made-up right.”

Courts have always looked to the framers’ understanding of constitutional provisions, and not always to conservative ends. The liberal-leaning Justice Black, a Franklin Roosevelt appointee, argued that the 14th Amendment was intended to hold states to the same civil liberties rules that bound the federal government.

Mr Meese’s arguments found few takers on the left. Justice Brennan, who had been appointed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and became a liberal stalwart on the court, dismissed the originalist idea several months later in an address at Georgetown University. “It is arrogant to pretend that from our vantage we can gauge accurately the intent of the Framers on application of principle to specific, contemporary questions,” he said.

For judicial appointments, Mr Reagan looked first to tested veterans of the Nixon administration, including Antonin Scalia and Robert Bork, who were named to appeals courts in anticipation of Supreme Court vacancies. He was aided in that by the Federalist Society. The Federalist Society, along with other conservative legal groups, succeeded both by popularising its ideas and preparing its adherents to implement them, said Amanda Hollis-Brusky, a professor of politics at Pomona College. “There was a very concerted focus on how to mainstream ideas about originalism, and conservative and libertarian beliefs about the regulatory state,” she said.

By building chapters at law schools and promoting lawyers through judicial clerkships with like-minded judges, conservative activists prepared a cadre to challenge prevailing directions of constitutional law, Ms Hollis-Brusky said.

In 1986, the Senate confirmed Justice Scalia by a 98-0 vote, including all 47 Democratic senators. Mr Reagan’s nomination of Judge Bork the following year was a jolt to liberals. Joe Biden, then chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, fought to defeat the nomination, principally because Judge Bork rejected recognition of rights such as privacy that aren’t explicitly mentioned in the Constitution. The nomination failed on a 58-42 vote, with six Republicans joining 52 of 54 Democrats.

The bitter partisan battle over Judge Bork, who had addressed the Federalists’ founding convention, forged deeper cohesion among socially conservative jurists and set the stage for more politicised battles over Supreme Court nominations.

Roe’s end

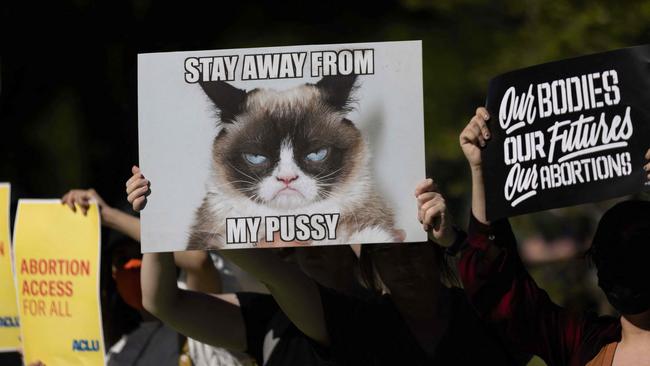

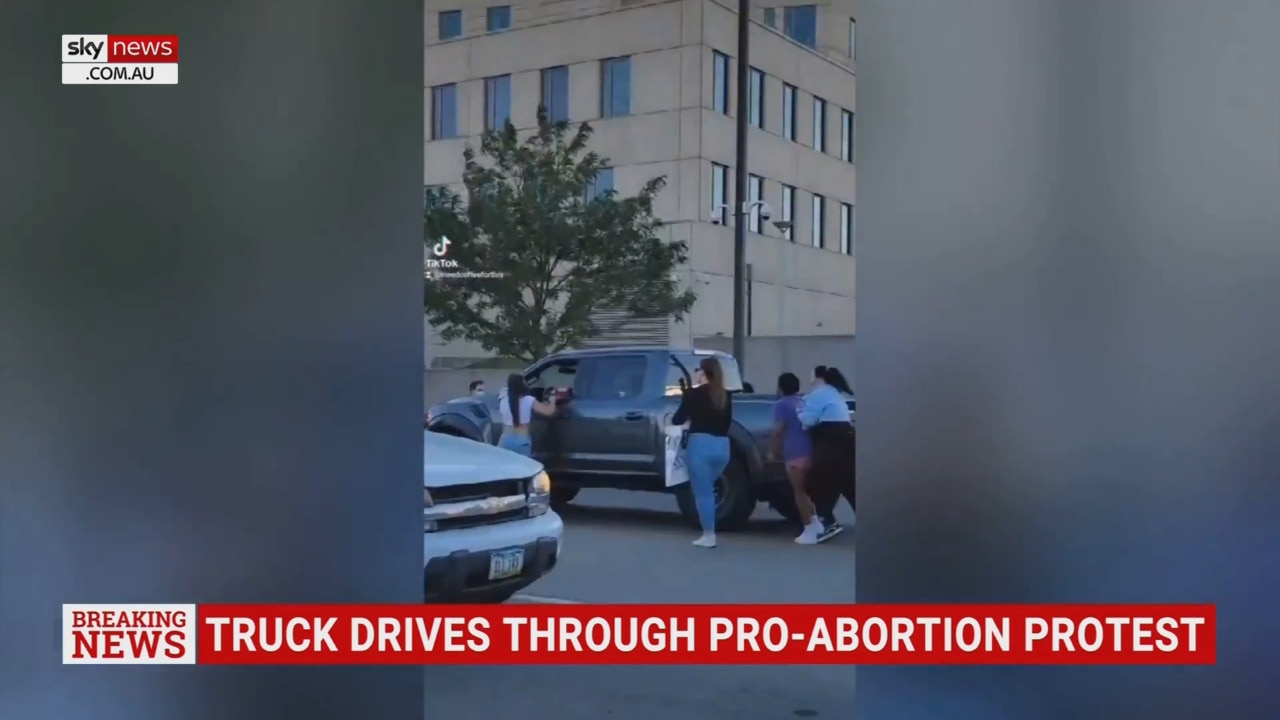

Today, the Supreme Court not only reversed nearly 50 years of precedent, it relegated the most intensely personal decision someone can make to the whims of politicians and ideologues—attacking the essential freedoms of millions of Americans.

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) June 24, 2022

In 1992, when a challenge to Pennsylvania abortion regulations reached the court, Roe’s end appeared possible. Only Justice Blackmun remained from the Roe majority, alongside the two dissenters, Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Byron White. Two recent nominees of President George H.W. Bush joined four other Republican-appointed justices.

Instead, in Planned Parenthood v Casey, a plurality including three of those justices — Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy and David Souter — stepped in to rescue Roe, curbing the decision’s scope but leaving intact the right to end a pregnancy before viability.

While expressing concerns over Roe’s reasoning, they argued that after nearly 20 years, the abortion right was too firmly established to rescind outright.

“An entire generation has come of age free to assume Roe’s concept of liberty in defining the capacity of women to act in society, and to make reproductive decisions,” the plurality said, over a four-justice dissent. “The ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives.”

“Now, just when so many expected the darkness to fall, the flame has grown bright,” Justice Blackmun wrote in concurrence.

During the 1990s, as President Bill Clinton filled the next two high-court vacancies with Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, both committed to abortion rights, the Federalist Society and its allies at law schools and on the bench prepared for the future.

By the time Republicans regained the appointment power under President George W. Bush, the conservative legal movement had become a mature pillar of the legal establishment. The Federalist Society has grown from its law-school origins into a Washington-headquartered non-profit with more than 60,000 members and annual revenue of more than $22 million, 90% of which it says comes from contributions from individuals and foundations. President Bush appointed Justice Alito to the Supreme Court, as well as Chief Justice John Roberts.

President Barack Obama would go on to appoint two liberal judges, Justices Sotomayor and Kagan. Following the death of Justice Scalia in February 2016, the Republican Senate majority refused to hold a hearing or vote on the nomination of Mr Obama’s next judicial nominee, Merrick Garland. The seat went unfilled until the following year and the next presidential administration, when President Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch, who joined the court in April 2017.

It wasn’t until the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy the following year, however, that Roe’s reversal became plausible. For years the court’s swing vote, Justice Kennedy had permitted some abortion restrictions to take effect while retaining the view that the Constitution affords women some power over whether to continue a pregnancy.

Mr Trump had expressly promised to select his successor from a list vetted by the Federalist Society.

Justice Kennedy’s successor, Brett Kavanaugh, had praised Justice Rehnquist’s Roe dissent. But even as he appeared to tip the balance, Chief Justice Roberts, who has expressed a stronger respect for precedent than other conservative justices in recent years, appeared reluctant to rescind a right recognised for nearly half a century. In June 2020, he voted with the court’s liberals to strike down a Louisiana abortion regulation, writing that a 2016 precedent compelled that result even though he had dissented from the prior case.

The following September, the death of Justice Ginsburg allowed Mr Trump to appoint Justice Barrett shortly before he lost the presidential election to Mr Biden.

Until then, abortion opponents had followed a tactic of seeking to erode abortion rights, since abolishing them appeared out of reach. In March 2020, when Justice Ginsburg still sat on the court, Mississippi had appealed lower-court decisions striking down its 2018 law banning most abortions after 15 weeks — an assault on the viability line established in Roe and Casey that advocates hoped could garner five votes.

In 2021, with Justice Barrett on the court, Mississippi Attorney-General Lynn Fitch brought in a new state solicitor general to argue the case. Scott Stewart, a former law clerk to Justice Thomas who had served in the Trump Justice Department, recalibrated the state’s arguments to aim at the ultimate goal.

“Roe and Casey are egregiously wrong,” his brief for the state said. “The conclusion that abortion is a constitutional right has no basis in text, structure, history, or tradition.” That the Supreme Court has now agreed with that statement was no accident, said Mr Meese, hailed by Mr Calabresi as “the unsung hero” of the conservative legal movement. It was the fruition of seeds Mr Meese said he helped plant long ago: “We’ve got people appointed [to the Supreme Court] who are definitely constitutionally oriented lawyers.”

DOW JONES