Pushback on Xi’s vision for China spreads beyond US

Countries that once avoided upsetting Beijing are moving closer to Washington’s harder stance, placing curbs on China.

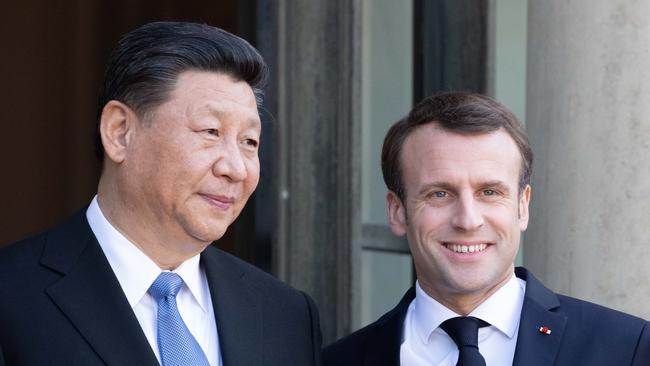

In March 2019, Xi Jinping flew to Paris to meet French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the then-president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker.

After toasting with flutes of Champagne, the Chinese president pressed the three leaders, according to an official present. A recent European Union policy paper had described China as a “systemic rival.” Did the Europeans really mean it?

Ms Merkel demurred with a compliment for Mr Xi, saying the language showed Europe recognised China’s growing strength and influence, the official said. Mr Juncker cut the tension with a joke about the EU’s inability to agree on what China was. But Mr Macron was blunt, the official recalled.

It’s true, the French president said. You are a rival.

A few weeks later, France sent a warship through the Taiwan Strait, provoking Beijing, which accused the frigate of illegally entering Chinese waters.

Inside China, Mr Xi’s authority is increasingly seen as absolute. He has sidelined rivals, silenced dissidents and bolstered his popularity by promoting a resurgent China unafraid to assert its interests.

The biggest challenge to his vision for China comes not from within its borders but from other parts of the world, in nations whose views of Beijing have dramatically changed in just a few years.

Countries that once avoided upsetting Beijing are moving closer to Washington’s harder and largely bipartisan stance — to curb Chinese access to customers, technology and sensitive infrastructure.

Australia, economically dependent on China, became one of the first countries to block Huawei Technology Co. on its soil, and led global calls for an investigation into China’s initial handling of the coronavirus. India, once a pillar of the world’s nonaligned movement, is expanding military cooperation with the US and its allies as it fights with China over contested borders.

Europe now trades roughly as much with China as America, and is on the brink of concluding an investment pact with Beijing that would further deepen those economic links. At the same time, the continent has installed new barriers to Chinese acquisitions and technology.

The UK and France have chipped away at Huawei’s ability to compete in Europe, and while Germany remains cautious, debates there about Europe’s dependency on China are growing more heated. This summer, after Beijing curtailed freedoms in Hong Kong, EU countries unanimously backed sanctions, a once unthinkable step.

Foreign leaders cite complaints about the way Mr Xi’s government initially handled Covid-19, its clampdowns on Muslim minorities in Xinjiang and democracy activists in Hong Kong and greater competition from Chinese companies that once were customers. China’s “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy, named after a nationalistic Chinese film franchise, has left many politicians and businesspeople feeling targeted.

“What happened during the last year ... is a massive disruption or reduction in support in Europe, and elsewhere in the world, about China, ” the EU’s ambassador in Beijing, Nicolas Chapuis, said at a Beijing energy forum earlier this month. “And I’m telling that to all my Chinese friends, you need to seriously look at it.” A Pew Research Center survey in October found distrust in Mr Xi reaching highs in nearly every country surveyed.

“China has become plank number one for the US in our diplomatic conversations with Europeans,” said former US Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs Wess Mitchell, who stepped down last year. “Our best ally in the effort to make China an issue is China’s own behaviour.” China has said that negative views toward Beijing are an issue mainly in Western countries, and have been stoked by Washington. One senior Foreign Ministry official said that many Chinese diplomats feel beholden to an increasingly self-confident population back home, and a leadership that wants to showcase China’s growing stature, even at the cost of antagonising officials abroad.

Chinese officials have highlighted how Beijing has contained Covid-19 and provided aid and investment across the world. In response to questions for this article, China’s foreign ministry said it sees Europe as a strategic partner, not a rival, and defended its own approach to international relations. “The body of China’s diplomacy is soft, but its bones are hard,” it said.

There are limits to opposition to Beijing. China’s economic might means most countries can’t afford to push too hard, and much of the world looks to Beijing to fund infrastructure or for access to a Covid-19 vaccine. America’s European allies have had their own disagreements with Washington and frequently sidestepped pressure from the Trump administration to coordinate China policy.

Germany’s Ms Merkel remains committed to engagement with Beijing, European officials said. She has been the main driver for the EU to complete an investment pact that would further bind Europe’s economy to China’s, and is pushing to cement a deal before a new US president takes office. Still, concern about China’s market power is growing in Germany, which has 5,200 companies active in China. And some EU lawmakers are threatening to block approval of the pact when it reaches them.

Earlier in Mr Xi’s tenure, most European leaders saw China mainly as an opportunity — a vast market whose rising stature could help balance out US dominance.

Since then, backlashes have built across the continent, especially in smaller countries such as the Czech Republic and Sweden, where heavy-handed actions by Chinese diplomats fueled resentment, and among business leaders who worry about unfair competition with Chinese companies.

Officials including Mr Juncker, when he was European Commission president, have worked behind the scenes to stiffen leaders’ spines. So, too, have diplomats from Australia, who have crisscrossed Europe connecting China critics in smaller nations with counterparts elsewhere in a little-known effort that has buttressed similar ones by Washington.

That has put more pressure on Europe’s bigger powers, including Germany, to stand up for the continent’s interests, even if it risks blowback from Beijing.

Concerns about Mr Xi already were building in 2018, a time of heightened tensions between the EU and the Trump administration that some thought might push Europe and China closer together.

In July of that year, Mr Juncker and other EU delegates met Mr Xi in Beijing, days after a fractious NATO summit between Mr Trump and European leaders when the US president suggested he could pull Washington out of the alliance. Mr Trump had shocked EU officials by saying in an interview the EU was among America’s biggest foes.

Mr Xi, by contrast, was welcoming the EU officials with a state dinner. He offered vague reassurances of opportunities for European businesses and collaboration on climate change, according to three people present.

As waiters cleared plates, his language shifted, those people recalled. China’s state-led model would flourish in a globalized era of free trade, Mr Xi said. Europe was hobbled by “its slowness of decision making,” and income inequality was fueling populism, he said, mentioning the Brexit referendum, a sore point for his guests.

Mr. Juncker fired back a retort, according to two officials present: “What you call slowness, we call democracy.” Mr Juncker left convinced that China was trying to use Europe in its fights with the US. He told aides the EU could do that, too, meaning use its talks with Beijing to gain leverage with Washington. Two weeks later, he met President Trump and signed a surprise EU-US trade truce. Mr Juncker has since retired and couldn’t be reached for comment.

Around that time, a group of German industry representatives and policy makers gathered at Castle Ziethen north of Berlin for a two-day discussion of China’s ambitions to compete with Germany in industries like robotics, autonomous driving and clean-energy vehicles. Chinese companies had acquired a string of strategic German assets, adding urgency.

The business leaders agreed to lobby for tougher policies on China. They produced a policy paper, circulated among top German and EU officials, warning that liberal market economies risked losing out to China, a country it labeled a “systemic competitor.” Australian officials, wary of China’s rise, noticed that language and repeated it during meetings with Germany’s foreign ministry. Australia had just blocked Huawei from installing 5G equipment at home, after which China penalised Australia’s barley and beef exports. Berlin was underestimating problems that came with economic dependency on China, the Australians argued.

Ms Merkel, however, wanted to expand engagement with China and, according to two European officials, privately floated a summit that would bring Mr Xi to Germany for a first-ever meeting with all EU national leaders in September 2020. Before then, she hoped, Beijing would afford European businesses more access to China’s market, allowing the investment pact to be signed at the meeting.

A spokesman for the German government said it doesn’t comment on confidential conversations and internal deliberations.

Elsewhere in Europe, though, complaints about China were spreading. In the Czech Republic, officials were taken aback when their cybersecurity agency determined that somebody acting in China’s interests had hacked the foreign ministry’s email and researched Czech positions on issues sensitive to Beijing, such as Tibet, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Although Huawei wasn’t implicated and China’s government denied any involvement, the agency decreed in late 2018 that government data could no longer be sent over the company’s hardware or software. Officials worried Chinese law could compel Huawei to cooperate with Chinese intelligence gathering. Huawei has denied it would surrender data to Beijing.

China’s ambassador, Zhang Jianmin, a former interpreter for Mr Xi, came to the foreign ministry and issued a warning, according to people familiar with the matter: If the Czech Republic didn’t retract its position on Huawei, Chinese tourists would stop coming, and other economic consequences would follow.

Prague, inundated with tourists, was eager to thin the crowds. Instead of backing down, Czech officials worked with the White House National Security Council to bring European officials to Prague for an internet-security summit. Chinese representatives weren’t invited.

Some French, German and Dutch officials worried the summit would needlessly offend China, but they came anyway, according to several participants. Australians at the event warned: Today Beijing is punishing us, but tomorrow it will do the same to you. The Germans attending took notes.

An EU policy paper early last year called China not just a partner and competitor but a “systemic rival.” The language startled China’s diplomats to the EU, according to one of them familiar with their response.

The Chinese diplomats looked up “rival” in a dictionary to better understand all its connotations, then asked, in a formal request for explanation: By rival, did the EU mean enemy?

Mr Xi had the same question when he arrived in Paris in March 2019 for a meeting with Mr. Macron. The French president had his own beefs with China, including in Africa, where Paris competes with Beijing for influence. Mr Macron asked Mr Juncker and Ms Merkel to join the meeting.

Mr Xi grew visibly unhappy when the topic of “systemic rival” came up, said an official who attended. To lighten the mood, the official said, Mr Juncker cracked a joke about how his native Luxembourg had never declared war on China because it was too small to house all the prisoners it would take.

After a few more weeks of talks with EU officials, Mr Xi’s government offered to commit to provide broader EU access to Chinese markets. European firms would in principle be able to trade and invest in China just as Chinese companies did in Europe.

But as months rolled by, talks to fulfill that promise stalled. Instead of easing the flow of trade, Beijing threatened new restrictions to punish European actions it said offended China’s people.

In Sweden, after a cabinet minister awarded a literary prize to a jailed Swedish-Chinese dissident bookseller, China’s ambassador warned of economic consequences. “For our enemies, we got shotguns,” he told a Swedish reporter.

In the Czech Republic, Beijing called off a China trip by the Prague municipal orchestra, citing a quarrel with the town’s mayor over the status of Taiwan. The rebuke was also retaliation for the Czech warning against Huawei, the ambassador later told Czech diplomats.

The Chinese ambassador then delivered a written warning to a 72-year-old Czech senator planning a trip to Taiwan: If relations didn’t improve, there would be consequences for one of the few Czech companies exporting to China, piano maker Petrof s.r.o.

Days later, the senator died of a heart attack. A sale of 11 pianos to a Chinese buyer fell through.

A Czech billionaire purchased the unsold pianos, and 90 Czech politicians, businesspeople and academics flew to Taiwan. When the Chinese ambassador phoned to complain, one Czech official set down her phone on the desk, ignoring him while he spoke, the official recalled.

China’s Foreign Ministry, in its response to questions, expressed “grave concern and strong dissatisfaction” at the recent behavior of Czech officials and groups that have “caused disturbances involving China’s core interests.” By late spring, other governments were joining the chorus. As demonstrations continued in Hong Kong, a former British colony, the U.K. started nudging its former EU partners toward a firmer stance, circulating a 12-point memo on China’s plans. Mr Xi was breaching the 1984 Sino-U.K. agreement that returned Hong Kong to China with certain freedoms enshrined, U.K. officials argued.

In late July, the EU approved sanctions that included ending extraditions to and from Hong Kong. The U.K. barred its telecom companies from buying Huawei equipment, after earlier saying it could manage any security risks.

Ms Merkel was looking more isolated. Her EU-China conference, slated for Leipzig in September, had been downgraded because of coronavirus to a video call between Mr Xi, Ms Merkel and two top EU officials.

The main topic was supposed to be trade, but one hour in, Charles Michel, one of the EU’s top two officials, pressed China on human rights. Mr Xi started rattling off statistics, noting a 10% increase in anti-Semitic incidents in Germany. He also alluded to the Black Lives Matter movement spreading from America, and mentioned migrants drowning at sea, according to two officials on the call.

“We don’t take any lectures,” China’s president told them, according to attendees and China’s state news service. “Nobody has a perfect record.” Mr Michel responded that the EU at least had policies to resolve human-rights problems. “We are far from perfect,” the two officials on the call recall Ms Merkel saying, “but we are willing to address probing questions.” By the call’s end, neither side had progressed much on trade. Weeks later, the EU’s top diplomat held a call with US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to settle on a shared goal: The US and Europe should coordinate on China. That cooperation is set to intensify once President-elect Joe Biden takes office, the diplomat recently said.

Rachel Pannett contributed to this article.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout