Luigi Mangione’s dark descent from promising student to murder suspect

The Suspected UnitedHealthcare CEO killer seemed to vanish from view of family and friends six months ago, following a back injury and later surgery.

The notorious criminal suspect in an orange jumpsuit who shouted wildly about injustice outside a central Pennsylvania jail on Tuesday appeared to be light years removed from the smiling University of Pennsylvania graduate he was a few short years ago.

But Luigi Mangione’s transformation from promising student to accused murderer didn’t happen overnight. A look at his activities over the past few years shows that threads of his life — his work, his health, his ties to his family and his trust in the world at large — had been fraying in parallel.

Mangione’s life started to fracture about a year ago. But shortly after his 26th birthday last June, on the heels of a debilitating back injury and subsequent surgery, he had fallen off the grid altogether.

“Where in the world are you?” a close friend from Hawaii texted late that month. There was no response. A few months later, he was charged with murder in the predawn shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson outside a Midtown Manhattan hotel.

Interviews with associates, and Mangione’s own writings, suggest that the curious soul who had long been driven to explore the world around him began to instead direct his intellect inward in an almost torturous way.

A searching, insistent mind that had fuelled his academic success — he was his elite high school’s class valedictorian and earned honours at Penn — seemed to turn against him.

Mangione embarked on an obsessive quest to defeat back pain that he claimed was robbing him of a satisfying life. As he did so, he mused about loneliness, while gravitating toward “manosphere” intellectual figures such as Jordan Peterson, the Canadian academic who blames modern society for disempowering young men.

By the time of his arrest at a McDonald’s restaurant in Altoona, Pa., on Monday, Mangione’s journey appeared to have cut him off from his family, a wealthy and prominent Baltimore clan whose members were both high achievers and tightly knit.

In the ornate, high-ceilinged courtroom where he was arraigned Monday evening, Mangione glanced back to the gallery several times as if searching who might be there in his support. It appeared that no one was.

While Mangione had been out of contact with his family for months, he wasn’t entirely bereft. He was carrying $8000 in cash when he was arrested and appeared to have the resources to travel up and down the East Coast — albeit by bus.

He was on his own. One of his last posts on X last summer was a link to an AI-supported dating app. The slip-up that led to his face appearing in pictures released by the NYPD was related to an encounter with a friendly clerk at the hostel.

The unravelling of Mangione

As a teenager, Mangione appeared to be a prodigious talent from an established Baltimore family. His grandfather, Nicholas, a child of immigrants, grew up in the city’s Little Italy neighbourhood. His father died when he was 11. Nicholas went to work as a mason and eventually built a local real-estate empire that includes golf clubs and assisted-living facilities.

The family’s philanthropy wove through the city, from the Walters Art Museum, where relatives had the run of the place on “Mangione night,” to the Mangione Aquatic Center at Loyola University Maryland, where a roster of Mangiones starred on the soccer team and some later went pro.

Luigi, the scion, appeared poised to carry on the family tradition. He designed a mobile game app in high school, founded a video game programming club at Penn and completed his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in computer science in four years, with honours.

He was one of the thousands of college students whose senior years were truncated by the Covid pandemic. When the University of Pennsylvania shut down its campus in mid-March 2020 and sent students home indefinitely, Mangione’s life changed as well. At Penn, he led a busy life, hanging out with his Phi Kappa Psi fraternity brothers during the year and taking trips to hot spots such as Cabo San Lucas. Like everyone else, he suddenly went to virtual learning via laptop screen.

Because of the pandemic, the university’s school of engineering and applied science, known as Penn Engineering, held an online ceremony. When Mangione’s name was called, a smiling picture flashed up on a screen, accompanied by a gracious message to his parents: “I don’t tell you nearly enough how grateful I am for all you do for me. Thank you for all your sacrifices, and the lessons you’ve taught me.”

He entered the work world remotely, too, starting that November as a data engineer with TrueCar, an automotive digital marketplace company based in Santa Monica, Calif. Mangione had seemingly been a young man in a hurry, but his LinkedIn profile shows that he moved up the ranks methodically over the course of a year from Data Engineer I to Data Engineer II on the strength of his rebuilding a data pipeline to populate used vehicle loans.

By January 2022, Mangione was casting about for a new start. He appeared to find it in Hawaii, some 5000 miles away from the family home in Maryland.

He washed up at Surfbreak, a kind of upscale surfers’ collective in Honolulu, whose mostly young members, working remotely at jobs elsewhere, paid about $2000 a month in rent. During an entry interview, he portrayed Hawaii as a last-ditch attempt to repair his health, according to R.J. Martin, Surfbreak’s founder.

Mangione had written notes on Goodreads, an online book-review community, that he suffered from a condition known as spondylolisthesis, in which a vertebra slips out of place — either because of injury or as a condition from birth.

In Hawaii, he was hoping that with a change in nutrition and lifestyle he might avoid a potentially debilitating surgery, according to Martin, who found his new tenant upbeat and thoughtful.

Mangione could also be obsessive.

Among the materials on his account on Goodreads were copies of a dozen lined notebook pages in which he detailed his fitness plans in small handwriting and meticulous detail. “Goal,” he wrote. “Develop gym plan that I can start on morning of Friday 9/13.”

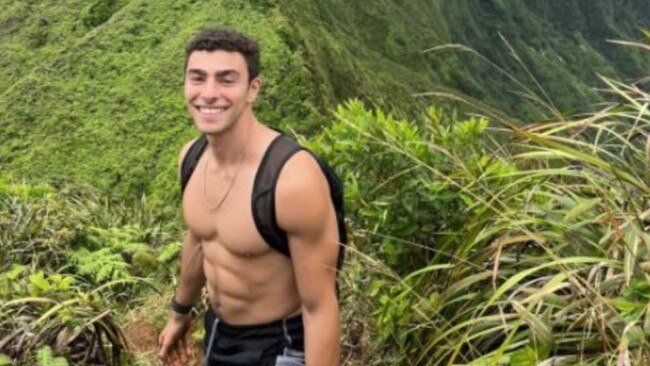

Over the ensuing pages, he recorded an exhaustive summary of a fitness book, breaking down diet and exercise repetitions. In pictures, he doesn’t appear to be a sickly patient. Rather, Mangione is sometimes seen shirtless, with his customary grin, flaunting Instagram-ready abs and chiselled biceps.

He employed a similarly driven and hyper-analytical approach to digesting the lessons of Angela Duckworth’s self-help book “Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance.”

That year, Mangione documented in his notebook the teachings from each of the book’s 13 chapters, and even reproduced some of its graphs and charts.

While at Surfbreak, Mangione also co-founded a book club that was in keeping with the collective’s community ethos. Some of the readings tended toward self-help, such as Tim Urban’s tome “What’s Our Problem?”

In an eerie coincidence, the club also read the statement of the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, which Mangione later praised on Goodreads.

But the Hawaii experiment didn’t last.

According to a Reddit post believed to have been written by Mangione, with a handle matching other posts attributed to him, he suffered a surfing accident the next year that had devastating consequences. “My back and hips locked up after the accident,” the user wrote, adding that “intermittent numbness has become constant” and “I’m terrified of the implications.”

Martin, Surfbreak’s founder, recalled that after a surfing outing, Mangione ended up incapacitated for days. In summer 2023, he returned to the mainland.

When Martin reached out to Mangione a few weeks later by text, Mangione sent back an X-ray image: He had had surgery.

It wasn’t clear what dealings he had with health insurance companies. By early this year, his social-media posts reflected a shift from optimism about the promise of technology to increasingly dark viewpoints. He had left his job at TrueCar and his roommates at Surfbreak. Some of his most meaningful interactions appeared to be on X, where he amplified heavyweights of the “manosphere” such as Peterson, podcaster and neuroscientist Andrew Huberman, and Tucker Carlson.

His posts and reposts show a young man considering topics such as the health benefits of psychedelic drugs, the potential downside of artificial intelligence, the impact of smartphone ubiquity on isolation and even population declines. It was a vastly different worldview than the one he expressed eight years before as a high school valedictorian who praised interconnectedness and common purpose.

Even as his life appeared to be going off course, he displayed stunning confidence in his own intellect. On Jan. 24, he posted a thread saying he used to get “bummed” in math class when learning theorems. “All the low-hanging fruit has been solved before I was born! If I was alive at the time of Pythagoras I could’ve easily derived the Pythagorean theorem and etched my place in history!” He said he felt lucky, though, that he now got to “simply download the knowledge of all who came before me, allowing me to stand on their shoulders and ponder new problems they never would’ve had access to.”

Meanwhile, Mangione was becoming hard to reach. Martin said he made plans to connect with his friend in February 2024. When March came and went, he texted: “Miss you brother. Hope you are mostly recovered. Let’s catch up soon.”

“Yea dude let’s catch up on the phone,” Mangione replied on April 15, according to Martin.

But they didn’t connect, and Mangione appears to have stopped communicating with at least some friends and family six months ago, around his 26th birthday. On May 20, Martin thought of his friend again and texted: “Yo! You awake?” Mangione didn’t answer, he said. A month later, on June 23, he texted him again. “Where in the world are you?” There was no response.

Mangione’s social-media posts also appeared to dry up in June and he was no longer replying to friends who tried to reach him through his X account. One pinged him, practically pleading with Mangione to respond to him about a prior commitment to participate in a fall wedding. Another friend wrote on Oct. 30 that his family was looking for him.

The San Francisco Chronicle reported that Mangione’s mother called the San Francisco Police Department on Nov. 18 to report her son missing, and said he hadn’t been heard from since July 1, when she said he had been working there. San Francisco police declined to confirm the report, and referred questions to the NYPD. After his arrest, New York police said that after college, Mangione had lived in San Francisco and that his last known address was in Honolulu.

In a Monday statement released by Nino Mangione, a cousin of Luigi’s and a Republican member of the Maryland house of delegates, the family said the news of Luigi’s arrest was shocking and devastating, and pleaded ignorance of any details: “We only know what we have read in the media.”

Upon his arrest, local police officers portrayed Mangione as contrite, even shaking at his table at the back of the McDonald’s.

Lt. Col. George Bivens of the Pennsylvania State Police said later that day that Mangione had gone from cooperative to far less so.

Clad in an orange jumpsuit Tuesday, as he was walked by two officers into the back of the Blair County Courthouse before his hearing, he shouted to onlookers.

“It’s completely unjust,” Mangione said, “and is an insult to the intelligence of the American people and their lived experience.”

Scott Calvert and Kris Maher contributed to this article.

The Wall Street Journal