Rising prices test how much European voters will tolerate cost of sanctions on Russia

The likelihood of a protracted confrontation with Russia is darkening the mood of voters in Europe, where hardliners are now campaigning on surging food and fuel prices.

Surging food and fuel prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are fueling discontent across Europe, testing Western democracies’ political resilience.

The first round of France’s presidential election on Sunday saw right-wing populist Marine Le Pen get 22.9 per cent of the vote on the back of a campaign focused on voters’ dwindling purchasing power. Her far-left rival, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, whose campaign focused on prices, wages and welfare benefits, wasn’t far behind, with 22 per cent of votes.

From France to Spain, Germany and Greece, a combination of near-stagnant wages and rising prices is sparking protests and piling pressure on governments fragilized by years of unpopular Covid-19 restrictions.

The darkening mood raises questions about how much European voters are willing to tolerate the economic costs of what looks likely to become a protracted confrontation with Russia.

Russia accounts for around 40% of the European Union’s imports of natural gas, a key source of energy for the bloc. It also supplies around a quarter of the bloc’s oil imports. While supplies of both have continued to flow from Russia, their prices have risen sharply.

Eurozone energy prices rose 12.5 per cent in March from February, and were 44.7per cent higher than a year earlier, according to the European Union’s statistics agency.

Food prices are also rising rapidly, up 0.9per cent in March and 5per cent from a year earlier, partly driven by concerns about a shortage of wheat and vegetable oil, which Russia and Ukraine produce in large quantities.

Samira Tafat, a podiatrist who lives in the Paris region, spends most of her day at the wheel, making house calls. Her husband is a taxi driver.

“Our fuel budget is huge, it’s become unmanageable,” she said. “I have three children, I need to feed them.”

Some 79per cent of roughly 4000 people polled across France, Germany, Italy and Poland supported economic sanctions against Russia, according to an Ifop survey from early March, while 67per cent supported supplying military equipment to Ukraine.

However, worries about the cost of living are rising. A separate survey by YouGov published last month found 82per cent of Germans expect their household bills to increase over the coming 12 months, alongside 79per cent of Italians and 78per cent of Spaniards.

This economic uncertainty is providing an opportunity for populist parties that remain in the opposition across most of Europe to refocus their public message away from traditional anti-immigration, anti-Islam and law-and-order positions.

In France, Ms Le Pen’s campaign focused on the economic sting of rising inflation. She has held rallies in small rural towns, pledging to slash taxes on fuel and other essentials and to give businesses incentives to raise wages.

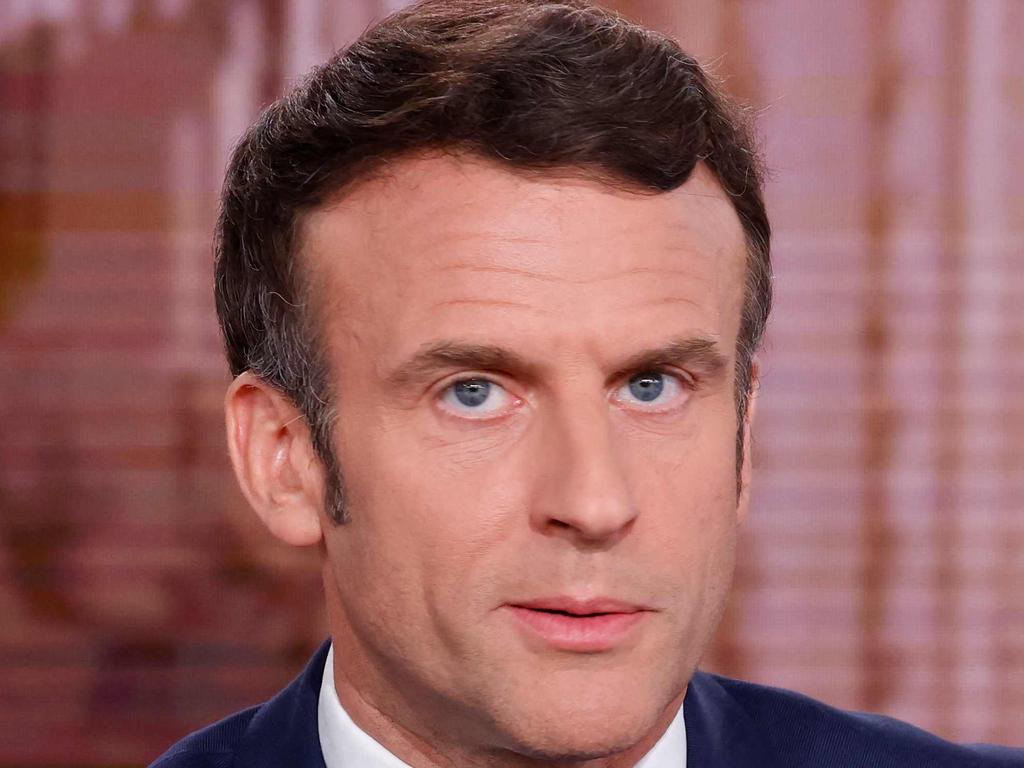

By contrast, President Emmanuel Macron’s advisers said the leader was too busy taking calls with US President Joe Biden and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, about the war in Ukraine to campaign in earnest or debate with his rivals.

Some right-wing populist leaders elsewhere in Europe have echoed Ms Le Pen’s approach. Matteo Salvini, leader of Italy’s anti-immigrant League party, has avoided speaking about the war, focusing instead on taxes and the economy.

Morena Colombi, who works at a cosmetics company near Milan, said her most recent two-month heating bill was 1250 euros, equivalent to around $1361. That compared with EUR450 for the same period last year. She said that even before the war in Ukraine, her salary wasn’t keeping up with inflation.

She used to go out for a pizza with her son or friends about every other weekend, but lately has been doing it once a month. She has cut down on visits to the beautician and resorted to “do it yourself grooming” instead. She has also started shopping at discounters for groceries.

“I’m anxious all the time now because I see prices going up every day,” said Ms Colombi, 61. “Prices go up and the salary is what it is.”

Energy and food price rises hit the poor hardest, because such essentials account for a larger share of their budgets. In Europe, wages haven’t kept pace with inflation, making Europeans poorer in real terms and threatening the region’s post-Covid-19 economic recovery.

In the final three months of 2021, hourly wages were 1.5per cent higher than a year earlier, while the average rate of inflation was 4.7per cent –- a fall in real wages of 3.1per cent.

“Everything is increasing except our salaries,” said Aurélie Karmann, a factory worker and mother of two who lives in Stiring-Wendel, a small town close to France’s border with Germany. “It is becoming very hard.”

A YouGov poll of German consumers released April 3 showed 15.2per cent of respondents said they could no longer afford basic necessities, and 53.4per cent were concerned about rising prices, up 10 points in three months.

Last week, Greece’s two largest labor unions held a nationwide strike to protest rising prices and call for an increase in the minimum wage. The Greek government has spent more than EUR3 billion on offsetting the effects of inflation, for instance, by offering subsidies for power and gas bills.

“Prices are going up everywhere: supermarkets, clothing, water, electricity, gas, heating,” said Frosso Batzi, 51, who works for a clothing company in Greece and is married with two children. “It is getting worse all the time.”

Esther Lynch, deputy secretary-general of the European Trade Union Confederation, which represents 45 million workers, said the level of inflation, not seen since the 1980s, is pushing demands for higher wages.

However, employers are less likely to agree while they also face higher energy costs, weaker demand and, in some cases, fresh disruptions to their supply chains as a result of the war.

Talks between Germany’s IGBCE chemical workers union and employers on a new pay deal were under way when Russian troops crossed into Ukraine. The two agreed Tuesday on an interim solution that gave workers a one-off payment to help with higher energy bills and other costs until a new pay deal is agreed in October.

“In this period of great uncertainty for workers and companies, we had to find a solution that combines inflation relief with job security,” said Michael Vassiliadis, the union’s president.

Wall Street Journal