Rappers’ lyrics are used against them in US courts. The music industry wants it to stop

An industry coalition in the US is urging prosecutors to limit the use of hip-hop lyrics as evidence.

Rappers Young Thug and Gunna are behind bars in Atlanta on gang-related charges after prosecutors used their own lyrics against them as evidence. Now the music industry is speaking out, arguing that rap musicians are being held to a different standard than other artists when it comes to the use of lyrics in court.

A broad coalition led by Warner Music Group, the third-biggest music conglomerate and parent of the rappers’ distributor, 300 Entertainment, placed an open letter in The New York Times and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Tuesday. It urges prosecutors and federal and state legislators to limit the use of rap lyrics as evidence on the grounds that it unfairly prejudices juries against defendants.

Signatories include rival music conglomerates Universal Music Group and Sony Music Group; concert-promotion giants Live Nation Entertainment and AEG Presents; and platforms like Spotify and TikTok. A lengthy list of artists such as Drake, Coldplay and Camila Cabello also signed the letter.

“We’re the only art form that has been attacked like this,” says Kevin Liles, chairman and CEO of 300 Elektra Entertainment, which is part of Warner Music Group.

Young Thug, one of the most influential rappers of the past decade, and Gunna were indicted in May on racketeering charges, with prosecutors calling their “YSL” collective a “criminal street gang”. The indictment, which cites lyrics and social-media posts, alleges that members of the collective were involved in murder, armed robbery, drug dealing and other crimes. One Young Thug lyric included in the indictment is: “I’m prepared to take them down.” The two rappers, who deny the charges, have been denied bond and are awaiting a trial.

Jeff DiSantis, a spokesman for Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, who is overseeing the case, says: “The only time we’ve used lyrics in any indictment is as it related to specific crimes in the indictment.”

“If you decide to admit your crimes over a beat, I’m going to use it,” Ms Willis said at an August press conference. “I have some legal advice, ” she said. “Don’t confess to crimes on rap lyrics if you don’t want them used, or at least get out of my county.”

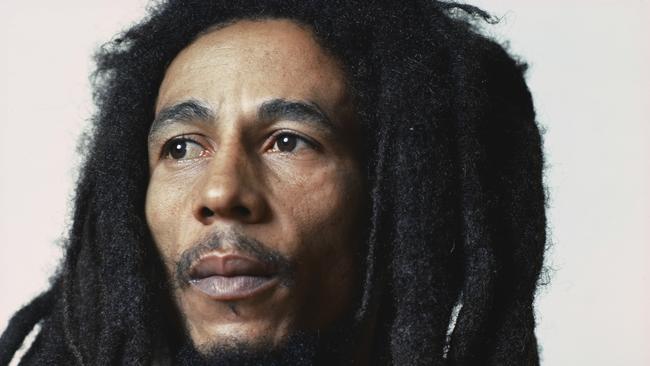

The history of pop music is full of violent content: Johnny Cash sang that he shot a man in Reno; Bob Marley and Eric Clapton both sang about shooting sheriffs. Yet lyrics are rarely used against musicians in non-rap genres such as country, whose song forms include the “murder ballad”, or songs about the events leading to a murder.

Rap has drawn legal controversy for decades. In 1990, members of the group 2 Live Crew were arrested for obscenity. Later that decade, gangsta-rap lyrics became a political issue on Capitol Hill; rappers became more of a financial risk for record labels, up-ending the music business even as the genre grew in commercial clout. The rap industry has largely won its battles against censorship.

More recently, industry executives and rappers including Kendrick Lamar opposed a short-lived move by Spotify to remove controversial artists like XXXTentacion from certain playlists. Just last week, Spotify CEO Daniel Ek said the music of Kanye West, whose string of recent anti-Semitic comments have elicited widespread condemnation, did not violate company standards. At the same time, musicians in the “drill” sub-genres of rap have come under pressure from some police for the hyperspecific taunts in their lyrics, which authorities claim fuel violence.

Rap lyrics, which can have violent, crime-related themes, are routinely used as evidence against amateur rappers in court, executives said. The practice has also affected well-known acts such as Snoop Dogg, Mac, Boosie Badazz and the late Drakeo the Ruler.

Music executives argue that by treating rap lyrics as de facto confessions or pure autobiography, prosecutors misunderstand how art works. In many cases, the legal strategy plays – especially for jurors and judges unfamiliar with rap – on stereotypes of criminality among Black people, injecting implicit racial bias into proceedings, according to Erik Nielson, professor of liberal arts at the University of Richmond and co-author of Rap On Trial: Race, Lyrics, and Guilt in America.

Nielson says he has counted roughly 500 instances of rap lyrics being used as evidence through 2017. But he says that’s almost certainly an underestimate, since his data is based only on available information from the small percentage of cases that went to trial. Meanwhile, non-rap lyrics have been used as evidence only a handful of times, he says.

With music executives applying more pressure on the issue, they’ve seen some traction with legislation on the state and federal level.

In September, California passed a law requiring courts to evaluate whether to include creative works like lyrics by weighing their value in the case against the risk of prejudicing proceedings. However, politicians have proposed stronger bills in New York and New Jersey that make it significantly harder for prosecutors to use lyrics, Nielson says.

The music industry coalition favours the New York proposal and a federal bill called the Restoring Artistic Protection Act. These bills presume the inadmissibility of lyrics and then set a number of bars prosecutors have to clear for inclusion, Nielson says.

The Wall Street Journal