Tensions between Bibi Netanyahu and Kamala Harris

Ms Harris is expected to meet Mr Netanyahu during his visit to Washington, but the snub is unmistakeable. It is fuelling rumours of a rift between the Harris and Biden approaches to the Middle East. On March 4, NBC News reported that National Security Council officials “toned down” a draft of remarks Ms Harris was to give on the humanitarian situation in Gaza. This week the Journal reported that other fissures could appear. Observers will focus on any signs of Biden-Harris tension as the election approaches.

This scrutiny comes at an awkward moment. Some ugly truths are beginning to make themselves felt in Washington. The danger of American involvement in a wider war across the Middle East is dangerously high. Iran has never been closer to a nuclear weapon than it is today, and American officials worry that Vladimir Putin, as part of his anti-Western campaign, might help Iran across the nuclear finish line faster than US or Israeli officials thought possible.

Despite repeated American warnings, Iran hasn’t reined in its Houthi proteges in Yemen, and Washington’s patience is wearing thin. The closing months of the Biden administration could see US forces engaged in direct attacks on Iranian naval vessels or against Iran itself. People in government, former officials and informed observers tell me that the pressure inside the US government for military strikes against Iran is building, and further Houthi provocations are likely to prompt a dramatically stronger response.

Team Biden’s approach to the Middle East hasn’t satisfied many Republican critics, but it represents a significant evolution from former President Barack Obama’s approach. In the Obama years, the goal of American Middle East policy was to achieve regional stability through detente with Iran. Iran optimists hoped that the nuclear deal would be the first of a series of agreements that would gradually ease hostilities between Washington and Tehran and reduce conflict across the region.

Team Biden no longer sees this as viable. Iran’s rejection of President Biden’s offer to re-enter the nuclear deal was sobering. Iran’s expansion of support for proxies and terrorists across the region hammered the message home. Iran wants a hostile relationship with both the US and Israel. However often Charlie Brown takes a run at the football, Lucy is going to snatch it away.

That realisation led Team Biden to re-examine its attitudes toward both Saudi Arabia and Israel. If Iran is irreconcilable, the only route to stability in the Middle East involves a partnership between Israel and conservative Arab states like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Embarrassing as it might be for Bidenites to follow a policy akin to Donald Trump’s Abraham Accords, the US needed to work with the regional players who agreed with us on the basics. Promoting strategic reconciliation between Israel and Saudi Arabia and enshrining that co-operation in a security treaty between Washington and Riyadh became the principal goal of Biden-era Middle East policy.

The day before Hamas’s terror attack on Israel, Team Biden believed that goal was within reach. Since then, the administration’s objective in the region has been to insulate progress on a new security architecture from the political fallout of the Gaza war. While many pro-Israel observers wish that Mr Biden’s support for our embattled ally had gone further, the effort to safeguard the Saudi negotiation has been largely successful. Key Arab states believe that their own economic and security interests depend on strategic alignment with both Israel and the US. As one senior Saudi observed to an American interlocutor, even a coalition of all the other countries in the world couldn’t offer Saudis the economic, technological and security benefits they can gain through deep co-operation with the US.

The chief political obstacles to this realignment aren’t in the Middle East. They are in America. A loose coalition of pro-Palestinian activists, Muslim Brotherhood supporters, Iran sympathisers, Arab democracy advocates, proponents of Obama-style “Iran First” Middle East policy and isolationists oppose the US-Saudi security treaty that would anchor the alignment. Since treaties require a two-thirds majority in the Senate for ratification, minority opposition must be taken seriously. Without the president’s strong support, no US-Saudi treaty would pass.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Disrupting the US-Arab-Israeli entente is Iran’s objective and also is important to Russia and China. All the revisionist powers loathe the idea of a US-led alliance system stabilising the Middle East. A long-term partnership of the Gulf Arabs and their financial muscle with American and Israeli capitalism and technology would tilt the global balance of power against the revisionists.

This is where the Vice-President’s fealty to Zeta Phi Beta matters. Rightly or wrongly, key Arab leaders may interpret her snub of Mr Netanyahu as evidence that Ms Harris sympathises with the opponents of a Saudi treaty and that her Middle East policy will differ significantly from Mr Biden’s. That in turn would make it harder for Biden negotiators to get to yes, either about a Gaza ceasefire or on the final details of the Saudi deal. It may also encourage the Iranians, sensing weakness and division within the administration, to turn up the heat on Mr Biden, increasing the chance of a shooting war in the Gulf.

What vice presidents do doesn’t normally matter much, but Kamala Harris is playing in the big leagues now. The whole world is watching, and she needs to get it right.

The Wall Street Journal

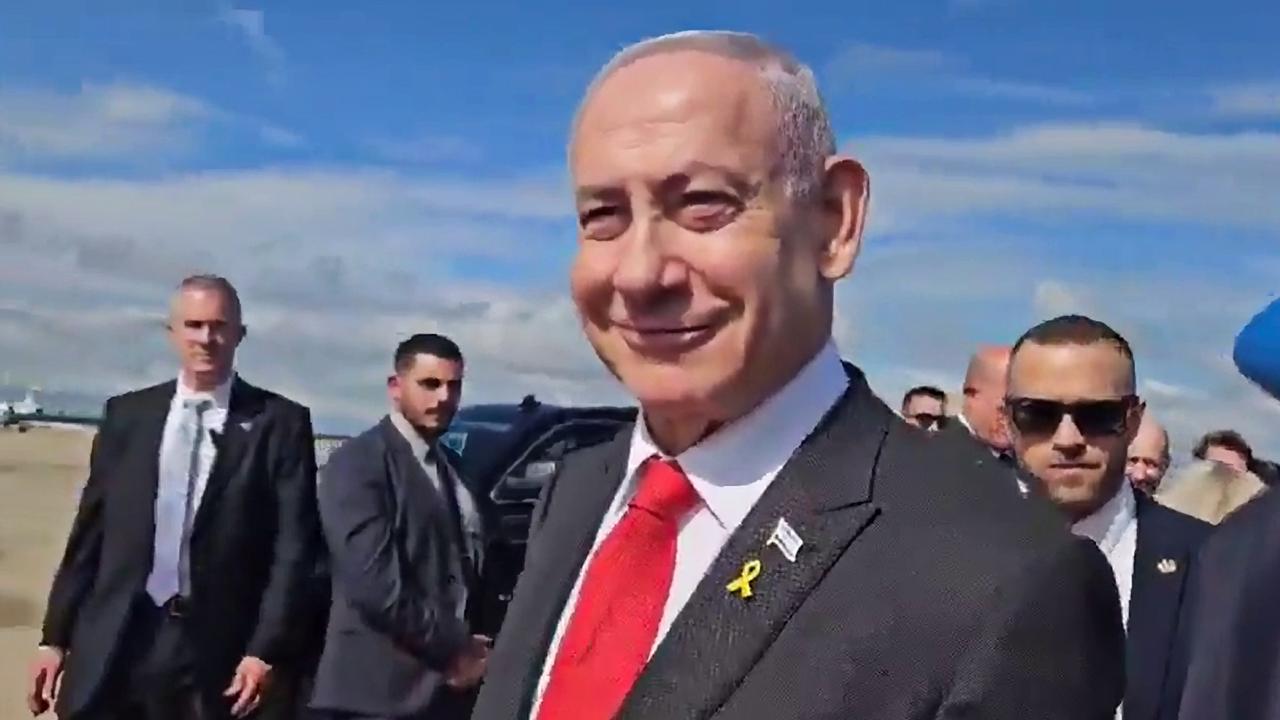

When Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addresses a joint session of congress Wednesday, Vice-President Kamala Harris won’t be there. Despite having become the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, she decided that an earlier commitment to the Zeta Phi Beta sorority’s convention in Indianapolis mattered more than a speech by the leader of one of America’s closest allies at a time of conflict and crisis in a region involving vital US interests.