Police snipers and drone patrols: the new reality for US election workers

A top Republican election official said ‘you’d have to be a psychopath to enjoy this’ as the reality of the 2024 election in battleground states takes hold.

As November 5 looms, the election headquarters in the most populous county in the crucial battleground state of Arizona has become a fortress.

“You’d have to be a psychopath to say you enjoy this,” said Maricopa County’s top election official for voting by mail, Stephen Richer, a Republican. The building has added metal detectors and armed guards. On Election Day, as workers tabulate ballots behind new fencing and concrete barriers, drones will patrol the skies overhead, police snipers will perch on rooftops and mounted patrols will stand ready.

Across the state, election workers have gone through active-shooter drills and learned to barricade themselves or wield fire hoses to repel armed mobs. At the ready are trauma kits containing tourniquets and bandages designed to pack chest wounds and stanch serious bleeding.

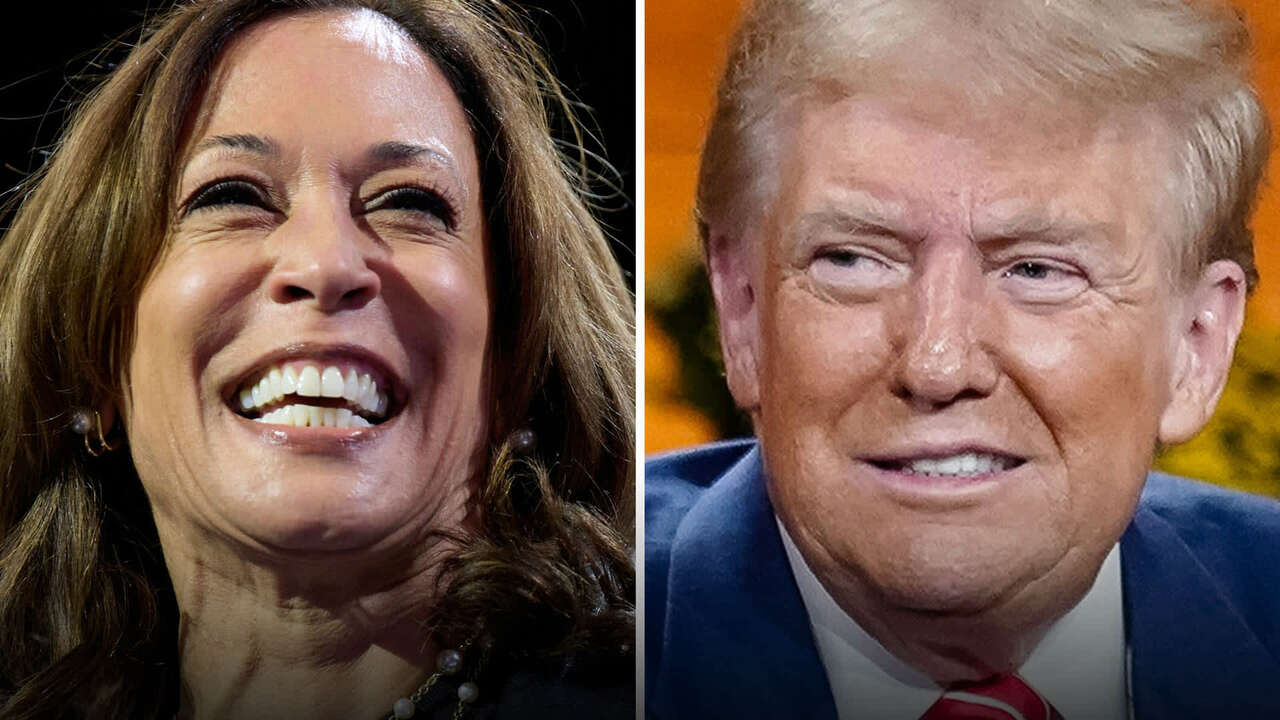

Arizona is one epicenter for threats against election officials propelled by years of Donald Trump’s false claims that the 2020 election was stolen, which he has told his supporters could happen again. Richer and his colleagues have endured intimidation and death threats for not heeding the call by Trump and others to reject the 2020 results. Some have been provided with added security protection.

Four years of baseless allegations of election fraud have created an atmosphere of fear and intimidation among election officials from Atlanta to rural Washington state, transforming the way workers in many parts of the country are approaching the most fundamental of civic duties.

“To be honest, it was easy in the beginning to say that it was just a 2020 thing -- it’s done, it’s over,” said Justin Smith, a retired Colorado sheriff who has been training law enforcement and election officials to prepare for Nov. 5 in dozens of states. “Well, since then we’ve proven that it’s a trend that’s moving forward.” In Colorado, death threats from election deniers have led some county clerks and election officials to have bulletproof vests on hand. Nationwide, many election offices are stockpiling Narcan, a drug used to reverse opioid overdose, after some received ballot envelopes last November containing white powder with traces of fentanyl.

“I’ve spent my nights awake, thinking of every worst case scenario that could happen,” said Tonya Wichman, director of the board of elections in Defiance, a county of 38,000 in northwestern Ohio. In that county, she said, every polling location will have a radio to keep in constant communication with law enforcement on Election Day. Police and sheriff’s deputies will check in on polling sites every half-hour, she said, “to make sure they’re OK.” Election officials worry that even inadvertent human error or routine actions by election workers on Nov. 5 might be misinterpreted and spread rapidly through a misinformation ecosystem that has grown more pervasive since 2020.

These days, a video of a poll worker crumpling up a piece of paper can quickly escalate, said Chris Harvey, who was Georgia’s elections director from 2015 to 2021. This year, Georgia became the first state to require election-law training for police, and Harvey is leading it.

“People have had four years of just marinating in all sorts of different conspiracy theories, and we worry they’ll come in looking for a problem, ” he said. “Then you got, ‘Hey everyone come down to the polling place,’ and mobs showing up, maybe armed, and it can really snowball very quickly.” What transpires on Nov. 5 might determine whether this year’s militarization becomes the new norm, a prospect that unnerves officials who say it not only strains resources but risks undermining a rite of democracy.

In some places, churches and schools that have long served as polling sites have opted out this year over security concerns, officials said. The fear has spread to poll workers, many unpaid and often elderly volunteers.

“I’ll be really honest, I’m scared,” one person posted on a local forum discussing whether to sign up as a poll worker in Virginia. “Y’all saw what they did to those poor women in Georgia” the poster said, referring to volunteers who were threatened by election deniers in 2020 after false claims that they changed votes went viral.

Arizona’s Maricopa County, with nearly five million residents, is one of the nation’s largest voting jurisdictions. Richer and his staff are hoping the new security protocols will help ensure a smooth election.

“We’ve had to change procedures to make sure temporary [poll] workers feel safe, which hasn’t happened before,” said Richer’s executive assistant, Joshua Heywood. “Nobody 10 years ago was taking pictures of temporary workers and their license plates as they were leaving the building.” “It feels very dystopian,” said Richer.

‘We’re going to hang you’ Richer, 39 years old and Maricopa County’s recorder, is an unlikely target of political controversy. A hip-hop enthusiast and former improv comedian, he won his first elected office in 2020 with a folksy platform: “Make the Recorder’s Office Boring Again,” succeeding a Democrat.

Trump’s narrow defeat in Arizona obliterated that plan. Trump and his supporters alleged vote rigging in Maricopa County and pushed for an inquiry, hoping to prompt similar reviews in other states. The subsequent audit ordered by the GOP-led state Senate audit confirmed the November results, reaffirming Biden’s win in the county and the state.

Nationwide, the Trump campaign and its allies lost dozens of lawsuits challenging the 2020 results, and the Justice Department found no evidence of fraud on a scale that could have affected the presidential outcome. A bipartisan consortium of local, state and federal election officials declared the 2020 race the most secure U.S. election in history.

Nevertheless, Trump has continued to assert the election was rigged, and the Republican Maricopa County officials that upheld the election results became lightning rods. Bill Gates, a Republican member of the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors that oversees in-person voting, said he has been diagnosed with PTSD from threats he received for defending the results, and has lost friendships.

“We understand politics is a blood sport, but you don’t expect it from people in your own party,” said Gates, who isn’t seeking re-election after eight years, partly because of harassment.

The Justice Department has charged three individuals for threats against Richer, including a Missouri man who allegedly called his cellphone and warned, “You need to do your f -- job right” or “your ass will never make it to your next little board meeting.” Other threats against Maricopa officials, detailed in court filings, include menacing messages such as, “You’re going to die, you piece of s -- . We’re going to hang you. We’re going to hang you.” A Texas man accused of suggesting “a mass shooting for poll workers” and posting threats about Richer and Tom Liddy, a chief in Maricopa County Attorney’s Office, was sentenced to 3 1/2 years in prison by a Trump-appointed judge in 2023.

Frederick Francis Goltz admitted to posting Liddy’s name, purported home address and phone number on the far-right site Patriots.win and writing, “It would be a shame if someone got to this [sic] children.” Liddy’s kids were provided with body armor, and armed guards surrounded his house. Liddy, a Republican, evacuated his office during a bomb threat while working on an appellate brief defending the 2020 election.

“Of course, I was able to finish the brief...because I will not be intimidated,” Liddy said in court. “Not ever. I will not be intimidated.’ Richer said threats caused 10 longtime members of his 140-person permanent staff to resign for safety reasons. An untold number of 3,000 temporary workers, he said, also were scared off, some after angry Trump supporters surrounded their cars, took photos and berated them as they left the downtown election center.

“I had one lady break down in tears,” Richer recalled. “She signed up for just a job where she thought she could help her community, and she didn’t sign up for this.” “The threats and harassment that these employees face are both alarming and pervasive,” wrote Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Scott Blaney, who was appointed by a Republican governor, when ruling in August that the Maricopa County recorder’s office needn’t publicly disclose names of low-level election workers, as requested by a political-action committee called We the People Arizona Alliance. Blaney cited a 30-year Maricopa County employee who received some 50 threats and harassing messages accusing her of “stealing the 2020 election,” and who “routinely needed to be escorted to her vehicle after work.” Election officials worry there will be more such incidents this cycle, as some Americans seek evidence that officials are trying to alter election outcomes. The singling out of usually anonymous election administrators and poll workers marks a significant change, said Amy Cohen, executive director of the National Association of State Election Directors. Previously, flare-ups were largely isolated and driven by anger at policies or current events, she said. “The shift has been really stark,” she said.

Nationally, nearly 40% of local election officials reported experiencing threats, harassment or abuse due to their jobs, according to a survey released in May by the Brennan Center, a nonprofit voter rights group. Death threats and other forms of intimidation, including suspicious packages and bomb threats, have risen “meteorically” since 2020, the group reported.

Last November, election offices in five states received suspicious letters, some later found to contain fentanyl. One read “End elections now.” Officials in 20 states received another round of suspicious packages last month, including one claiming to be from the “United States Traitor Elimination Army.”

‘It’s a civil war’

In Arizona, Richer’s critics include Republican Shelby Busch, co-founder of We the People AZ Alliance, which was launched in late 2020 and has taken in nearly $1 million, including from Mike Lindell, the MyPillow chief executive known for spreading stolen-election claims. The group sells mugs, tumblers, hoodies and other merchandise.

Busch, who was named volunteer of the year by the Maricopa County Republican Committee in January, made headlines in June when a video surfaced of her saying in an address at a GOP event: “If Stephen Richer were in this room, I would lynch him.” “This isn’t healthy,” Richer responded on X. “And it’s not responsible. And we shouldn’t want it as part of the Republican Party.

“I didn’t mean it literally,” said Busch in an interview with The Wall Street Journal. “It was hyperbole and meant in terms of political lynching...the point was to end his career.” Busch repeated unfounded conspiracy theories of fraudulent ballots infiltrating the system. “I mean, look, chain of custody, right?” she said from a county GOP office with a Trump cardboard cutout in the lobby.

Richer finds it ironic to be a target of such ire, as a lifelong conservative who voted for Trump in 2020. He attributes it to not supporting Trump’s assertion he won Arizona. “You have to be 100% loyal, ” Richer said. “If you ever show any doubt, then they come for you.” Other Republicans who didn’t support Trump’s election-theft claim have been ostracized, too. “It’s a civil war,” said State Sen. Ken Bennett, a Republican who lost his primary challenge to an election denier, despite twice voting for Trump.

Richer lost his GOP primary in July, and his term as county recorder ends in January. During campaign visits to Republican groups, he was booed when he refused to say Trump won in 2020. “Stephen was a victim of it. I was a victim of it. They just believe entirely the four or five words out of his mouth that the election was stolen,” Bennett said, referring to Trump.

At a voter mobilization rally for Trump in north Phoenix on Oct. 8, supporters who contend Trump was robbed in 2020 talked about how to prevent a recurrence. “There’s no cavalry coming -- we are the cavalry,” Abraham Hemenedh, a candidate for a congressional seat, told the roomful of Republicans in a strip mall that also houses a snake store.

Attendee Bryan Sheets, 60, said he intends to follow advice from the Trump campaign to vote early, despite his distrust of mail-in ballots. Sheets said he is worried about whether his vote will be counted. “I wish they could respond back to you and let you know who your votes were for,” he said.

Richer said such concerns are unwarranted because of the election system’s many checks and balances. Millions in security upgrades have been made by Maricopa County since 2020. Those include two trailers of computers behind the election center to help verify voter signatures on ballots.

The central clearinghouse for all ballots, called the Maricopa County Tabulation and Election Center, is now protected by a 7-foot-high wrought iron fence, concrete barriers and armed officers at every door. Inside, cameras are aimed at ballot holding areas secured by metal fencing. A 24-hour live feed is available to the public. “It feels like we’re in a nature show,” said Taylor Kinnerup, a spokeswoman for Richer’s office.

Richer and other election officials have expanded public tours and visibility to try to pre-empt election conspiracies. “When people don’t know what a process is or understand it, it’s real easy to create narratives in their own minds,” said Dana Lewis, the recorder in Pinal County, Ariz, where a new $32 million voting center features bullet-resistant glass, bollards to thwart vehicles, gates around the periphery, and security cameras monitoring the entire building. Her staff is inviting both poll watchers and the general public to observe the process.

Runbeck Election Services, which prints ballots for Arizona and 29 other states in a building near the Phoenix airport, has conducted “north of 100” tours so far this year, said CEO Jeff Ellington. “We want to be apolitical,” he said.

Busch, the election skeptic, said the new cameras don’t allay her concerns. “The way they put the angle of the cameras,” she said, “you can’t see anything of value.” The Maricopa County Republican Committee, whose top two officials say the 2020 election was rigged, plans to deploy far more poll workers and observers than in previous elections, and GOP workers will monitor live feeds from the elections department.

With less than three months before his term ends, Richer isn’t departing quietly. “I haven’t stopped showing up to the office,” he said, “and this hasn’t stopped being important to me.” He added: “We’re going to go through the wringer again.”

The Wall Street Journal