Pakistan begins deporting Afghan who fled the Taliban

The deportation drive comes as relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan have frayed.

Pakistan started rounding up tens of thousands of undocumented Afghans for deportation back to the country they fled, prompting fears that some awaiting resettlement to the U.S. could be swept up.

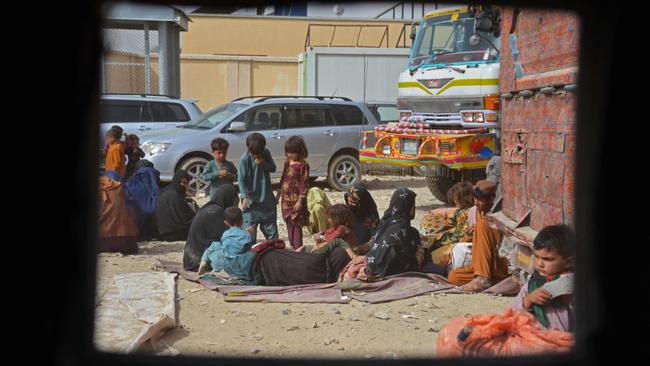

Police raids took place across the country on Wednesday, the deadline for undocumented Afghans to leave. “By midnight tonight return to your homeland,” warned a police officer speaking into a mic in one neighbourhood in the port city of Karachi, television footage showed. Mosque loudspeakers repeated similar messages across the country.

The deportation drive marks an about-face for Pakistan, which has for decades hosted millions of Afghans fleeing war and poverty. The repatriation comes after increasing attacks by Pakistani militants that Islamabad says are being harboured by the Taliban in Afghanistan since it took power in August 2021, following the U.S. withdrawal.

Pakistan denies any link between the deportations and its enmity with the Taliban and says that it is cracking down on illegal immigration, as many Western nations do.

“This is purely an administrative and legal matter,” said a senior Pakistani official. “This isn’t about refugees, it is only about those illegally resident here.”

An estimated 1.3 million undocumented Afghans live in Pakistan, almost half of whom crossed the border after the Taliban took over, arriving as Pakistan spiralled into an economic crisis. Islamabad says it can no longer support this population.

At least 120,000 people have returned to Afghanistan since the repatriation drive was announced in September, fearing arrest, according to United Nations agencies. Local television reports showed a tide of people on the move with their few belongings packed on trucks and push carts. This week, Afghans, including women and children, were loaded into police vehicles, according to witnesses and television footage.

In Rawalpindi, the northern city adjacent to the capital, a family of applicants for resettlement in the U.S. said six of them were detained Wednesday, and then released a day later, after showing their documentation. Police in Rawalpindi said that 600 Afghans were picked up Wednesday and any with valid paperwork were let go. Some applicants for U.S. resettlement said they had gone into hiding.

Sarfraz Bugti, Pakistan’s interior minister, has repeatedly said that the expulsion of undocumented Afghans is only the first stage of the drive, with documented Afghans and those awaiting relocation to the West to be repatriated at a later point. There are around two million Afghans with refugee or other registered status in the country.

“They must go back because their country is now peaceful, no war is going on,” Bugti said last week.

There are 25,000 Afghans in Pakistan who fled the Taliban takeover who are eligible for resettlement in the U.S., Washington says. These include those who worked with the American military, the former U.S.-backed Kabul government or in professions placing them at risk, such as journalism.

Islamabad and rights groups say that the processing of these people is taking too long.

Habibullah Aziz, a 33-year-old journalist who worked with an Afghan news channel and is awaiting relocation to the U.S., said that he came to Pakistan in January this year after receiving threats from the Taliban.

“Every minute I am in fear of being deported to Afghanistan, the situation is very dangerous for Afghans with or without documents,” said Aziz.

Western countries, including the U.S., have privately urged Islamabad to slow down its plans, to avoid deporting people waiting for resettlement, according to Pakistani and foreign officials.

Hundreds of soldiers, police and other officials from the former U.S.-backed government in Afghanistan have suffered reprisals since the Taliban took over, according to the United Nations. The Taliban denies the allegations.

“Helping facilitate the safe and efficient resettlement and relocation of eligible Afghans to the U.S. is a priority for the U.S.,” said a senior U.S. official. “The U.S. is engaged in intensive diplomacy with the Government of Pakistan to ensure that vulnerable individuals are not placed in harm’s way.”

The senior Pakistani official said that a list of 25,000 people in the U.S. visa pipeline was only shared by Washington on Oct. 31. He said the list provided inadequate information to identify people, for instance lacking photographs or addresses which could be used to protect them from repatriation.

There was no immediate comment from Washington on the detention of some of its visa applicants.

Shawn VanDiver, a U.S. Navy veteran who is the founder of the Afghan Evac Coalition, which campaigns to get at-risk Afghans to the U.S., said that the U.S. processing rate had soared over the past two years and that it is now Pakistan’s bureaucracy that is moving slowly.

“Pakistan isn’t being a good partner,” said VanDiver, who added that 50,000 Afghans have made it to the U.S. since the Taliban takeover, out of an estimated 300,000 eligible, in Afghanistan or waiting in other nations.

The Pakistani official said the U.S. has requested two more years to process these types of applications.

“We don’t have endless patience. We want this to be expedited,” said the official. “This isn’t adversarial. Our relationship with the U.S. is important.”

Even before the repatriation drive, monthly arrests of Afghans in Pakistan had surged 10-fold between January and October this year, the U.N. has said. Human Rights Watch, the U.S.-based campaigning group, said that Pakistan is using threats, abuse and detention to coerce Afghan asylum seekers. Pakistan says no human rights abuses are taking place as a result of the deportation campaign.

The Taliban says it will not allow Afghan soil to be used by armed groups to attack other countries. But they see the Pakistani militants as fellow jihadists, experts say. That has shredded the previously close ties between Pakistan and the Taliban that existed when the group was fighting the U.S.

The Taliban has criticised the expulsions and promised to help those returning. “We assure those Afghans who have gone to foreign countries due to some concerns that they can return and live a dignified life in their country, ” said the Taliban’s leader, Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada, in a decree last week.

But the Taliban administration has few resources, with millions in the country facing starvation. Returning also means that daughters will lose out as the Taliban bans females’ access to high school, university and many lines of employment.

Mujtaba Masoomy Asrar, a 27-year-old former university teacher in Kabul, came to Pakistan at the start of this year, afraid that his past criticism of the Taliban placed him at risk. He put his $US15,000 savings into setting up a shop, which employs Pakistanis.

“We could have invested in our own country, but we invested in Pakistan as our lives were at risk there,” said Asrar.

Pakistan has warned landlords and businesses that they could face prosecution for hosting or working with undocumented Afghans.

One Afghan who said he worked inside the U.S. Embassy in Kabul as a contractor and is part of the U.S. resettlement program said that he was evicted in October from his house in Rawalpindi, due to his landlord’s fears about repercussions from the authorities. The man, a 34-year-old with four young children, is now living in a guesthouse with his family.

“We might be killed, imprisoned or tortured if the Pakistan government deports us,” he said.

Esmatullah Kohsar contributed to this article.

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout