Sorry, but shale won’t save us from oil crisis

America’s bountiful shale deposits have displaced worries about the far larger oil reserves and production of the Middle East.

America’s bountiful shale deposits have displaced worries about the far larger oil reserves and production of the Middle East. This weekend was a reminder of just how crucial the region remains.

Saudi Arabia’s forced shutdown of more than half of its crude production, some 5 per cent of world supply, should be short but shocking. Energy traders had become complacent about geopolitical risk in part because massive shale plays, particularly the Permian Basin in Texas and New Mexico, have driven growth in world oil production.

The region pumps 4.4 million barrels of oil a day, according to the US Energy Information Administration. Growth over the past 10 years has helped make the US a significant exporter of petroleum products.

Since the 2014 collapse in oil prices at the tail end of an earlier boom in shale output, which was later surpassed in volume, Saudi Arabia and other members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, along with non-member Russia, have struggled to support prices and to adapt to the shale era.

Reinforcing the impression that traditional oil producing heavyweights were no longer as important is shale’s nimbleness. Part of what supported prices after the 2014 price collapse was a reversal in US output by the middle of 2015. Unlike voluntary cutbacks from OPEC producers, this reflected hundreds of individual, commercially driven decisions by drillers. Shale’s short drilling cycle meant that a pullback in investment soon translated into a drop in output.

The flip side of that has seen a surge in output to record levels since prices recovered, much to OPEC’s frustration. This feeds the impression that shale can save the day. But Saturday’s attack should serve as a reminder that this isn’t the case.

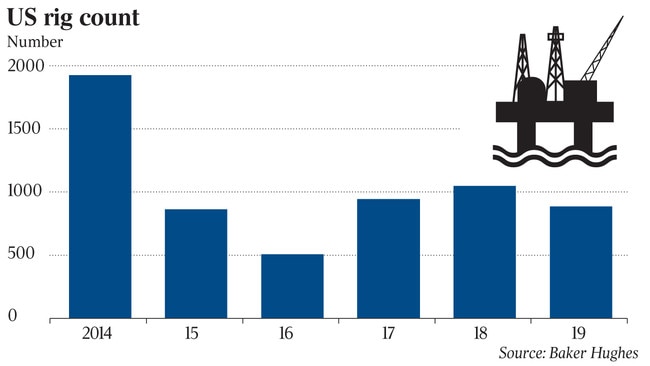

Shale simply can’t respond to an attack on the artery of the world oil market. It can’t even make much money these days. Drillers have been under pressure from shareholders to bolster returns and cut back investment. Permian-focused companies like Pioneer Natural Resources are doing just that. Investment has showed signs of slowing — active US rigs hit a 17-month low in July. The most recent reading from Baker Hughes shows the number of drilling rigs down 16 per cent from last year.

Prices would have to remain high for a long time as a result of the attack to spur a rebound. Yet the orders of magnitude are instructive: Shale can make up for a slow decline in output from, say, once major producer Venezuela, but even a million incremental daily barrels a year from now makes little difference compared with five million barrels lost overnight.

And such projections ignore reality on the ground. Even if more rigs were to come online quickly, the region continues to be hampered by infrastructure bottlenecks. The shale revolution has been a boon to the US economy and to energy consumers everywhere. Markets should adapt to this weekend’s disruptions, but Texas simply can’t ride to the rescue in the event of a more lasting disruption.