Pandemic Fatigue Is Real – And It’s Spreading

Collective exhaustion with coronavirus restrictions has emerged as a formidable adversary for governments.

From the corridors of Washington to the cobblestones of Paris, the coronavirus is roaring back and authorities are ramping up restrictions again. This time around, however, everyone is tired.

Hospital staff world-wide are demoralized after seven months of virus-fighting triage. The wartime rhetoric that world leaders initially used to rally support is gone. Family members who willingly sealed themselves off during spring lockdowns are suddenly finding it hard to resist the urge to reunite.

Zoe Sharp, a 43-year-old human-resources leader in Washington, D.C., has been stringent with her family throughout the pandemic, sanitizing elevator buttons, airing out packages and microwaving the newspaper. Her 4-year-old son Hank even created a no-cuddle list to protect family members who are more vulnerable to the virus, like his grandparents.

A week ago, however, something snapped. Ms. Sharp booked a trip to visit her father-in-law in Memphis, Tenn., replete with a stop at the local theme park. Grandpa is now off the no-hug list.

“I need something to look forward to,” Ms. Sharp says, adding that her children “want to see their grandfather. They’re worried about him, and they talk about him a lot.” The collective exhaustion — known as pandemic fatigue — has emerged as a formidable adversary for governments that are counting on a high degree of public cooperation with the latest rounds of restrictions to flatten the infection curve. Too much pandemic fatigue, authorities say, can fuel a vicious cycle: A tired public tends to let its guard down, triggering more infections and restrictions that in turn compound the fatigue.

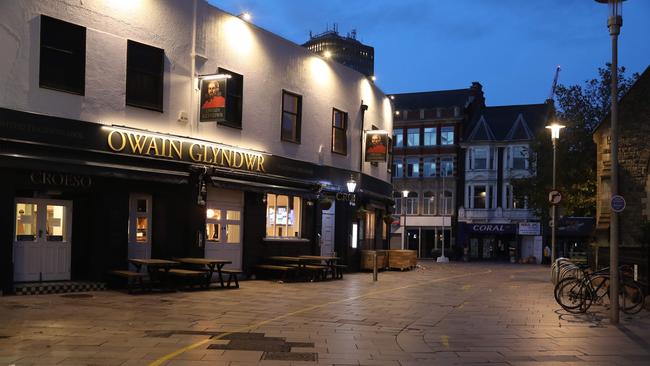

That is part of what is driving the recent spate of policy reversals. Bars and cafes that reopened after the spring lockdown are suddenly off limits again. Workers who were told to return to their offices are now being asked to work from home if possible. In France, authorities recently halved the length of quarantines to one week, believing it would boost compliance.

“It’s a matter of balance. To be able to enforce a new rule, we need to make sure first that people can accept it,” French Education Minister Jean-Michel Blanquer said in an interview.

Surveys on both sides of the Atlantic show people are better at keeping up with the latest rules and advice when it comes to personal hygiene, like hand-washing and masks. Weekly Gallup polls of between 2,714 and 9,353 people in the U.S. found that 91% of respondents said they had worn a mask in the past seven days as of Sept. 27, compared with 80% as of May 10.

Problems begin when the rules run up against the need for social connection. Gallup polling over the same May-to-September period showed the number of Americans avoiding small gatherings with family and friends had fallen from 71% to 45%.

A government survey in France found that 72% of people said they were avoiding gatherings and face-to-face meetings as of mid-May, right after the country’s lockdown ended. By Sept. 23, that figure had fallen to 32%. In the same time frame, the percentage who said they greeted others without shaking hands or embracing fell from 88% to 69%.

The resolve to wear masks also appears to weaken in certain social settings. A U.K. survey found that 98% of people reported wearing a mask over a seven-day period ended Oct. 11. That figure dropped to 19%, however, when it involved one-on-one social activity.

That is a problem, epidemiologists say, as winter sets in. More people will socialize indoors, where the virus spreads most efficiently, and at close quarters.

Younger people, wary of becoming vectors of infection, are walking a tightrope before they head home for the holidays.

Clémence Jujo, a 33-year-old human-resources worker, plans to travel to Lyon in November to attend a family reunion, an event that will bring her into contact with her parents and grandparents. The last time they were together, in June, shortly after France’s lockdown ended, Ms. Jujo said her grandmother told her she would rather die of Covid-19 than be deprived of contact.

Back in June, however, Ms. Jujo didn’t have to worry about infecting anyone, because she was among the millions of French who had freshly emerged from one of the West’s strictest lockdowns. Since then, Ms. Jujo has been navigating a busy social life and career in Paris, which has once again become one of Europe’s biggest hot spots.

She is back working in the office, where she wears a mask all day, even at her desk. When President Emmanuel Macron announced a 9 p.m. curfew, Ms. Jujo asked her boss if she could leave the office earlier than usual so she could squeeze in walks and time with friends. On a recent evening, she was sitting at an outdoor cafe table with her boyfriend. It was dusk, and the couple was trying to adapt their schedules to meet the curfew.

“It’s a lot of stuff, and it’s really exhausting,” she said. Vincent Henry, her 26-year-old boyfriend, is also tired. His business, selling wines and spirits, shriveled after the city’s restaurants, bars and trade fairs closed their doors. He hasn’t hosted a tasting since March. Instead he is living at home with his parents, whom he can no longer greet with the traditional kiss on the cheek.

“I have two master degrees, and I find myself making bicycle deliveries. That’s something I could have done at age 16,” he says.

When the lockdown hit London in March, the Diamond family went all-in. They set up a home office, bought a spin bike and limited their outings to a weekly stop at a grocery store where social distancing was strictly enforced.

They kept up the routine for seven months — even after the U.K. eased restrictions over the summer, allowing people to go back to restaurants, pubs and the gym. “We were really conscientious about it,” says 36-year-old Lawrence Diamond.

On Oct. 10, they decided it was time to socialize again. They met friends in a pub and invited people over for Sunday lunch.

“We were feeling much more confident, the virus seemed under control and it didn’t feel like we were putting anyone at risk by meeting up,” says Megan Diamond, his 35-year-old wife.

A few days later, Londoners were banned from having other people in their homes or going to the pub with people outside their household.

“Winter is long in Britain,” Mr. Diamond says. “No one’s not bored of this.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout