The complicated mourning of Brian Thompson and the lionisation of Luigi Mangione

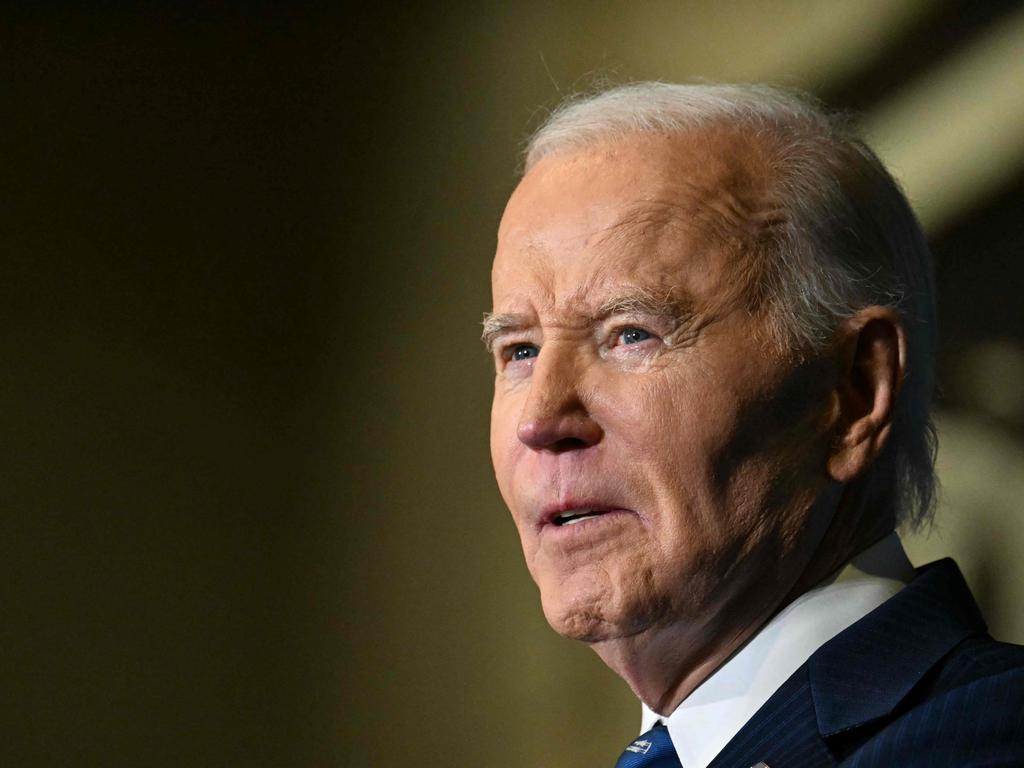

The United Healthcare chief executive’s assassination transformed him from a largely unknown executive to a potent symbol for the frustration many Americans feel towards healthcare.

Friends and colleagues say they are reeling from both the sudden loss of slain United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson and the lionisation of the man accused of killing him.

During Wednesday’s trivia night at Scoreboard Bar & Grill, a mile from the company’s Minnetonka, Minnesota headquarters, bartender Dee Dee Anderson felt the absence of one of her favorite customers.

Thompson, or “BT”, was known as an affable guy who often stopped by with colleagues for nachos at happy hour, preferred frosty mugs for his beer and didn’t get irritated when orders backed up in the kitchen, she said.

The next morning in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania marked a different remembrance. A handful of people, some dressed as Luigi from the Super Mario videogame series, cheered on the very man accused of killing Thompson. Defendant Luigi Mangione was at back-to-back hearings on state charges and his extradition to New York.

One of his supporters carried a sign reading, “Privatized healthcare is a crime against humanity.” A cold dichotomy faces those mourning Thompson. “There’s no connection to the fact that he was a person,” Ms Anderson said.

With his death on a Midtown Manhattan sidewalk on December 4, Thompson was transformed from a highly paid executive unknown to most Americans into a potent symbol for the frustration many people feel about the cost of healthcare and their access to it.

An Emerson College poll of 1,000 registered voters released Tuesday found that while 68pc of people overall called Thompson’s assassination unacceptable, 41pc of those ages 18 to 29 considered the shooting either somewhat or completely acceptable, and 19pc of voters in this age group were “neutral” – a result that dumbfounded one of Thompson’s former colleagues. “I’m just disappointed that anybody feels that a shooting is appropriate, and that type of shooting most especially. That’s just crazy,” he said.

“My perspective is that Brian worked all of his life to make healthcare better.”

Last weekend on “Saturday Night Live,” comedian Chris Rock drew laughter and applause when he said, “I have real condolences for the healthcare CEO. I mean, this is a real person, you know? But you also got to go, you know, sometimes drug dealers get shot.”

Meanwhile, sarcasm abounds on social media. “My deepest thoughts and deductibles to the family,” one TikTok poster wrote. “Unfortunately my condolences are out-of-network and it isn’t deemed medically necessary.”

Heartland success

Thompson, 50, left behind two teenage sons. His wife and other family members declined requests for comment citing the intense public attention the case has attracted. Authorities and companies harbor widespread fear that Thompson’s death could inspire copycat attacks: A Florida woman was recently criminally charged with threatening her insurer after using the words “delay,” “deny” and “depose” on a recorded call. Those words were written on shell casings recovered where Thompson was shot, according to a federal complaint unsealed Thursday charging Mangione with the executive’s murder.

The complaint said Mangione stalked Thompson for more than a week and aimed to send a message about the evils of American corporations. Mangione had written in a notebook months before the shooting that he chose a target in the insurance industry because it “checks every box,” the complaint said.

Thompson was a heartland success story. He’d grown up on a farm in Jewell, Iowa, where his father worked with grain elevators and his mother was a hairdresser. He’d been valedictorian and homecoming king in his high-school class of roughly 50 students. He went on to graduate with honors from the University of Iowa before ascending the corporate ladder at UnitedHealthcare, where his total annual compensation over the past three years averaged $9.9 million.

Legal troubles shadowed his recent past. Thompson was one of three company executives named in a lawsuit from a Florida pension fund in May, alleging UnitedHealth concealed a Justice Department antitrust investigation from shareholders while insiders sold stock – including $15 million in Thompson’s personally held shares. He hadn’t answered the claims in court before he was killed.

He was well-regarded by investors and analysts, who credited him with the growth in UnitedHealth’s powerful, and lucrative, Medicare business. Thompson, who had an accounting background, was known for having an easygoing approach as he climbed the leadership ranks.

He chewed gum, and while CEO he was called out at least once for it by a colleague during a conversation with employees. He wore quarter-zip pullovers or a sportcoat over a button-down shirt with no tie. He dropped F-bombs.

“By the way, I swear a lot,” he once said on a work video. “So if you’re offended, I don’t know if I can do much about it.”

Targeting an industry

Health insurers are broadly unpopular and have been for a long time. Many Americans in a moment of need have had to fight for, or been denied, care by insurers whose mandate to maximize profit is an incentive to limit approvals. Hospitals, on the other hand, have a profit motive to overprovide care, in some ways leaving insurers to police spending.

Consumers’ chief complaint is the aggravation, time and expense of persuading insurance companies to approve and pay for treatment. MRI scans and other vital but costly procedures, even when ultimately approved, often require days of campaigning and paperwork from patients and doctors.

Robert Sterling, a 39-year-old mergers-and-acquisitions consultant based in Wichita, Kansas, was on a plane on December 11 when he dashed off a post on X lauding Thompson. “This guy – not the person who murdered him in cold blood – was everything that’s right and good about America, and the American dream,” he wrote.

He was shocked when he checked his X account hours later and found thousands of mostly critical replies, some saying that Hitler and Stalin also came from humble roots. Mr Sterling said he was reminded of being a student in 1999 when the mass shooting happened at Columbine High School in Colorado, an event he views as the start of a violence phenomenon that now feels all too commonplace. Sterling previously worked at Cargill, one of the world’s biggest food suppliers, and often works with executives in agriculture and energy.

“I pictured my friends in industries that might be polarising, whether it should be or not, and thought, ‘That could be a friend of mine, that’s the next victim here.’ ”

A dad in the bleachers

The vilification of Thompson that proliferated online after his killing “is the exact opposite of what the guy was about,” said his former UnitedHealth colleague. He urged people not to make snap judgments based on what they see and hear, and said he hopes “people’s better sides might come out” as they learn more about Thompson’s efforts in the health insurance arena.

As the Covid-19 pandemic intensified in early 2020, the federal government asked UnitedHealth to help distribute billions in emergency funding to healthcare providers seeking assistance under the Cares Act. The request landed on the desk of Thompson, who was running the company’s Medicare division at the time.

“He immediately told the government we would do that for free. Why? Because we wanted to make sure people had access during Covid,” his former associate said. “There’s no better example of somebody wanting to do right by healthcare than that.”

Thompson was key to making sure 300,000 hospitals and physicians got cash infusions, that by late May 2020 totaled $95bn, recalled Stephen Parente, a University of Minnesota finance professor who was then chief economist for health policy at the White House.

“He was calm, he was self-effacing. You always had the sense this is going to work out,” Mr Parente said, recalling their many late-night and early-morning virtual meetings.

“When it really counted, the guy stood up.”

Thompson had a knack for practical decision-making and a plain-spoken collegiality, whether engaging customer service representatives, Fortune 500 executives or elected officials, the former UnitedHealth colleague said. Thompson embraced the “triple aim” of better outcomes, lower costs and better experience, according to this co-worker, and would ask colleagues, “Would we be proud to have your mother have that experience?”

Away from work, Thompson cherished time with his sons, the former colleague said. They bonded over the Minnesota Timberwolves’ strong NBA season last year. Thompson also made a point of being “a dad in the bleachers” at his sons’ own sports games.

“He really wanted to be able to have his boys look up and see him in the bleachers,” the former colleague said.

Thompson’s rural Iowa roots seemed to stay with him during his two-plus decades at UnitedHealth. “I try not to draw too many distinctions between work and life, and maybe that’s growing up on a farm in Iowa,” Thompson said, according to material provided by UnitedHealth.

“I didn’t grow up in a setting where these things were separate.”

Taking complaints to the CEO

Some of Thompson’s comments reflected an appreciation for customers’ frustrations, which he said he was working to ease.

“I wish healthcare, I wish we, I wish I served up solutions that were clear-cut, which are easy to understand, and easy to explain,” he said in one meeting. He struck a similar note at last year’s investors conference, telling his audience, “Healthcare should be easier for people. We are cognisant of the challenges.”

Over the years, some customers reached out directly to Thompson, including in the comment section of a LinkedIn post he wrote last year about the importance of keeping costs down. Cale Ferland, a branch manager for a mortgage provider in Connecticut, told Thompson he had spent an hour trying to get basic information for his wife, Christy, a 45-year-old mother of four with stage 4 lung cancer.

“I’d love to share my experience with you,” Mr Ferland wrote, providing his phone number.

In an interview, Mr Ferland said he had been trying to get coverage for a $1,500 wig his wife’s doctors prescribed as she entered a moonshot round of chemotherapy.

His wife had long straight blond hair that she took pride in, he said, and losing it dealt a particular blow. He never got a response to his post; she died a few months later.

He was stunned to hear of Thompson’s assassination.

“No one deserves that fate,” Mr Ferland said, “regardless of what’s happened in the business side of things.”

Jon Kamp contributed to this article.

Wall Street Journal