Shakespeare set stage for modern political masters

Like the Bard’s Mark Antony and Henry V, real-life politicians rely on rhetoric and stagecraft to achieve their goals.

Most of us dislike performative politics, and for good reason. It is theatre, in a thoroughly negative sense of the term.

But, as Shakespeare teaches us, theatre suffuses all of politics, for better and worse. It is one of the reasons Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill adored him and memorised large swatches of his plays’ famous speeches. It is one of many reasons reading him continues to be an education in politics, including our own.

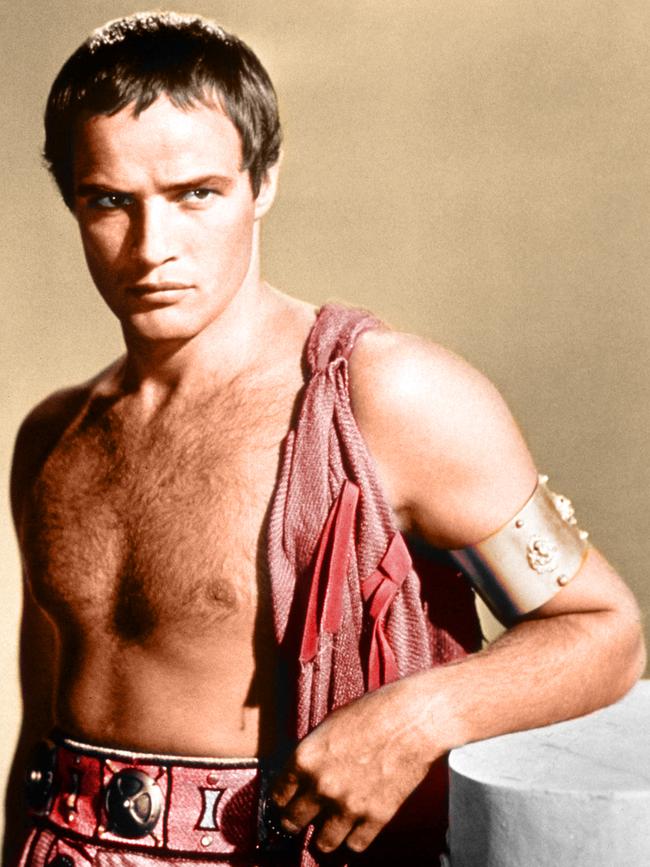

If one wants to learn, for example, how politicians who are intelligent and upright but dull and theatrically clueless can get beaten by a talented demagogue, study the famous scene in Julius Caesar that takes place by the slain dictator’s corpse and before a large, unruly crowd.

Brutus, the reluctant leader of the conspiracy to kill Caesar and thus to prevent him from crushing Roman freedom, insists on some terrible theatrical choices. He marches out his fellow conspirators, their arms bathed in blood, when he actually wants to show they are not butchers. He gives a speech in dull prose rather than stirring poetry, and the word he uses most is “I”. He then leaves the stage to Mark Antony, Caesar’s grieving, cunning and vindictive friend.

Antony, by contrast, not only gives a powerful speech in iambic pentameter, he also uses the body as a prop, gathering the mob around him, saying he will “Show you sweet Caesar’s wounds, poor poor dumb mouths, / And bid them speak for me”.

In an artful speech, artfully delivered, he turns the people to his cause. Consummate actor that he is, in a cynical aside after they go off to burn, murder and riot, he says to the audience: “Mischief, thou art afoot: Take thou what course thou wilt.”

For Shakespeare, politics is theatre, and that’s no less true of modern politics. There is costuming: Think of John F. Kennedy going hatless to his inauguration, thereby drawing a contrast between his youth and vigour and that of his much older and more conventional predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

There is the stage, whether a monumental square or a more intimate fireside. There are the directors – the political bosses and manipulators behind the scenes – and the actors. There’s an audience or, as in Shakespeare’s time, multiple audiences, from the groundlings standing near the stage, delighted by the fight scenes and dirty jokes, to the seated sophisticates revelling in the clever wording. And there are critics, whose equivalents today are journalists and pundits.

Shakespeare’s most brilliant political creation is probably Henry V, the boy king who charms us all even though he launches an unjust war, shuns his dying mentor, Falstaff, and thereby breaks his heart, and orders the execution of an old friend. Henry threatens civilians with appalling prospects of rape and murder, and casually orders the massacre of prisoners. In the biggest hoodwinking of all, he tells his soldiers they and their noble superiors will be a “band of brothers” after the battle of Agincourt. But he quietly confides to the audience that they are fools, slaves and peasants who do not understand how he maintains the peace, while he fights an unnecessary war for his own glory. It’s all one astounding act, and even though we know the truth, we go along with it.

But political theatre can also do enormous good. When Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine on February 24 last year, the acting talents of President Volodomyr Zelensky enabled him to rally not only his people but the entire liberal democratic world to his side. A prominent Shakespeare director once told me the first and most consequential choices he made had to do with costuming and stage set. Zelensky seems to understand this. He appeared that night, as he has thereafter, in olive drab garments that are not precisely a uniform but are clearly the garb of, as Shakespeare’s Henry calls himself, a “warrior for the working day”. He dresses like a civilian commander-in-chief, not pretending to be a generalissimo but obviously focused on his role as a wartime leader.

Zelensky’s stage set that first night of the war was a city street in a Kyiv under attack, with his immediate advisers and subordinates clustered by him. “We are all here,” he said. “Our soldiers are here. The citizens are here, and we are all here. We will defend our independence. That’s how it will go.”

Zelensky’s speech used all the tricks of anaphora, or repetition, that Shakespeare deploys to masterly effect (“We few, we happy few”). Churchill used this simplicity and directness to similar effect in the dark June of 1940, when he said Britain would fight, “if necessary for years, if necessary alone”.

It is a delicate business to use stagecraft without seeming stagy, deploying rhetorical devices without apparent insincerity. Only masters such as Churchill or Zelensky can pull it off. One false slip and the magic of the stage is gone, as dictators frequently discover at the very end. Shakespeare’s brilliantly verbose but incompetent King Richard II discovers his over-the-top invocation of avenging angels has no effect on Henry Bolingbroke, who will depose him, and the hard men around Bolingbroke who will be quite happy to kill him.

At the end, he collapses in a recognition of the reality behind the costume and scenery: “For within the hollow crown / That rounds the mortal temples of a king / Keeps Death his court, and there the antic sits / Scoffing his state and grinning at his pomp.”

It is entertaining and occasionally appalling to see Richard II and Shakespeare villains such as Goneril and Iago on the stage. In the real world of political power, however, one has to work with such people and live with the consequences of their actions. One of the great gifts Shakespeare offers us is an understanding of how they think, how they fool us while also fooling themselves, and how we become consumed by the play in which we find ourselves fascinated spectators.

The Wall Street Journal

Eliot A. Cohen’s The Hollow Crown: Shakespeare on How Leaders Rise, Rule, and Fall is published by Basic Books.