Microsoft hits back at the hackers

Microsoft’s new security chief, Charlie Bell, has a message for companies and institutions buffeted by cyberattacks: take shelter in the cloud.

Microsoft’s new security chief, Charlie Bell, has a message for companies and institutions buffeted by a seemingly never-ending string of cyberattacks: take shelter in the cloud.

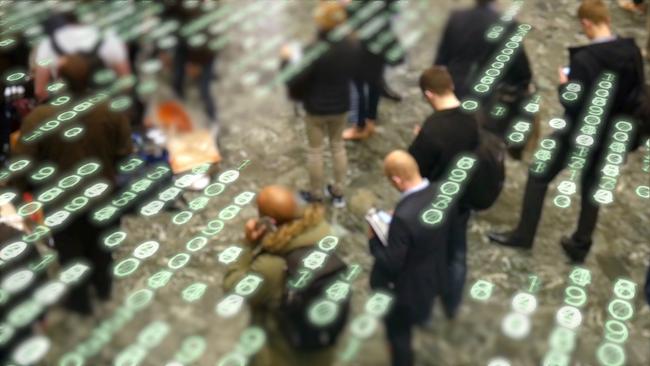

Microsoft has built a $US15bn ($20.8bn) business – and one of the world’s biggest private cyber armies – to counter cyberattacks, but the threats are expanding.

US banks flagged nearly $US600m in ransomware payments during the first six months of 2021, and cybersecurity experts put the cost of that much higher. Corporate and public networks are also under siege from scammers looking to steal money and government-backed hackers looking to steal their secrets.

“It’s sort of like the mother of all problems,” said Bell in his first interview since joining Microsoft from Amazon.com last year.

“If you don’t solve it, all the other technology stuff just doesn’t happen.”

Microsoft finds itself uniquely positioned in the centre of all of this activity, Bell says. Its email and office-productivity products are dominant on corporate and government networks, and it is the country’s No.2 provider of cloud-computing services.

Bell, who at Amazon helped build the world’s largest cloud business, says Microsoft is taking centre stage in combating cybercrime. Some of its customers have said the company has more to do.

Microsoft has been hit by a series of high-profile cyber intrusions in recent years. In December 2020, the company said it had been compromised by the hackers behind the cyberattack on SolarWinds – a group that US officials have linked to the Russian government. Months later, Microsoft’s widely used email product Exchange was targeted by a cyberattack that was eventually linked to the Chinese government.

Bell’s success or failure at securing Microsoft’s customers from a growing array of bad actors is set to determine the growth of the company’s cyber business, analysts say, and help set the terms for how the tech industry can protect itself and continue to fuel global innovation.

Since Bell took over four months ago, he has tried to centralise all of Microsoft’s security efforts, previously siloed, under one organisation. Now 10,000 people report to him, and he has a budget to spend billions of dollars to build security products.

On Wednesday, Microsoft said it would be offering a simpler way to use its security products on Google’s cloud, a major competitor to its own Azure cloud. Microsoft had previously created a version of its security product compatible with Amazon’s cloud, so now its popular security software will be available at the three companies that account for more than 65 per cent of all cloud infrastructure services.

Bringing Microsoft’s security solutions to the clouds of different companies is crucial to solving cybersecurity issues, Bell says, because companies today are often dependent on too many small security products that defend only parts of their data.

Customers “get kind of a Frankenstein solution”, Bell says. “The problem is everywhere you glue things together, there are seams and those seams become places that people attack.”

Microsoft’s cybersecurity business has been consolidating its lead in the highly fragmented industry. Last month, the company said its cybersecurity business surpassed $US15bn in sales for the previous year, up 45 per cent from a year earlier.

“Their security surface is massive,” says Corey Quinn, chief cloud economist at the Duckbill Group, a cloud computing consulting service. “This stuff is hard. You only have to be wrong once, and everyone thinks you’re a fool.”

In addition to the SolarWinds and Exchange cyberattacks, the company in August had to repair a flaw in the Azure cloud – strategically Microsoft’s most-critical business – after a cybersecurity company found a bug that left customer data exposed. The Azure bug, which was discovered by the cybersecurity company Wiz, rattled some Microsoft customers because it showed how hackers could steal data by targeting one part of Microsoft’s cloud.

The growing prevalence of cybersecurity problems has hit close to home for Bell. Last month, his mother called him in desperate need of tech support. She had clicked on some offer and a stranger claiming to be fixing her computer had taken over her screen. “I said, ‘Mom, pull the plug’.”

The threats have created an opportunity for Microsoft. But the company finds itself in the awkward position of being the major target of cyberattacks while also increasingly profiting from the tools it sells customers to deal with these problems. “The old joke is, why pay for a filter from someone selling dirty water?” says Jefferies analyst Brent Thill.

Bell came to Microsoft after 23 years at Amazon, where he helped to build its cloud offering as it basically invented the cloud-services business, starting in 2006. He was at one time considered a contender to succeed Amazon Web Services chief Andy Jassy, who took over as chief executive from Jeff Bezos. Bell departed a few months after former AWS executive Adam Selipsky returned to the company from business software vendor Salesforce.com to take the job. Following weeks of negotiations between Microsoft and Amazon, Bell was able to start his new role in October.

Bell says he began talking to Microsoft because he had been thinking about the next big engineering challenge to tackle, and security became something he couldn’t get out of his head.

Microsoft was the best place to build better walls to block cybercriminals, Bell says, as no other company had the capital, vision or talent pool to face down the threat.

The Wall Street Journal