First, a rematch would be only the second time in US history – the other was 1892 – that an incumbent president faced the man he defeated in the prior election. This rare circumstance will transform the race.

When incumbents face challengers who haven’t served as president, the election is mainly a referendum on the president’s performance. Voters first typically decide whether the incumbent has done well enough to merit re-election. If they decide he hasn’t, they then must decide whether they are willing to entrust the Oval Office to his opponent. (Even Ronald Reagan, during his 1980 race against the unpopular incumbent Jimmy Carter, had to reassure voters that he was a safe choice.)

But when a president faces a former president, each has a record to defend, and the election is a choice between comparable options. Each candidate’s agenda for the future can be weighed against his past performance, and voters will view promises to accomplish more than what each candidate did over his previous four-year term with scepticism.

A second key difference between 2024 and typical elections: If Mr Biden is the Democratic nominee, he will probably face a challenge unlike any Democratic incumbent since 1948 – namely, breakaway candidacies from both his left and his right. Harry S. Truman had to surmount challenges from both former Vice President Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party and Senator Strom Thurmond’s Dixiecrats. In 2024 Mr Biden may contend with the Green Party’s Cornel West as well as a bipartisan centrist No Labels ticket. Although Truman lost nearly 5% of the popular vote to the breakaway candidacies, he nonetheless received nearly 50% of the popular vote and handily defeated Republican Thomas Dewey.

With the political parties more balanced today than in 1948, Mr Biden would be harder-pressed than Truman to survive a four-way race. He had to reunify the Democratic Party, which had splintered four years earlier during the bitter primary contest between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, to beat Mr Trump in 2020.

Third, Donald Trump is facing an unprecedented set of legal challenges – multiple criminal indictments that could have him shuttling back and forth between court appearances and campaign events. Massive legal fees are draining funds from his campaign coffers, and this burden is unlikely to decrease between now and 2024. So far, his legal troubles have broadened and intensified his support with the Republican base, but it’s hard to predict what effect they will have on the swing voters who will determine the outcome of the general election.

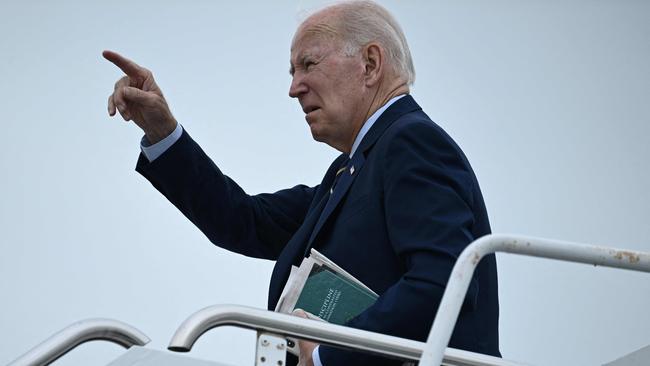

Fourth: When the general-election campaign begins next summer, Mr Biden will be 81 and Mr Trump 78. Already in 2020 they were the oldest nominees ever. While polls suggest that Mr Biden’s age is seen as more of a problem than Mr Trump’s, the actuarial tables indicate that each man is at heightened risk for a serious health event that could transform the contest and even force his party to select an alternative presidential candidate.

After the 1972 Democratic convention, the revelation of vice-presidential nominee Thomas Eagleton’s past episodes of depression forced George McGovern, the party’s nominee for president, to replace his running mate. Selecting a new presidential nominee on short notice would be far more difficult – and consequential – but the odds of such an event next year are higher than in any previous election cycle.

The possible fifth factor: We are living in an unprecedented era of close presidential elections. In the 17 races between 1920 and 1984, the winner prevailed in the popular vote by 10 points or more on 10 occasions, and by 20 points or more five times. In the nine elections since, no winner has come close to a 10-point margin of victory, and on two occasions the candidate with a plurality of the popular vote lost the Electoral College. During this period, the number of truly contested swing states declined sharply, to only eight by 2020. A shift of 43,000 votes in Wisconsin, Georgia and Arizona, states Mr Biden carried by wafer-thin margins, would have yielded a tie in the Electoral College, throwing the election to the House for the first time since the 1824 election.

Public opinion surveys thus far are pointing to yet another close contest whose outcome will be determined by narrow margins in the same states that became the sites of postelection legal struggles four years ago. Until the American people decide to award one party a majority that extends beyond a single presidency, today’s challenges to effective governance and national unity are all but certain to persist.

The Wall Street Journal

It is likely, though not certain, that the 2024 general election will be a rematch between Joe Biden and Donald Trump. If so, the contest will break new ground in at least four important ways, and perhaps a fifth.