Sam Altman is battling with governments over your eyes

Sam Altman wants to save us from the AI-dominated world he is building by attempting to scan the eyeballs of every person on Earth and pay them with his own cryptocurrency. But world leaders aren’t buying his plan.

Sam Altman wants to save us from the AI-dominated world he is building. The trouble is, governments aren’t buying his plan, which involves an attempt to scan the eyeballs of every person on Earth and pay them with his own cryptocurrency.

Altman’s OpenAI is creating models that may end up outsmarting humans. His Worldcoin initiative says it is addressing a key risk that could follow: We won’t be able to tell people and robots apart.

But Worldcoin has come under assault by authorities over its mission. It has been raided in Hong Kong, blocked in Spain, fined in Argentina and criminally investigated in Kenya. A ruling looms on whether it can keep operating in the European Union.

More than a dozen jurisdictions have either suspended Worldcoin’s operations or looked into its data processing. Among their concerns: How does the Cayman Islands-registered Worldcoin Foundation handle user data, train its algorithms and avoid scanning children?

Altman, the billionaire figurehead of the artificial-intelligence revolution, has tried to push back and open doors for Worldcoin. The project is a lesser-known part of the OpenAI chief executive’s sprawling business empire, but it plays a vital role in his vision for society’s future, by attempting to ascribe all humans a unique signature.

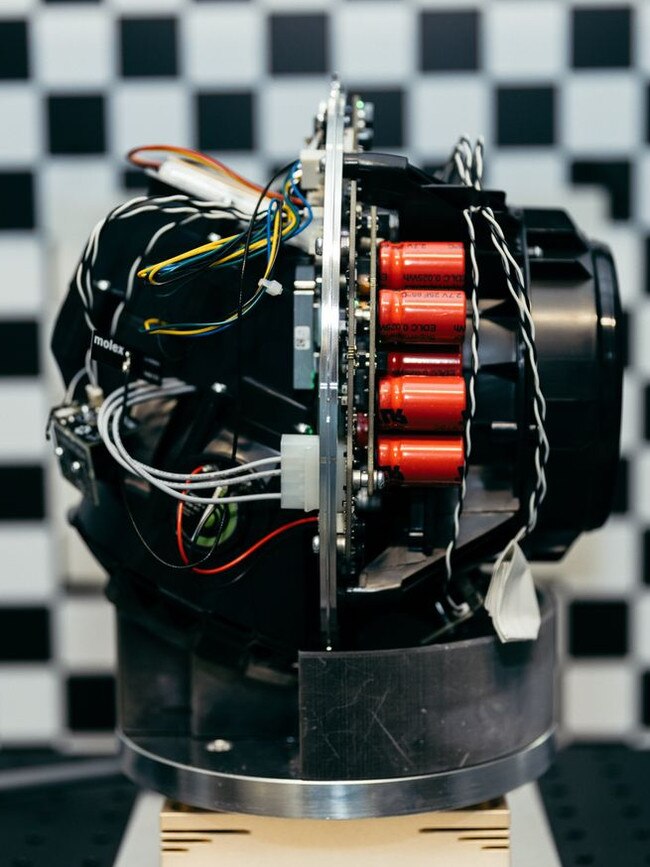

Worldcoin verifies “humanness” by scanning irises using a basketball-sized chrome device called the Orb. Worldcoin says irises, which are complex and relatively unchanging in adults, can better distinguish humans than fingerprints or faces.

Users receive immutable codes held in an online “World ID” passport, to use on other platforms to prove they are human, plus payouts in Worldcoin’s WLD cryptocurrency.

Worldcoin launched last year and says it has verified more than six million people across almost 40 countries. Based on recent trading prices, the total pool of WLD is theoretically worth some $15 billion.

The project says its technology is completely private: Orbs delete all images after verification, and iris codes contain no personal information — unless users permit Worldcoin to train its algorithms with their scans. Encrypted servers hold the anonymised codes and images.

However, several authorities have accused Worldcoin of telling Orb operators, typically independent contractors, to encourage users to hand over iris images. Privacy advocates say these could be used to build a global biometric database with little oversight.

Damien Kieran, the project’s chief privacy officer, said any groundbreaking venture like Worldcoin inevitably draws scrutiny, and the initiative was working with regulators to address concerns.

The project has paused the image-sharing option for users while it develops a new process, he said, and is continually improving its ability to keep people secure. Current training materials don’t ask operators in any way to induce users to share biometric data, he said.

“We’ve built a technology that by default is privacy-enhancing,” Kieran said in an interview. “We don’t collect data to harvest it. We don’t sell data. In fact, we couldn’t sell it, because we don’t know who the data belongs to.”

‘Very advanced and novel technology’

In 2019, Altman conceived the idea of building a technology that could eventually distribute a form of universal basic income to everyone on Earth whose livelihoods would be disrupted by AI.

“I started thinking that it would be quite powerful if you could have the biggest financial and identity network imaginable,” Altman told a podcast last year. He didn’t comment for this article.

The following year, Altman tapped a 26-year-old German called Alex Blania, a former California Institute of Technology researcher.

The founders set up a US company, Tools for Humanity, to build the technology, with Blania as CEO. Blania based much of his team in the Bavarian city of Erlangen, where he had previously studied theoretical physics. A non-profit Cayman foundation, meanwhile, manages the data, tokens and intellectual property.

The project drew controversy soon after becoming public.

Unlike many Silicon Valley start-ups that first expand across the US, Worldcoin was global almost from the get-go, racking up users in less-developed markets like Indonesia, Kenya and Nigeria, and throughout Europe. It hasn’t offered WLD coins in the US, citing an uncertain regulatory environment.

Critics charged Worldcoin with targeting less technically literate places. “It’s taking advantage of people’s lack of sophistication to train very advanced and novel technology,” said Calli Schroeder, a senior counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, a Washington-based non-profit.

Worldcoin says it wanted to test how the Orbs handled different climates and geographies, from dense cities to sparse developing areas.

In Kenya, Altman’s project secured half a million sign-ups within three months of its public launch, but quickly ran into trouble.

Police launched a criminal investigation into the collection of biometric data, interrogating local managers and agents, seizing Orbs in a warehouse raid and summoning foreign representatives through Interpol. Kenya’s parliament held a public inquiry, with Blania jetting in to testify. He and Altman also met Kenya’s president, William Ruto, last year in California.

The parliamentary report said that Kenya’s data commissioner had repeatedly told Worldcoin to stop collecting personal data, citing doubts about user consent, and that a May 2023 cease order wasn’t shared with Orb operators.

After the order, Tools for Humanity addressed the commissioner’s concerns in written replies, describing improved operator training, but kept scanning Kenyans.

Lawmaker Gitonga Mukunji, who initiated the inquiry, compared Worldcoin’s use of “small enticements” to OpenAI, which has relied on low-paid Kenyan workers to train chatbots to avoid toxic content. “These companies pay our population peanuts, and the technology then makes them rich,” Mukunji said in an interview.

The Kenyan public prosecutor’s office closed the criminal case in June, recommending Worldcoin properly register with authorities in future. Tools for Humanity said it would continue to work with Kenya’s government and hoped to resume operations there soon.

Other setbacks followed.

Hong Kong banned Worldcoin, finding it was retaining iris images for up to a decade. Argentine authorities launched investigations, citing a lack of information and what they said were abusive user terms. Spain accused Worldcoin of scanning children at a large scale, while Portugal said Worldcoin taught operators to encourage people to consent to their data’s use.

Authorities in Bavaria, where the foundation has a data-processing subsidiary, have led an EU inquiry into Worldcoin and expect to issue a decision as soon as next month.

The head of the German state’s data regulator, Michael Will, said his team has focused on ensuring iris codes and images are secure, given that biometric data can’t be altered and any breach could lead to identity fraud.

“Once somebody has your specific iris picture, you will never have the possibility to stay anonymous,” Will said.

In response to regulators’ actions, Worldcoin has countered with a global charm offensive and rolled out new measures.

The project’s head of global affairs told Forbes Argentina it had “injected hundreds of millions of dollars into the economy.” Altman, Blania and colleagues then met with Argentine President Javier Milei as he toured Silicon Valley. Worldcoin said it would make Argentina a regional hub, hiring local staff and opening new sites.

Worldcoin operators now check identity cards to deter minors, and the project lets users permanently delete iris codes, a key requirement of EU data-protection rules. A new system breaks up iris codes, with segments held on separate encrypted data stores. Only someone with access to all the servers, and the combination keys, could piece the codes back together, according to Kieran, the privacy chief.

He said the goal is to reach a point where “we couldn’t even get to this data if we wanted to.”

Countering ‘the greatest risk of AI’

Altman has little day-to-day involvement in Worldcoin, executives say. But people familiar with the matter say he holds equity in Tools for Humanity, which also puts him in line to receive WLD tokens.

Worldcoin has racked up other heavyweight backers, raising $240 million from investors including Andreessen Horowitz and Khosla Ventures, according to PitchBook.

Blania has said Worldcoin’s mission is even more urgent given AI is already reshaping the internet, with bots and fake accounts proliferating on social media. Blania says the problems will intensify if AI models emerge with human-level cognition.

“The greatest risk of AI is that it renders the internet an untrustworthy place,” said Lasha Antadze, co-founder of Rarilabs, a US start-up that anonymously verifies online identities by scanning passports. Rarilabs has integrated Worldcoin with its system.

One challenge for Worldcoin: Much of its success hangs on its cryptocurrency. Worldcoin is gradually unlocking tokens allocated for user “grants,” along with the quarter of the total assigned to investors and team members. So far, the foundation still controls 97% of WLD, meaning the price is set by a small pool of currency in circulation. If WLD prices drop, there is less incentive to sign up, because it reduces the dollar value of payouts to users.

WLD is actively traded. But in chat groups where holders gather, the focus centres on using the token to bet on Altman’s other ventures: Its price almost quadrupled just after the February release of OpenAI’s Sora video tool, for instance.

Worldcoin executives say users also make real-world payments with WLD. They point to a Kenyan who said he bought a goat with the tokens and named it Sam.

Álvaro, a drone pilot in the Spanish port of Cádiz, got scanned last year and has received 120 WLD tokens since then. The 34-year-old, who declined to give his surname, said he didn’t fret about Worldcoin’s use of biometrics, reasoning he already handed over similar data to other companies.

“I believe in Sam,” he said, “so I’m holding for the really long term.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout