Tequila wars: inside the gold mine of blue agave

We’ve come to associate Mexican cartels with drugs and bloodcurdling slaughter. But in the early 1900s, Mexico’s first cartel was formed around tequila.

We’ve come to associate Mexican cartels with the manufacturing and smuggling of drugs, as well as with bloodcurdling slaughter. But in the early 1900s, Mexico’s first cartel was formed around a product that was relatively benign: tequila, the national spirit distilled from the pulped core of the blue agave plant.

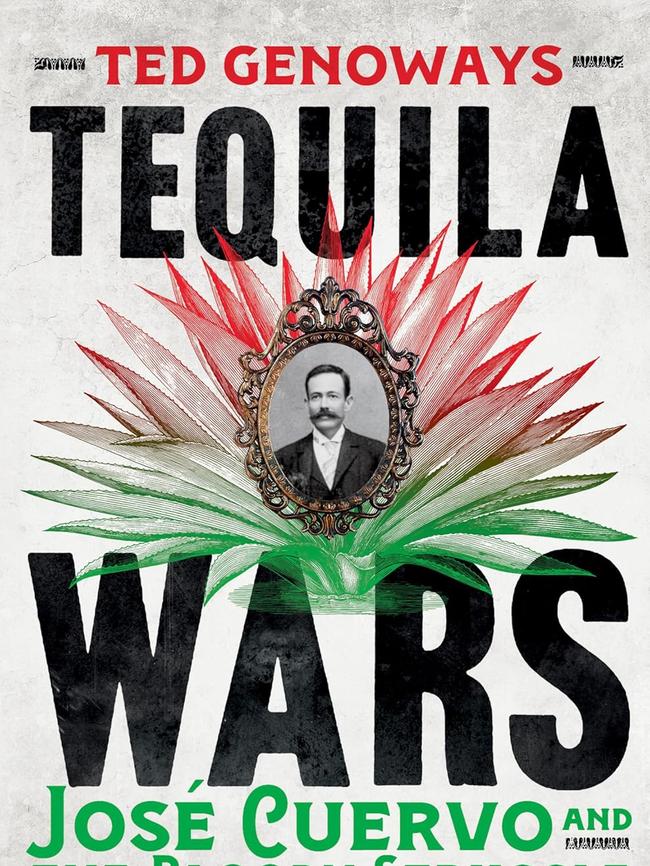

The syndicate was the brainchild of José Cuervo (1869-1921), who gave his name to what is today the world’s best-selling brand of the drink, with a lock on as much as a third of the market.

In Tequila Wars, Ted Genoways tells the story of Cuervo and how he audaciously transformed a single distillery in his hometown of Tequila, 65km northwest of the city of Guadalajara, into a nationwide business that withstood the violent pressures of Mexico’s politics.

In 1899, Cuervo acquired ownership of the distillery, La Rojeña, when he married the widow of its owner, his great-uncle Jesús Flores. The widow, Ana González Rubio, was considerably younger than Flores, who said to her on his death bed, “if you want the business to prosper after I’m gone, then my nephew would make a fine husband”.

Cuervo was initially hesitant, but the no-nonsense Ana made short work of his resistance. “It is best for us to marry,” she told him.

Genoways, a professor of media studies at the University of Tulsa, is a versatile and industrious non-fiction writer whose output includes books on such subjects as the American meat industry. There has, he tells us, never been a book about Cuervo – which is staggering, given that Cuervo is the undisputed Father of Tequila. This lack of writerly and even academic attention confounds Genoways, who contends that Cuervo is “arguably the most famous name in Mexican history”.

This is a provocative claim. What about the Aztec king Montezuma? Frida Kahlo, the painter? Or businessman Carlos Slim?

Still, there’s no doubt that Cuervo is a historical figure who’s astonishingly unsung, but Tequila Wars is not, strictly, a biography of Cuervo. It also tells the story of the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910 and raged for a decade. Throw in foreign involvement – by Germany and, in particular, the US, both countries eager to safeguard the commercial interests of their own nationals in Mexico – and you have a decade in which the best that Cuervo could hope for was simply to stay afloat.

To do that he kept his head down. “Cuervo so successfully evaded scrutiny, so effectively covered his tracks in the midst of crisis,” Genoways writes, “that he has essentially disappeared from history”.

Another obstacle to writing the story of Cuervo is the lack of contemporary documentation, as warring factions repeatedly burned down town halls and public archives. Genoways concedes that much of the personal detail of this story is derived from the writings of Guadalupe (Lupe) Gallardo, Cuervo’s wife’s unmarried niece, who lived in the Cuervo home as an adoptive daughter. Lupe kept a diary all her life and self-published two books (for family consumption only), precious copies of which are kept at a few American university libraries. “Those books were a vital source,” the author tells us, and, indeed, quotes copiously from Lupe’s girlishly florid – but invaluably informative – writings.

In many ways, the history of Mexico in the first two decades of the 20th century is also a history of tequila. Much of the infrastructure in Jalisco – railways, electricity, roads and improvements in irrigation – came about to serve the needs of tequileros such as Cuervo. It was Cuervo who lobbied tirelessly for rail tracks to extend to the US border, making it easier to ship his product to the thirsty American market. The tracks also suited the government in Mexico City, which used them to ferry troops across the war-torn land – when they weren’t being dynamited by rebels, that is.

Genoways’ narrative teems with a vast cast of characters. It is a dizzying tale – Mexican affairs at the time were mercurial and faction-ridden – and reading the book can, at times, feel like drinking a half-bottle of tequila in a single sitting. The mind grows numb if you’re not already steeped in Mexican arcana, and many details blur. At the centre of it all stands Cuervo, “as an empresario, as a kingmaker, as a cultural force” during “his nation’s most tumultuous and formative period”. Mexico should be grateful to Genoways for bringing him back from the dead.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout