Meta’s free-speech shift made it clear to advertisers: ‘Brand safety’ is out of vogue

Social-media giant’s loosening of speech restrictions is unsettling advertisers, who say a decade of efforts to protect their reputations is at risk.

When Meta Platforms chief executive Mark Zuckerberg unveiled sweeping changes this month to loosen the company’s restrictions on speech, he talked about how the “legacy media have pushed to censor” content, how the recent election was a “cultural tipping point”, and how fact-checkers “destroyed more trust than they’ve created”.

Meta executives had a very different emphasis in a January 17 call with advertisers.

They focused on the steps brands could take to keep their ads from appearing near content they deemed out of bounds, whether it was misinformation or offensive speech. “In terms of brand safety, we are 100 per cent committed,” Meta ad executive Samantha Stetson told the advertisers, according to a recording.

That isn’t the way advertisers see it. Instead, they sense a profound vibe shift. For the better part of a decade, the dialogue between Meta and Madison Avenue has moved in one direction: The company pledged to do more and more to combat hate speech and misinformation on Facebook and Instagram, responding to grievances from brands and broader social and political pressures.

Now, a new cultural moment has arrived, punctuated by Donald Trump’s return to the White House, and Meta’s executives are carrying an unmistakably different message: Some things we used to remove will now be allowed. It will be up to users to help police the platforms through “Community Notes”, and advertisers will have to tune their settings to avoid anything objectionable, Meta says.

Advertisers have expressed concerns over the past few weeks – in meetings with Meta as well as with their own agency partners – that Meta’s tools might not be enough to stop ads from showing up near offensive content as the new content-moderation approach comes into effect, and that user feeds could become inundated with misinformation.

On the recent call, Meta’s vice-president of content policy, Monika Bickert, said Meta wanted to remove content that contributed to increased safety risks, but “allow people to talk about the news and the world around them and not be overly restrictive”.

One significant change: “Hate speech”, a term that she said “has different meanings to different people”, is being replaced by “hateful conduct”. Ms Bickert offered an example of the new order: The statement “women should not be allowed to serve in combat” would have been prohibited before, as a call to exclude people from a job based on their gender, but would be permitted now. That means an ad for, say, a car company could show up next to a post saying that, unless the marketer tunes its settings to exclude such a placement.

“We regularly meet with our partners to share information and hear feedback,” a Meta spokesman said. “Given that this call was specifically for advertisers, obviously it was focused on topics they care about, like the suite of brand-safety tools we’ve offered them for years.”

‘Brand safety’ backlash

Meta’s shift is a clear signal to companies that “brand safety” – the practice of ensuring that ads don’t appear near unsuitable or controversial content – is in retrenchment.

The practice gained traction during Mr Trump’s first term, when the juxtaposition of well-known brands alongside offensive content on social platforms sparked a backlash from advertisers and advocacy groups, such as when ads ran alongside YouTube videos promoting anti-Semitism and terrorism in 2017. The tech platforms ultimately granted all sorts of concessions to keep advertisers comfortable and their billions in spending flowing.

In the past few years, though, brand safety has turned from a topic for digital-marketing conferences into a political issue, advertising insiders say. Some Republicans and conservatives have openly accused ad agencies and brands of bias.

The issue boiled over last year when Elon Musk’s X filed a federal antitrust lawsuit against an advertising trade group and several big brands, including Mars and CVS Health, accusing the group of illegally boycotting the platform. X this month alerted the courts that it intended to add more defendants to the lawsuit.

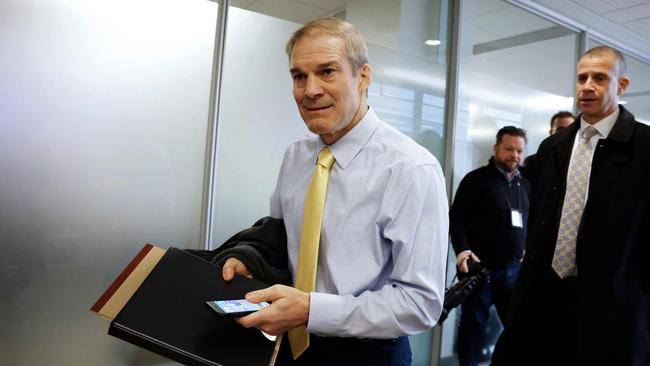

Mr Musk’s suit came after the House Judiciary Committee, chaired by Ohio Republican Jim Jordan, issued a detailed report in July that said the ad trade group and its members might have violated antitrust laws by withholding ad spending from social-media platforms and conservative media outlets.

Brand safety “has become politicised and it was never motivated by politics”, said Brad Jakeman, a former marketer at PepsiCo. The movement around brand safety happened because “we heard from our consumers that they felt uncomfortable with our brands being connected to content they found offensive”.

In December, days after advertising giant Omnicom agreed to acquire Interpublic, Mr Jordan launched a probe into the merger, seeking information on the companies’ ties to the trade group that Mr Musk sued. Among the requests made in Mr Jordan’s letter to Omnicom’s CEO: “all documents and communications related to so-called ‘brand safety’.”

Ad executives say they are wary of putting a target on their backs by speaking up about brand safety, and some agencies are now reluctant to send clients “point-of-view” memos on the topic when online controversies arise.

“Brand safety is under attack at a time when it’s needed more than ever before,” given the huge audiences for platforms such as Instagram and X and their more hands-off approach to monitoring posts, said Doug Rozen, former CEO of ad giant Dentsu’s media-buying unit in the US.

Shortly before the election, the Association of National Advertisers, a trade group that represents major advertisers such as Procter & Gamble, AT&T and General Motors, quietly ended a brand-safety effort called “Engage Responsibly”, partly to avoid scrutiny or litigation, according to sources. The website for the program, launched in 2020 to curb hate speech online, has been removed. The trade group declined to comment.

Despite misgivings about the new speech policy, advertisers are unlikely to shun Meta. They have grown dependent on its massive reach and ability to precisely target their ads, drawing on a trove of consumer data. Meta can afford some defections by blue-chip advertisers, as it is insulated by having a large base of small-business advertisers.

The company, the second-largest digital-ad player in the US behind Google with $US131.9bn in ad revenue in 2023, easily withstood a short boycott in 2020 over hate speech and misinformation by a host of companies including Dove parent Unilever, Verizon and Ford.

Safety controls

Meta’s changes include eliminating US-based fact-checkers and replacing them with Community Notes, a crowdsourced system that mirrors the approach Mr Musk introduced on X. The company plans to apply those notes to only “organic”, or unpaid posts, for now, but hasn’t ruled out applying them to paid ads eventually, according to an ad-agency memo viewed by the Journal.

Meta has said it would continue to use technology to detect and automatically remove certain content, but will tune its filters to target only what it deems high-severity offences such as racial slurs. For other objectionable material – such as calling gay or trans people mentally ill – it will rely on users to register complaints, and may respond by demoting a post rather than removing it.

In a note to top marketers and agency executives, Nicola Mendelsohn, the company’s head of global business, sought to reassure advertisers that Meta was still committed to providing brands with tools to ensure their ads run in safe places.

“We know how important it is to continue giving you and your teams more transparency and control over your brand suitability,” the email said.

Even if their ads don’t run directly alongside objectionable content, some advertisers are concerned that the changes could lead to an explosion of toxic or misleading posts on Meta’s platforms, making the general environment less suitable for ads. In addition to paid ads, many advertisers publish organic posts on Meta platforms.

Some are asking Meta to provide tools so those posts can also avoid controversial content.

The Wall Street Journal