Prince Harry’s pagan progress

Spiritual but ‘not religious’, he seeks enlightenment like a typical millennial: via drugs and meditation - a far cry from his ‘committed Anglican Christian’ upbringing.

Prince Harry’s memoir, “Spare,” is among other things a spiritual autobiography—a New Age story of suffering and rebirth. Harry has said he’s “not religious,” but he is spiritual. Christianity leaves him cold, but he pursues enlightenment with a zeal that would have warmed the heart of a Puritan divine. He travels this path alone, guided by drugs, spirit animals sent by his late mother, Diana, and daily yoga and meditation.

Harry’s father, King Charles III, may be supreme governor of the Church of England, but when it comes to the inner life, Harry, who was born in 1984, is a typical millennial. Pew Research reported in 2010 that Americans 18 to 29 were “considerably less religious than older Americans.” Twenty-six per cent of Millennials said they had no religious affiliation, and they were also less likely to pray every day than members of Generation X (41% vs. 54%). Yet the percentage of Millennials claiming “absolute certainty” in God’s existence (53%) wasn’t far off the figures for baby boomers (59%) and Generation X (55%) when they were young.

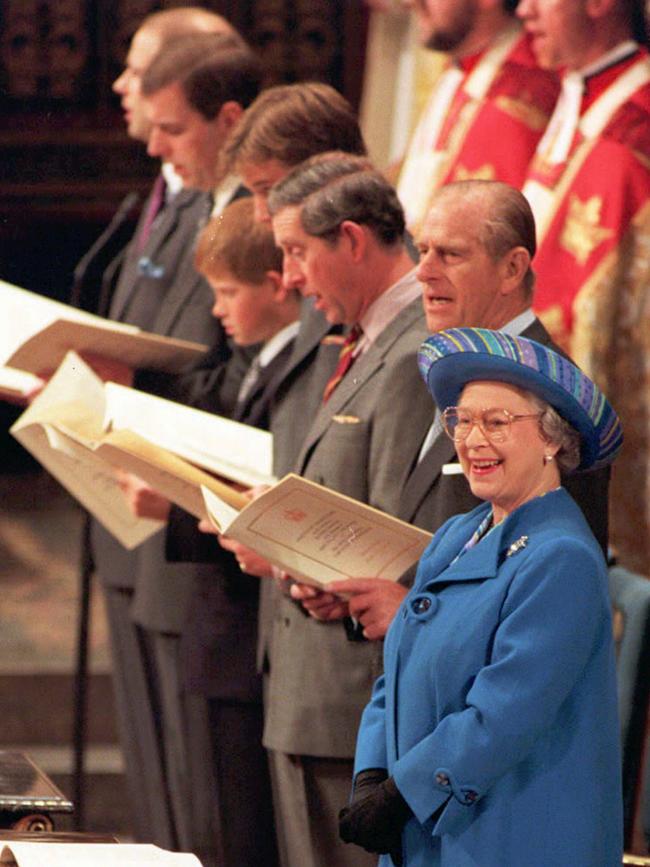

For Harry’s grandmother Elizabeth II, personal faith was indistinguishable from her constitutional duty. King Charles describes himself as a “committed Anglican Christian,” and Harry says he set a “deeply religious” example and “prayed every night.” Harry attended church regularly as a child, obligatory given the Windsor family’s alliance with the church.

Harry was 12 when his mother died in a car crash in Paris. The Christian rites at her funeral in Westminster Abbey couldn’t console him. His only regular contact with the Bible came when a teacher, punishing teenage misdemeanours, delivered “a tremendous clout, always with a copy of the New English Bible.” This, Harry writes, “made me feel bad about myself, bad about the teacher, and bad about the Bible.”

At around 15, Harry experienced a ritual induction into manhood. Guided by Sandy, a family retainer, he shot a stag. Sandy slit the dying animal’s throat and belly and told Harry to kneel. “I thought we were going to pray,” the prince writes. Instead, Sandy pushed Harry’s head inside the carcass and held it there. “After a minute I couldn’t smell anything, because I couldn’t breathe. My nose and mouth were full of blood, guts, and a deep, upsetting warmth.”

“So this,” Harry tells himself, “is death.” Yet he’s ecstatic. “I wasn’t religious,” Harry writes, “but this ‘blood facial’ was, to me, baptismal.” Finally, he has lived the “virtues” that had been “preached” to him since childhood. Culling the herd is being “good to Nature” and “good to the community.” Managing nature is “a form of worship,” and environmentalism is “a kind of religion” for his father. For the first time Harry feels “close to God.”

This pagan rebirth carries strong symbolic overtones for Harry. Monarchy is a survival from the earliest times. So is the hunt, with its symbolic echoes of religion’s roots in animal sacrifice and seasonal rites. The Windsors live in urban captivity, but their spiritual home is the Scottish Highlands, where the stag is the monarch of the glen. Diana shared her name with the Greek goddess of the hunt—and Harry writes that she was “hunted” to her death, the cameras still “shooting, shooting, shooting” as she lay trapped in the wreckage.

Homer relates that when Agamemnon is on his way to the Trojan War, he offends Artemis (whose Roman name was Diana) by killing one of the goddess’s sacred stags. Harry too goes to war. Military service gives him purpose, but the Taliban reads the papers. When an Australian tabloid publishes Harry’s location, he is extracted from Afghanistan in a hurry. More drinking and drug use ensue. Lost in grief, Harry is a pilgrim in a world of sorrow. Christianity is a language of dead metaphors. Childhood vacations in St. Tropez are “heaven,” but hell is palpable as Sartre’s torment: other people, especially when they want to take Harry’s photograph.

Therapy and self-medication with psychedelics make life bearable but only love can return Harry to life. Encouraged by his new girlfriend, Meghan Markle, he takes up yoga, visits a medium, and stops eating takeout. Meghan prostrates herself on Diana’s grave, praying for “clarity and guidance.” When a hummingbird flies into their new family’s home in Montecito, Calif., it is an “Odysseus,” confirming the end of the hero’s journey. The Spanish, Harry says, call the hummingbird the “resurrection bird.”

Harry’s narrative of resurrection bears formal resemblance to the Gospels, but its content owes more to Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell and the Californian gospel of self-care. His neopagan progress is that of many Millennials—especially those who, like Harry, are white men with no college education. By 2017, Pew found that 38% of Americans 30 to 49 were “spiritual but not religious.” Sixty-seven per cent of the unchurched were “absolutely certain” of God’s existence, and 24% “fairly certain.” Fifty-seven per cent prayed “at least daily,” but 76% “never” participated in group study or prayer. Like Harry, they are solitary and syncretic, inward travellers with no direction home.

Mr. Green is a Journal contributor. His latest book is “The Religious Revolution: The Birth of Modern Spirituality, 1848-1898.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout